I've Got A Mind To Ramble

Remembering Cliff Butler

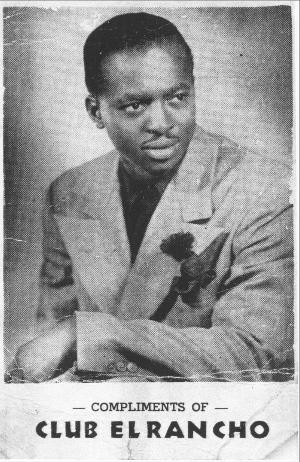

Most people in Louisville have never heard of Cliff Butler. Some of you who go back to the late Forties through the Seventies will remember him as the popular ballad and blues singer, disc jockey on WLOU and later a gospel preacher. The book, Louisville's Own, which gives capsule histories of local musicians, only briefly mentions Cliff Butler - with three short paragraphs - and lists him as recording two singles. Here is the rest of the story about this colorful entertainer, based on interviews with Butler's son, Lamont, Ben Ingram, who played bass in his band, and articles in the Louisville Defender.

Butler's mother died when he was very young and he never knew his father, so he was brought up by his Aunt Tobe in a very strict religious environment. Most of the family played musical instruments and they attended a holiness church, where there was speaking in tongues. Butler studied music at Jackson Junior High School and joined a jug band. He dropped out of high school to enter the Army Air Corps, where he got clerical and administrative training at Logan Field near Denver. When Butler was discharged from the service, he returned to Louisville to resume his musical career.

He organized his first band in the late Forties, playing at private parties and night clubs like the Silver Dollar, Club El Rancho and Club Neon. Lamont showed me an old, faded, red matchbook during our interview. It was from the Club Neon located at 18th and Maple. The silver lettering said "Cliff Butler, The Band with the Beat That's Really Reet. Swings His Way into Your Hearts." On the other side it read, "For Fun, Take Your Girl to the Club Neon." There were jam sessions at Club Neon every Sunday afternoon, which were also broadcast as the Midnight Ramble over WLOU. When an official at WLOU heard these remote broadcasts, he was impressed and offered Butler a job as a disc jockey.

The Cliff Butler Show ran Monday through Saturday in the afternoon. You could "meet Cliff on the street" at the corner of Walnut (Mohammed Ali) and 6th St. from 3:45 p.m. to 4 p.m. on Monday and Friday. Jockey Jack and Louisville Lou were other D. J.s at WLOU. Butler composed "Boogie with Lou" in tribute to her. Another bandleader and bass violinist, John Wickliff, composed "Jockey Jack Boogie." Butler was instrumental in getting the Johnny Wick's Swinging Ozarks to record that song for the United label in Chicago in 1952. Butler also recorded in Chicago on the States label during that time, cutting "Adam's Rib" and "Jealous Hearted." The following year he did "People Will Talk," "When You Love," and "T B Blues."

Butler's band included the great blind pianist Benny Holton and guitarist John Woods, plus the Doves, who sang backup vocals. Benny backed up Butler for over 25 years on keyboards, continuing to perform on Butler's gospel records into the Seventies. Brazzle Tobin, in a "Scouting Derbytown" for the Defender, quotes Bennie complimenting Wood's guitar style saying, "There are many local guitarists who can out-class John Woods in execution, but none possess the soul he displays."

Wood's best work can be heard on Butler's recordings of "Crying Blues" and "Gold Digging Baby" for the King label. Ben Ingram recalled those King sessions in Cincinnati, where arranger Henry Glover presided over the recordings of "Shame on You" and "I Dream Such Foolish Dreams." Cliff's earliest records were in 1948 on the Signature label with the Three Notes. They include "You Bring Happiness to Me," "She's Really Sweet to Me, "Please Don't Say We're Through" and "Benny's Boogie." The latter is a masterful solo instrumental by Benny where he shows his dexterity on the ivories. These four recordings were later reissued on the budget Guest Star LP that also featured Billy Eckstine and Arthur Prysock. Besides recording ballads and blues for Signature, States and King, Butler cut "Can't Get Her Off My Mind" and "Boogie With Lou" for Dot records, as well as "I Can't Believe" and "Everybody Needs Somebody" on the local Frantic label. He could shout like Roy Brown and he could croon like Jackie Wilson with a touch of gospel in all his vocals.

In another Defender article by Tobin, he tells of a Cliff Butler imitator working at Little Joe's Club in Chicago. A woman from Louisville was visiting the Windy City in 1953. When the MC announced the entertainer as Cliff Butler, she thought "Cliff has finally got the break he deserves." When she saw who was mugging in front of the microphone, she was disappointed and angry at this imposter. He was taking advantage of the reputation of the real Cliff Butler, whom she had seen perform two weeks earlier at the Chestnut St. Grill in Louisville. When Butler hard the story he said, "I'm glad to hear that this cat is upsetting Chicago with my name and song repertoire. The next thing for me to do is to strike out as a single and let the people hear and see the original."

Ben Ingram first met Butler when he was playing at a dance at Central High School. Ben switched from playing a sousaphone in the marching band to an upright bass in his senior year. He replaced Leslie Grimage, another Central student, on bass in 1949. Besides playing the local venues, Ben traveled with Butler all over Kentucky, Nashville and Cincinnati, doing one-nighters in armories. The band would travel together in a station wagon with a trailer in tow. Once when there was no room for his bass inside, they had to strap it down to the top of the car and it rained on the way home.

Ben recalled how the black social clubs in the Forties held formal dances once a year. These dances were often at the Brock Building at 9th St. and Magazine. The building was like a community center with an auditorium on the first floor. Butler's band frequently played these gigs and Lamont remembers helping his dad setup, but Butler would never let Lamont stay for the shows.

Lamont had many good memories of his father and mother, Flora, while growing up. They would picnic in Chickasaw Park and take tubs of refreshments to the Parkway Drive-in. Lamont's more vivid memories of his dad are from when he was starting his ministry. Butler suffered a mild heart attack at the height of his popularity as a singer and D.J. and he took it as an omen to come back to the church. After training in the ministry he returned to WLOU as an announcer for the Gospel Train program. When the station went under new management they wanted him to play rock music and Butler couldn't do that and quit.

From meetings in private homes to a storefront congregation at 30th and Greenwood, the Greater House of Truth gradually started. Since the small congregation couldn't support him, Butler had to scuffle around at several jobs, repairing televisions and selling insurance and autos. Butler continued to work on the growth of his church and it relocated to a converted house at 819 Humbler St. During the early Seventies Butler emerged as a spiritual leader and the congregation moved to its final location at 3701 Broadway. Besides serving as a place of worship, the building had a cafeteria, gymnasium, religious record store and recording studio under one roof. There was also a radio studio in the church, which broadcast the "Greater House of Truth" programs six days a week on WOBS-AM 1570. The slightly worn, classical brick and stone building is at the corner of 37th and Broadway and is currently occupied by the New Jerusalem Apostolic Church.

Butler produced many secular recordings on the Bluegrass label and later many gospel recordings on Randy's and Lu Sound labels. Enterprise was the backup vocal group Butler used on several of his gospel songs like "Everything is Alright." Besides Lamont, the singers included Butch Williams, Kenneth Martin and Albert Marshal.

In 1969 Butler started producing Christmas and Easter TV shows on Channel 41. These programs were variety shows featuring local R&B and gospel groups. Cliff would do interviews and close out with a sermon. Groups like the Religious Five and Archie Dell got their start on the show.

Mary Ann Fisher mentions in her unpublished biography that Butler was one of her favorite singers. When Mary Ann returned to Louisville following her days on the road with Ray Charles and with her solo career, she was shocked that there were so many changes, including that Butler had become a "Reverend." Butler wanted Mary Ann to sing "Misty Blue" on his Easter program. She told him "I don't play with God like that." She asked Butler to recommend a spiritual if he wanted her to participate, which he did. Butler kept a busy pace up until he died in 1981. Butler is quoted in an article by Clarence Matthews, the religious writer for the Courier Journal. "I want to work as hard for the Lord as I worked for the devil."

Butler's legacy is carried on by Lamont, who remembers his Dad singing in the shower and has continued his talent as a vocalist who sings gospel and songs from the Thirties to the present. Rusty Ends, Louisville's talented blues guitarist and songwriter, dedicated his CD to Butler "For the first live blues I ever heard." Everyone I talked to had fond memories of Butler as a congenial, fun type of guy with a mischievous nature. If any of you have some Cliff Butler stories, let me know at hyclem@worldnet.att.net.