social bookmarking tools:

|

|

| Available RSS Feeds |

|---|

- Top Picks - Top Picks |

- Today's Music - Today's Music |

- Editor's Blog - Editor's Blog

|

- Articles - Articles

|

Add Louisville Music News' RSS Feed to Your Yahoo!

|

Homefrontin' With John Gage

Author's Note: The header quotes for each section of the story come from transcripted audio segments from A Mighty Wind, the delightful mockumentary of the 1960s folk scene written by Christopher Guest and Eugene Levy.

"This is not an occult science. This is not one of those crazy, uh, systems of divination and astrology. That's stuff's hooey and you gotta have a screw loose to go in for that sort of thing."

IRS agents may be the most feared government professionals in the nation, but a retired one makes the loveliest rocking chairs.

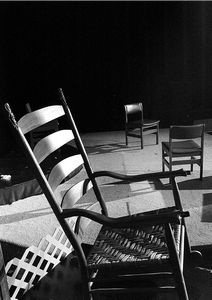

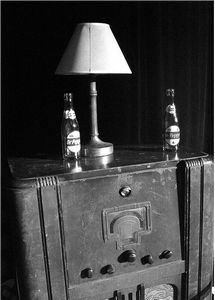

The chair, made by a retired IRS Agent in London, Kentucky, ironically-named Mike Angel, has a finish that glistens from the pair of spotlights that flood the stage where we sit with light and heat. The chair looks as if it has just been lifted off the craftsman's bench and set down after its final coat of shellac has dried. The ends of the arms are shaped to fit the grip of a human hand. Carved into the top of each back post on the chair is the face of a Native American, craggy with detailed lines cut deeply into the wood. Between us, a large RCA console radio from the 1930s, the glass rectangle of its dial now grayed out with age. At one time in one of the earlier decades of the last century, the radio had been the centerpiece of someone's living room and the rectangle glowed in pale orange with black numbers and hash marks and the tuning knob had to be turned with caliper precision to lock in a signal. It was one-way communication, single-channel sound with background hiss coming from a solitary speaker in the lower half of the cabinet, but every show the radio picked up had a captive audience. Some of those shows featured music from far away, with banjos, guitars, a thunky bass line and singers whose voices cut through the static like needles through cotton.

On top of the radio, two original Dr Pepper bottles (the shorter kind, with a flared bottom and the brand's red-and-white logo with the numbers 10, 2 and 4 positioned in a triangulation, the three times of the day which were the perfect time to drink one down, according to the brand's folklore) flank a slender desk lamp.

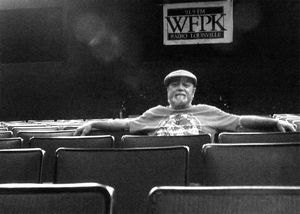

Welcome to the pulpit of Reverend John Gage's Church of Kentucky Homefront: the stage of the Kentucky Theater, where the "Kentucky Homefront" radio show is taped for later broadcast on WFPK.

Gage gazes toward the 200 empty seats in front of us. "One time one of my friends said, `I think "Homefront" is your church.' And that's certainly a loose definition, unless you want to have a broad definition of preaching. Because music is preaching a lot of times. Even if it's a ballad. It's still exploring something about human relationships. There's a spiritual power in that."

Gage's pulpit is on a riser, setting stage right. Along with the chairs and the radio is a battered lectern on which rests the printed script of the previous "Kentucky Homefront" show taping, which featured folk music veteran Jean Ritchie. At the front corner of the riser is a section of latticework between three posts about a foot high. Behind us, a heavy black curtain covers the theater's movie screen. The setting is a minimalist version of a home front porch (hence, one meaning of the show's name), a place that's familiar, welcoming, comfortable, safe. To some, a church is like that, too. And a church is also the base for evangelism.

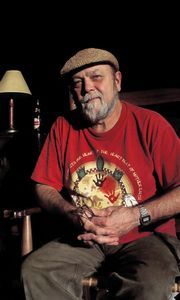

But Gage is a different kind of evangelist. You won't see him in an Italian suit, full slivery head of hair slicked back with enough wet schmutz that looks as if the Exxon Valdez ran aground on his skull, one manicured hand clutching a Bible, the other a cordless microphone, threads of sweat dripping from his face. Instead, this portly 60-year-old in battered trousers and a wicker cap, pepper-gray-and-white beard and a voice that is burred with age and experience stands on the stage each for each "Homefront" recording session and preaches the Gospel of the Arts.

"I want everybody to be much more evangelistic about the arts," he declared, "because the arts are powerful. And, hey, I was involved in music when I was a youth evangelist and the power of music was palpable. Every effective evangelist has that choir trained and when they reach that part in the sermon, they can cue that song. . . ."

He softly sings the opening line of "Just As I Am," the song that brought sinners in all congregations out of the comfort of their pews down to the altar rails, down to confront their sins and maybe even leave behind something that represented them: a pack of cigarettes, a tissue still damp with the tears of shame, a wadded-up dollar bill that was originally on its way to some bartender's cash drawer.

Reverend John Gage, ordained Baptist minister, former educator and school system administrator and co-founder and current Artistic Director of the Kentucky Theater Project, doesn't have an altar call anymore. He actually hasn't had one in several decades. The message he has now doesn't require him to bring sinners to the Lord, but while you can take the pastor out of the church, you can't take the church out of the pastor.

"I still know I have an affinity with that same thing," he said, "because I do have that sense of mission. Now my message is community, people living together in harmony, people respecting each other, people giving expression to the longings in their soul through the arts, through music, through plays, through singing.

"The arts. . .I think that's where God is for me."

Sitting and listening to Gage speak feels like a visit with a wise relative, or the old neighbor down the street. It feels as comfortable as a favorite pair of shoes. Ask one question and you'll get a sprawling tale in which you can find more than one answer. Some pay through their noses (and a few other body orifices, too) to hear a guru expound on the pertinent questions of life and living. Their stories are often too oblique and you have to work hard to find the answers. Sometimes you don't want that. Sometimes you want a solid story with no vague allegories. Lots of songs contain those kinds of stories and sometimes the only way to hear them is in a theater with others looking for the same thing. And it helps if the singer-storyteller is comfortable in his surroundings.

"I'm a performance junkie," he said, "so it feels like home to me.

And I was a member of the chess team. And whenever we would have chess tournaments, I had to wear a protective helmet. I had to wear a football helmet. Now, who knows what she was thinking? Maybe she thought that we might have fallen maybe and impaled our heads on a pointy bishop or something, I don't know."

Born and raised in Oklahoma City, John Gage began reaching to people first as a youth evangelist.

"I chose the career as a minister, actually, when I was 10 years old," he said. "By the time I got into high school, I was carrying my Bible every day. Most people wouldn't believe it because I'm not quite into it like that. I still have a sense of spiritually, but I'm not into that evangelistic outreach type of stuff."

Gage graduated from Oklahoma Baptist University in 1967, having majored in English and minored in philosophy, committed to becoming a full-time minister. The one place he needed to go to complete his training was the Southern Baptist Theological Seminary in Louisville. He arrived here after graduating from college, with a wife and his ambitions.

He brought something else: skill with music.

"I can remember singing for people from the time I was four or five years old," he said. "I started playing classical violin when I was in the third grade. I played, ironically, until the eighth grade, at which point orchestra class conflicted advanced algebra and I was really into math. So I opted for advanced algebra and stopped playing violin," he said with a chuckle.

But he didn't surrender all of his musical abilities in order to unlock the mysteries of factoring prime numbers and solving linear inequalities. He had learned music theory and choral conducting at church camp, took voice lessons, even sang in a couple of operas.

"The music was moving, but I never got on with opera much," he admitted. "But I was heavily classically oriented. For example, when The Beatles came along at first, I just looked askance at them. To me it was pop music and I wasn't into it. But I'll never forget when 1963 came and there was a huge hit from Peter, Paul and Mary called `Blowin' in the Wind.' And that blew me away. I was so ready for `Blowin' in the Wind' and the message that was there. I think my life changed direction then and I really began to listen.

"And, gradually, I even started liking The Beatles."

There is a proverb that goes "When the student is ready, the teacher arrives." For those whose lives are defined by music, there are those times when their minds are in a state where they hear a certain piece of music that transforms them. For jazz lovers, it might be the first time they hear Miles Davis's "So What" or John Coltrane's "A Love Supreme." For progressive rock fans, it is probably when Keith Emerson's synthesizer in "Lucky Man" rumbled and blasted through their headphones while they lay in darkened bedrooms that smelled like spilled bong water they tried to cover up by splashing Brut on it (hoping mom would never come in and take a real good whiff) and where velvety black light posters of flaming skulls and eagles wearing Native American headdress covered the walls.

For folk-music lovers, it is almost always the first time they hear a Dylan song.

"It just transported me," Gage said. "I was so ready for that. I didn't even know it until I heard the song and had such a huge response to it. It really resonated with my whole being. And it was then that I really began to broaden. I still love classical music to this day and I looked disdainfully on pop music when I was younger. But when it became Bob Dylan, The Beatles, Peter, Paul and Mary and the Mighty Wind folks," he added with a chuckle, "I was totally swept away with it.

"That's when I started getting more into pop music and that's when I started picking up the guitar and singing."

"We're very pleased to be having the folk people here tomorrow night. It's not something we usually do. This is, obviously, more of a classical venue. But it. . . it'll be a lot of fun. It's like having a carnival come to town, or something."

"Now here's the real question," Gage muses. "Is obscurity marketable?"

His answer: yes. The way to do it: a radio show, specifically "Kentucky Homefront," now in its second incarnation. The first one ran from 1984 through 1994, a respectable length of time for a locally-produced radio show that ended up with an audience that reached from Maine to Guam.

"Homefront" came about after Gage had been performing in Louisville for more than 15 years. "The original `Homefront' was done at an old Presbyterian Church at Sixth and Magnolia. It was really cool because it had wonderful ambiance, pretty good acoustics and it was like a miniature Ryman Auditorium because it had curved church pews and an old pipe organ and a stage that originally was the altar."

The program moved its production to Wyatt Hall on the Bellarmine University campus for awhile, then it settled into the First Unitarian Church. So even though Gage had left the active ministry ("I started seeing the dark side," he said, "seeing these men of the cloth who were disappointments to me as a young person."), he kept returning to church, if only as a place to perform because of built-in acoustic excellence in many of them. All the while, the national and international audience for "Kentucky Homefront" grew.

"We got a grant from BellSouth," he said, "and working with WFPL - in those days when they were part of the library - and Joe Vincenza, we bought satellite time. We put `Homefront' on the bird and at that time it was on 40 or 50 stations. We didn't have any way of knowing who was broadcasting it because it was just up there on the satellite. We asked people to let us know and some did. But then we would get calls from artists from Iowa, saying `How do we get on this show?' We asked, `How'd you know about it?' They said, `It's on the radio out here!'"

After a 10-year run, "Kentucky Homefront" went on a hiatus, one that became permanent when Gage had a massive heart attack in July, 1995.

"That shut everything down," he said.

More than a year later, the first steps toward a return of "Kentucky Homefront" occurred when an entrepreneur purchased the Kentucky Theater on Fourth Street, saving it from an appointment with a backhoe and a dump truck. Built in 1921, the theater became one of the many on Louisville's Fourth Street Theater Row, along with the Ohio next door, the Lowe's (later split into the United Artist and Penthouse theaters), the Mary Anderson and the Rialto. By the mid 1980s, the theater had become home to a multimedia presentation promoting Kentucky tourism. In 1986, its doors closed permanently. Ten years later, the city had slated it for demolition.

The entrepreneur who purchased it turned over ownership to Gage and Jeanette McDermott, both of whom then created the Kentucky Theater Project with the goal of developing a performance space. Since then it has been used to show special films, provide a stage for improvisational groups and as a venue for live music, including the refurbished "Kentucky Homefront."

But since "Homefront" was a live show with a history of radio play, could that happen again?

"It wasn't hard," Gage said, "but in order to put your show on, they have to take something off and there are stations that are looking for material. But if they take something off to put your show on, they're going to get some complaints and they don't like that."

Former WFPK Program Director Dan Reed and Public Radio Partnership President Gerry Weston provided Gage some advice on getting "Homefront" back on the air.

"You have to have a dance that you do with these people," Gage explained. "You have to be persistent without being a pestilence. And that means you have to walk that line, you have to understand the pressures that these people are under. They work hard and do the very best that can to make good decisions. You have to respect where these people are coming from. And be patient and try to keep your programming aligned with where the public is. Find something you have to offer. Find a niche."

Dan Reed gave Gage some great advice. He told Gage that if he wanted to do live performance radio, he would have to find that niche, the type of performance programming that no one else was doing. When Gage asked what that would be, Reed replied with Bluegrass, traditional country, stuff like that.

Gage replied, "You mean the music that's indigenous to Kentucky? The music that I've been a part of? No problem!"

"Kentucky Homefront" was reborn in February, 2001 with the recording of its return show. In June, 2002, Dan Reed ordered the first batch of shows for its regular time slot, Wednesday's at 8 p.m.

In addition, the music for the revitalized "Kentucky Homefront" would be more focused and not as eclectic. "We were much broader," Gage said, "and we were booking any act from Washington, D.C., from Chicago, from Iowa, from wherever. If we heard these people, we booked them. But now we are exclusively regional and local acts."

However, that can lead to some second-guessing. "You're booking acts that most people have not heard," Gage said, "so they have to trust that you're going to bring in good talent. And I think we do it. People come to these shows and they don't know who the hell it is. But they know that it will be pretty good, if not mind-blowing."

And that creates another challenge for Gage and "Kentucky Homefront." If you have a show featuring performers from one region of the country and you want other stations to broadcast it, can you market that kind of obscurity?

Gage's answer: yes.

"I think if people catch on," he said, "if you hang in there long enough, I think somebody in Spokane, or in Santa Fe, or in Atlanta, once they caught on to what this show is about would tune in because it's somebody they've never heard of. I'm placing bets on that"

"I feel ready for whatever the experience is that we will take with us after the show. I'm sure it will be an adventure. . .a voyage on this magnificent vessel. . ..into unchartered waters. What if we see sailfish jumping. . . .and flying across the magnificent orb of a setting sun?"

It is appropriate that the "Homefront" radio show is produced in the Kentucky Theater, namely because Gage's goal is to make the show a state-centric production, which will benefit Kentucky and the city from which it originates.

"I want Louisville to be the gateway to Kentucky," he explained. "I think it can be. But Louisville is relatively disconnected from the state and that's unfortunate because it is the big city and when you get out in the state, there's prejudice against Louisville. I'd like to erase all of that."

First, though, Gage needs to span the state and mine the talent that is inevitably there.

"There's Highway 23," he said, "that runs from just north of Ashland to just past Pikeville. You've got Dwight Yoakm, the Judd's, Loretta Lynn, Crystal Gale, Billy Ray Cyrus, Ricky Skaggs: huge names all from that area. In fact, in terms of the number of stars from a relatively small geographic area, it rivals, if not exceeds, any other place in the United States. And for every one of those, there are twenty no one's ever heard of. Maybe more. I see a hell of a lot going on. I don't see and end to it."

Part of the ambitious plans Gage has for "Homefront" is to record 26 shows for a year's worth of broadcasts: 20 shows recorded in the Kentucky Theater, the balance recorded on site in regions throughout the state, where there would be "Homefront" events featuring the area's craftspeople, storytellers, dancers, where recording of the radio show would only be a single attraction and where the other arts from the region would get a chance to grab the attention.

And Gage's plans don't stop there. "If I really wanted to do something significant for the Kentucky Theater, it would be to make `Homefront' a national show. That would give the theater a huge boost. It would give Louisville a huge boost. It would give Kentucky a huge boost. It reflects the cultural expressions and I think they are instinctively tied to regions."

Despite battling diabetes, respiratory disease and heart disease, John Gage is constantly active with "Kentucky Homefront," the Kentucky Theater Project and his own personal performance schedule. Ramping up the "Homefront" production by taking it out on the road and developing it into a nationally-broadcast program would spread him thin, but he already knows which one of his projects he'd pass on to someone else should that happen.

"The biggest challenge for me in this whole deal," he said, "is trying to make a living, so I have to stay diversified. The downside of that is I don't have enough time to do any one of those three right. Focusing on any one of those three would be enough. Well, I'm never gonna give up being a performer, so I can't let go of that. I'm not saying I'm getting out of the theater, but I think about what I would cut out if I found somebody crazy enough to do this work for the pay. Or once we found a way to put more financial stability into this enterprise, I would probably just rotate to the board of directors and not have a position here."

The theater's financial situation improved recently with a grant from Metro Louisville. Combined with sponsorship from Guitar Emporium and Winston and Company insurance brokers, the grant brings the project closer to its renovation and expansion goals. The theater also makes money on event admissions, concessions and they take a percentage of product sales from those who perform there. It all goes to sustain a base for Gage's dream of "Kentucky Homefront's" expansion into the state, to introduce people in one region to the crafts, music and customs of another and to introduce all of it to the rest of the nation. To make the largest altar call in the brief history of Arts Evangelism.

"I think there's a mission," Gage said. "And there's a lot to do."

More information is available at www.kytheater.org/homefront