social bookmarking tools:

|

|

| Available RSS Feeds |

|---|

- Top Picks - Top Picks |

- Today's Music - Today's Music |

- Editor's Blog - Editor's Blog

|

- Articles - Articles

|

Add Louisville Music News' RSS Feed to Your Yahoo!

|

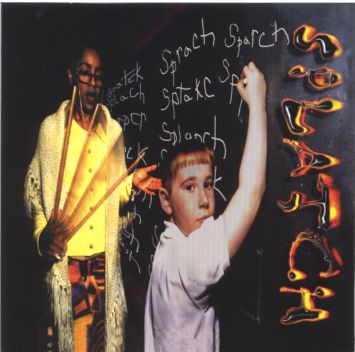

SPLATCH: AT THE MARGINS, IN YOUR FACE

By Tim Roberts

Pat McDaniel clutched the tall, dust-filmed trophy and held it up to me. "We got this at a club called the Deerhead in Evansville about a year ago," he said, grinning, "for being the LMFB."

We were in the basement workshop/mini-studio of the home of Pat and his brother Tony, a factory showroom-neat, split-level dwelling in Louisville's South End, a short drive from Iroquois Park. The trophy Pat held was a standard sporting goods store model: red and gold aluminum panels on white marble. On top of its center post was the gold-plated figure of a woman reared back to serve a volleyball. The golden numbers 19 and 87 flanked the center. The lettering on the plaque at its base was tarnished and had some kind of acronym with the date, but the acronym was not LMFB.

LMFB," I asked.

From over my shoulder Tony McDaniel said, "Loudest m****-f****- band."

Brothers Pat and Tony McDaniel are, respectively, the bassist and trumpeter of Splatch, Louisville's jazz-fusion-funk quintet with a reputation for being loud, in both their opinions and sound. After their gig at the Deerhead, the bartender or someone must have grabbed an old volleyball trophy - probably won by a team the bar had sponsored, its significance forgotten in the passing of a decade - and presented it to Splatch for being the LMFB. It now sits on a shelf over one of Pat's worktables where he makes bass guitars.

The Deerhead, Tony explained, features all kinds of music. The jazz performed there is mostly traditional, far from the grooves Splatch carves into the venues where they play. "They have some rock acts play there," Tony said. "We probably weren't the loudest band, but we were definitely the loudest jazz band they'd had."

Which may be a problem for Splatch. In Louisville, a city where almost all the jazz is traditional or be-bop covers of standards and played in just a few venues, from dim hotel bars to private corporate gigs, along with appearances by world-renowned talent, Splatch is an anomaly, disenfranchised from the rest of the jazz community, at the edge and looking over.

They wouldn't have it any other way.

The band consists of:

Tony and Pat McDaniel, a pair of brothers whose big-band musician father exposed them to jazz when they were small, both of whom have been playing professionally since their mid-teens.

Sam Gray, a drummer and entrepreneur, whose experience ranges from funk to hip-hop to fusion, who runs his own studio, Ramcat, where the recent debut CD (reviewed in the October issue of the LMN) was recorded.

And two Louisville music veterans: Pete Petersen, a keyboardist who has played with bands that span an encyclopedia of musical styles, and Earbie Johnson, a wise medicine-man percussionist who does more than strategically shake a maraca, who sees the band's potential to do great things.

Unlike the core of jazz performers in Louisville, the members of Splatch only have some to little-to-no formal musical education. Their training has come from experience in the business, on the road, in the clubs, and in the studio, and by listening to everything from Miles Davis (mostly later material like Bitches Brew), Parliament, the Ohio Players, and a smattering of little-known synth-and-metal guitar bands.

Their sound is aggressive, in your face, a bass-y jazz-funk that vibrates the enamel off your teeth. And they do play loudly. As their drummer Sam Gray said, "We're too loud for the jazz clubs but not loud enough for the rock ones."

I experienced that sound of jazz-funk power on October 17 at the Splatch CD release party in the Cafe at Barnes & Noble Booksellers. Normally the Friday night music in the cafe is light, ambient, folky, loud enough to call attention but still provide some background music for the people slurping Starbucks and lattes. That night Splatch became the blast furnace heart of the mild-mannered bookstore. Cafe workers couldn't hear customer orders. Booksellers working the floor couldn't hear the phones ringing. But interested customers stayed in the cafe or stood outside its periphery. The band's power cut through the store's woodgrain-and-marble old-library atmosphere. To put it in funk terminology, Splatch tore the roof off the sucka!

A Saturday night, early December 1997. A corner booth at the Rudyard Kipling. 100 Acre Wood, the LMN cover band for December, was playing in the back room. The small bar was crowded, a group of older people was enjoying a late dinner two tables in front of us. I was surrounded by Splatch, minus percussionist Earbie Johnson, who was dealing with the joys of moving into a new home.

Splatch. What is it? The guys contemplated the question for a few seconds.

To my left, Tony McDaniel answered it. He's in his mid thirties, slender, dark-eyed, black mustache and goatee tinged with a few gray hairs, wearing his Splatch cap with the bill turned backward. "It's really a noun, I guess. It's a place."

Pat, across from me - built like his brother but clean-shaven with blue eyes and a tight crew-cut - added, "It's an erogenous zone."

We each cackled in turn like a knot of schoolboys at the back of the classroom reacting to a racy wisecrack to the teacher. Sam Gray finishes the thought. "We're legends in our own erogenous zones."

We finished the laughter. Tony continued. "We'd talked about the name, and I didn't even think about it until later, but Splatch to me sounds like the colors of music, different shades. Splatch, to me, kinda has the connotation of an artist's term. . .the sound paint has when it hits the canvas. If you throw a lot of colors together, they're gonna intermingle."

But isn't "Splatch" the title of a track from Miles Davis's Tutu? And isn't the band's sound partially inspired by some of his later works?

All the band agreed. Pat said, "It was between 'Splatch' and 'Hey, Rudy'," another selection from Tutu.

That was just too off the wall," Tony replied.

So, Splatch. The name is succinct. Hard to spell. Kind of nasty. And it brings up further connotations: the sound made by water balloons dropped onto the principal's head by the school's bad seeds, a fresh scoop of vanilla ice cream hitting the middle of a dirty sidewalk, a pie in the face of Louisville's traditional jazz community.

They did exist as a jazz entity in Louisville before they were known as Splatch, sans Sam Gray and Pete Petersen. The Brothers McDaniel and guitarist Gary Crawford (who plays rhythm guitar on the debut CD) started out playing most of the same songs they do now. The trio advertised for a drummer. One day in early August 1995, Sam Gray saw the ad on the bulletin board at ear X-tacy. Gray, who had moved back to his native Louisville from Nashville, where he had exhausted himself by drumming with several different bands, had started Ramcat Studios. By that time he was probably ready for another gig. He called. They met. They talked. Another part of Splatch was added.

Not long after, Gary faded off but later returned to add his rhythm guitar to the debut CD. With Sam on drums, Splatch remained a trio. One night Pete Petersen stopped by a club where they were performing (either Butchertown Pub or Sparks - no one in the band seems to remember) and saw that an energy was there. Saw, as he said, "their head was into it." Not long after, he became the keyboardist. With the recent addition of Earbie Johnson, the band seems to have assembled itself from shared joys and visions. And a hard-a**ed contempt for complacency.

Louisville's a cheesy jazz town," Tony said that night at the Rudyard Kipling, "as far as it's a lounge-jazz town. If you're doing anything that's outside that realm, you're forced to these margins 'cause you don't conform. And I think not only our band but the Java Men are kind of marginalized, and Ron Hayden's band, to some degree, probably is, too."

The Java Men are Louisville's daring, experimental jazz trio, able to slide between the avant-garde and standards played their own way, while the Ron Hayden group is a premiere fusion band, whose most recent work was on Jak Son Renfro's jazz opera DisArmageddon, for which Ron wrote and arranged the music. They are similar to Splatch in that they, as groups, do not perform what Tony called lounge jazz, those be-bop or straight-ahead versions of standards, often played in low-ceilinged rooms with dim lights. Even if is interpreted differently by individual performers, a standard is still a standard. Put another way: Rogers and Hart's "You Are Too Beautiful" is still the same song, regardless of the interpretation.

Where the similarities end between Splatch and the others is band-member education. "A lot of those guys in those bands went to school in town," Tony continued. "I didn't. I was playing on the road. The music school thing was already in the upbringing that Pat and I had. We had a personal music school."

Whether we wanted to or not," Pat said.

Their father, Preston McDaniel, was a full-time barber and part-time musician, and vice-versa, who played alto sax and trumpet under a number of big band leaders: Jimmie Lunceford, Billy Vaughan, George Berry. The McDaniels have a chestful of their father's charts, all organized by part (first trumpet, first alto, etc.) in large, brown accordion file folders, each piece numbered sequentially. The band had numbers on the music so that the band leader didn't have to call out a full title during a performance.

Tony and I leafed through them gently one evening when I visited his and Pat's home. All the pieces were classics: "Laura," "Sophisticated Lady," "Cherry Pink and Apple Blossom White," "The High and the Mighty," "Ruby." Both Tony and Pat played trumpet when they were small. Their father taught them the tunes from his folders, and they performed father and sons trios: Tony on first trumpet, Pat on second, and Dad on first also sax.

Tony shook his head as we continued to sort through the stack of tunes. "I got so tired of readin' music. That's kinda anti-jazz in some respect." He chuckled.

Pete Petersen is the other member with a bit of jazz education, who started playing music in his teens. "I started playing the drums because my brother played in a band. But then my parents took them away from me," he told me with understatement. "Then I tried saxophone, and my dad kept complaining, referring to [my playing] as like living with a cow with an abscessed tooth. Then my dad bought a piano, so that was tolerable."

Pete taught himself how to play by copying guitar solos from Beach Boys songs and making up his own chords. He then moved to copying blues scales and began composing. "I didn't know what I was doing," he said. When he was 19 he met with jazz educator Jamey Aebersold, who taught him music theory, transcription, scales, and exposed him to jazz keyboard greats like Herbie Hancock and McCoy Tyner.

Now 45, Pete is the oldest member of Splatch, and brings with him keyboard experience gained from playing with numerous local bands: Crisis (where he played with Earbie Johnson), Serious Circus, The Shufflin' Granddads, and a number of lounge bands. One weekend in 1977, he and each of his bandmates made about $1,500 in the bar of the old Stouffer's Hotel (now a Holiday Inn) on Broadway by playing "Lucille" for a grateful drunk patron, who kept feeding them $20.00 apiece (later jacked up to $50.00) to play it repeatedly. The band was fired after the second night, but not because of the continual performance of "Lucille." Some blues singer from another club was using a microphone to imitate a consensual adult act. That was when the manager stepped into the lounge.

Pete's arranging skills also helped him during a stint in the Army, but not to its benefit. One night before a parade, he and a friend sneaked into the band room and re-arranged the music so that all parts would be a half-step off from one another. The next day at the parade, the band sounded terrible. Pete never confessed to the prank, but would always be assigned crappy detail duties. And he never rose beyond the rank of Private.

When you see Pete perform, you see someone with a relaxed focus, an immeasurable expertise. His head bends low, his shaggy dark-blonde hair hangs past his face, his fingers zip and leap across both levels of his Yamaha DX-7 keyboard like ballet dancers on fast-forward. And you can tell other members of Splatch are in that space as well: Tony, when he's not playing, bops his head up and down and jerks his body to the beat; Pat, his bass resting on outthrust hips, bobs gently; Earbie looks toward the band, seeking cues no one else hears, then comes right in with a targeted slapping of his congas; Sam gazes up and off to the left, relaxed, keeps the pace perfect.

Sam Gray apparently loves the microphone. During a performance, the tall, skinny young man with low-lidded eyes and long, crimped red hair talks with the audience, introduces the selections, subtly invites the audience to buy a CD or Splatch baseball cap. He sat in front of my tape recorder during the discussion at the Rudyard Kipling and frequently injected his comments. It's not because he likes to be heard. He likes to talk. Especially about music.

He started playing drums around age nine. "My parents were never very musical, so it was something that I had to discover by myself. I just decided one day the drums looked fun. A friend of mine had an old, beat-up set in his basement, so we started messing around with it one day. I instantly took a liking to it and was able to figure it out fast. It was mostly just a hobby for me until after high school. After that, I started focusing a lot more on it"

While attending school in Nashville, Sam played with a number of sign bands: Self, the hip-hop groups Me-5-Me and Count Bass D. "I was always in three or four bands at a time," he said. His interest in jazz came during his later high school years when he began listening to the Mahavishnu Orchestra, Jeff Beck, and drummers like Billy Cobleman and Michael Walden. Those bands led him to listen to works from Miles Davis and John Coltrane.

From all that listening and influence, Sam can easily fluctuate among and between styles within a piece. At the Barnes & Noble CD release party performance, Splatch ended the show with "Slide," a little-known tune from a band called Slave. Halfway through it, the tempo and style switched from funk to be-bop, Sam pulling the band along with tight cymbal rides and a sporadic tap on the snare. He finished that section with a long solo, then with a loud crack on the snare, snapped them back into funk.

Sam gets to hear plenty of local music at his Ramcat Studios, where the Splatch CD was recorded. For their next planned recording, though, Sam wants to get out of engineering and focus more on playing. "Engineering takes so much of my focus off playing," he said. "I'd really like to come in as just a player. That was one luxury I did not have when recording the first CD."

As Splatch prepares for recording its next release, the band is experimenting with their sound, tweaking it, gently varying from their arrangements. The first part of making those changes was adding a percussionist: Earbie Johnson.

Earbie was intense the night he and I talked. "Tired and angry," as he put it. The band was preparing its sometimes-once-a-month Saturday night gig at O'Shea's on Bardstown Road. We sat in a booth close to the bandstand. The 44-year-old Earbie chain-smoked, sipped dark beer, and praised the band.

They've got promise," he said, punctuating each word with a finger pointing toward the stage, "with or without me."

Earbie has 25 years in the business, having played in cities across the US and Canada, and in all kinds of styles, from jazz to reggae to Irish folk music. Splatch is the first full band Earbie's worked with in 10 years, which has, he says, "been a hell of an adjustment." Locally, he has performed with Crisis (q.v.) and worked with Love Jones. His last gig was with Serpent Wisdom. He also works with the Rajah Percussion Ensemble, which encourages children to play percussion instruments and develop self-esteem.

It has worked for Earbie. Twenty-five years of percussion has instilled in him a selfless wisdom. And a bit of hedonism, too. "I don't want accolades," he told me. "I just want to have a good time."

Band experience alone has not been the only element to define his style. He further developed it by playing to recited poetry, which taught him how to compliment a statement. I studied him at the performance that night. He played as if the rest of the band was reciting poetry - at one time maintaining the counter-rhythm, speeding and slowing when the mood was right, then throwing in arrhythmic syncopated slaps of the conga.

He describes his work with Splatch as a part of his journey. "I'm gonna be a better person going through this journey. And whatever this turns out to be, will be." He further described himself as an idealist, but his opinions about the band seem to come more from a quarter-century's work in the music industry. "Splatch is a different kind of groove," he said. "They've got a young spirit. They have the understanding.

Believe me. . .the music industry will hear from Splatch."

So how will that be done?

After the first of the year," said Tony, "we're really gonna push to try to get out of town."

So why leave?

He continued. "In all actuality, we wish there were more venues for us to play in town. Everybody is from here. [It's hard when] you're a non-recognized entity in your own town."

Sam jumped in with the most recent example of a local band gone big time - Days of the New, the power-acoustic quartet whose "Touch, Peel, and Stand" hit the top of Billboard's Rock/Mainstream Rock Tracks about a month ago, who have racked up a quarter million of CD sales, and even had an appearance on David Letterman. In Louisville, three people showed up at one of their performances at the Twice-Told Coffee House. On the final day of the Kentucky State Fair last August, they opened for The Smithereens, where about fifty people crowded into one section in front of the stage to hear them.

People in this city gladly pay five dollars to go hear a cover band at their favorite watering hole, but won't shell out a single dollar or two to hear original music played by local professional talent. "We're not the only band in that situation," Tony said. "The clubs don't seem to want to pay very much for any band.

Unless some things fundamentally change, as far as the club scene, we have to leave here. And then when you leave, make some money, get some notoriety, all these people then want to know why you're not playing in town."

A couple of major labels - including MCA-Impulse, one of the long-standing pinnacles of jazz recording - are interested in the debut CD. Major labels want to see that a band can play gigs besides in its hometown, that it is able to tour and support. However, touring support comes with a major label deal. It's a Catch-22 for the members of Splatch, who are shopping for an agent to get them out of Louisville.

Yet the band's youthful spirit, as Earbie calls it, is sunk into their bones. That itch to move, musically and professionally. To stay out on those margins and push them even wider.

We're ready to go," Pat said.