social bookmarking tools:

|

|

| Available RSS Feeds |

|---|

- Top Picks - Top Picks |

- Today's Music - Today's Music |

- Editor's Blog - Editor's Blog

|

- Articles - Articles

|

Add Louisville Music News' RSS Feed to Your Yahoo!

|

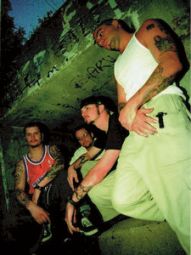

FINDING FLAW

By Tim Roberts

WARNING: This story is in two parts. The first part opens with an embellished rumor. The second part doesn't. To avoid confusion, read.

The rumor is highly tarantinian (tar'un'tin'ee'un - adj. Involving brutal acts of violence performed by the disenfranchised and/or members of the criminal underclass, with imagery driven by iconic elements of popular culture; from Quentin Tarantino, actor, producer, screenwriter and director, mid- to late-1990s.). In one, an acid-metal hip-hop quartet rumbles around town in a Dodge Ram van. The exterior is blue with dots of rust, tar and flicks of mud. Flaw is spelled out in white tape on both sides. It's either the band's name or how the world has judged them. In the rumor, they juice up from late nights laying out their sound, searing with an aircraft-carrier deck potency, in clubs jammed to the ductwork with sweaty tattooed and pierced bodies. Show over, they scurry to shove their equipment into the van, each man primed to the enamel of his teeth with an adrenaline-testosterone-beer cocktail. On the road, tires squealing, the van zipping between lanes, beers are sucked down faster than the bottles are popped open. Two pedestrians try to cross against traffic. Brakes slam. The van's tires screech on pavement. An arm coated in viney tattoos extends a 9mm out of the passenger window. Five shots later, the van roars away in an odor of burning rubber and engine oil. Two screaming men on the street bleed from their legs.

"I've heard a million rumors about us floating around town," said Flaw drummer Ivan Arnold.

"And we're not shooting people," emphatically added bassist Ryan Juhrs.

"Some people think we're a gang or something," said lead vocalist Chris Volz. "That is definitely not true," he added with a small smile, "None of us is a jerk."

"We just have some flamboyant . . . friends," said guitarist Jason Daunt.

With Flaw's image and sound combined, tracking the source of rumors becomes easy. The flesh-stripped rawness of their music, the anger in the lyrics, venues packed skin-to-skin with thrashing bodies - it's easy to see how the intensity could slip over into violence. People battering each other in a mosh pit can devolve, through unleashed oral reports from one fan to another, into a tarantinian myth of band as armed gang.

"Somebody will say one thing," Chris said, explaining the rumors, "then it gets to another. It's just like game of telephone. By the time it gets to the last person, it's a completely different story."

Flaw is in the music subgenre called metallic hip-hop, that spot where edgy, loud chords and low-register bass are arc-welded to rap lyrics. Flaw's contribution includes melodies that have the tonal quality of a Vedic chant. It's an unsettling sound that, just like the earliest rock-and-roll, threatens order, dredges the primordial parts of the brain for the ugly shadows crammed into hiding, makes the older folks uncomfortable. But instead of merely shaking its hips at the status quo, Flaw screams in its face. It's a sound made for the mosh pit, popular with late adolescents and early twenty-somethings, while also the current target of moral mercenaries still looking for an external demon to blame for the Columbine High School shootings in Littleton, Colorado.

"It's sort of funny," Ivan said, his voice in measured anger, responding to a question about the criticism of their style of music and how it was a favorite of the two boys who shot up Columbine. "Now that white kids are shooting each other, everybody's getting angry about it. Black kids have been doing that to each other for, what, twenty years? It [makes us] as easy scapegoat for crappy parenting. Those kids had pipe bombs in the house. They'd go out on weekends buying assault weapons. But it's our fault."

Individually, the members of Flaw are direct but far from violent: Jason is an honors graduate of the University of Louisville with a degree in psychology; Ryan is a former Marine; Ivan is the only married member of Flaw, demonstrating the depth of his commitment by his tattooed wedding band; Chris, the lyricist, is keeping the message real, unafraid of staring down his own demons, using his work to scatter them like milkweed hard wind.

"All our lyrics are directly related to something that's happened in my life," Chris said, "something I've seen, or something our generation has experienced, ranging from problems with parents to global issues. They're reality-based."

The reality in the lyrics extends to the realistic view the band has of what it takes to be working musicians. They are ambitious, highly professional, even charitable. Last year, they performed at the Hardcore for Kids show at The Brewery, a benefit to raise money for the WHAS Crusade for Children. Members from Flaw and the other performing bands presented the $300.00 proceeds on the air during the Crusade telecast. An impending trip to Los Angeles prevented them from being part of this year's show.

Flaw is also a band that does not overlook the minor details that keep a group of professionals responsible for their own direction. That includes such gnatty details as, say, having legal representation. For that, Flaw has obtained the big-gun services of Davis and Shapiro artists reps in New York. The Davis portion of the firm is named Fred, son of Arista Records founder Clive Davis.

The band has proven their ambition by papering the telephone poles of Bardstown Road (already layered in rusty staples) with flyers announcing a show. They also produced and distributed their debut CD and took it into stores, along with their other promotional items: T-shirts, lunchboxes, and Flaw Action Figures (each sold separately).

They are entrepreneurs, ready to take risks and expect success.

"We've always had that do it ourselves attitude from the beginning," Ivan said. "We said, `let's not sit around and wait for these [music label] guys to come to our door begging us to be their latest flash in the pan.'"

"We independently sold a thousand albums by ourselves," Chris bragged. "We probably drop off about 20 CDs a week to ear X-tacy."

Ivan continued. "I think that's a sign of encouragement for other bands. I hear a lot of `we can't do it, we don't have the money, no one's interested.' Too many bands limit themselves because they expect to fail."

"All you need is a credit card," said Chris. "Our whole American system is based on credit-"

Ryan interrupted. "And if you can't do it any other way, you can always sell your equipment."

The band laughed uneasily. Then Jason added, "You've got to take a chance. If you're not willing to risk everything, you're wasting your time."

The debut self-titled CD Flaw has been distributing to record stores around town and selling at their shows is a marvel of economy. It was recorded, mixed and produced in Louisville by Flaw and Chris Casetta at Canyon Productions, with equipment from Musician's Friend, a mail-, Internet-, toll-free-order music shop. Recording and mixing took only three days ("because we practice a lot," Ivan said). Every track was snagged by at least the third take. Work with Casetta was easy, since, according to the band, he strives to help a band get the sound they want.

The CD's packaging is almost Amish in its simplicity: a disc envelope of heavy, slick paper stock with the song list and production credits printed on a two-toned mailing label. Inside, however, is a sound that could melt chrome.

Flaw's CD was one of 18 local band releases David Gilbert bought during a shopping trip to ear X-tacy. That purchase led to Flaw's three-album contract with Mercury/Island/Def Jam Records. - Continued in "Losing Flaw?" on Page 5

LOSING FLAW?

By Tim Roberts

YOUR MOTHER SHOULD KNOW: The first part of this story begins on the previous page. Finish reading it first. And please keep track of these things.

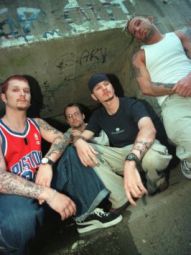

May 22 - It's a cool Saturday evening, the final night of business for P.J.'s Pub on Taylor Boulevard. About a half a mile north of Iroquois Park, the pub sits back from the street, fronted by a gravel lot. It was once the site of a succession of strip joints years ago. Its last version was The Kitten House. Whatever the name, the gravel lot was always full of motorcycles, a dare to many of the adolescent south-end boys who attended nearby Iroquois, Doss, and DeSales High Schools: see how many bikes you could pelt with eggs before you were chased down and got your butt handed to you.

A steep flight of concrete steps runs against the front of the building. Inside, the ceiling is low, the wooden floor scuffed and filmed over with a softness from too many spilled beers. A low stage rose in the left corner. Between it and a speaker stack, a jumble of drum kits, amps, guitar cases, and pedals, barricaded only by a yellow strip of DO NOT ENTER tape fastened to the walls and wrapped around a pole next to the stage.

The gravel parking lot was slowly filling with young people - lots of buzzcuts, tattoos and body piercings - there for the ritual closing ceremony of P.J.'s, preparing it for its transmigration into a liquor store. Providing the ceremony's incantations were Killcycle, Faceplant, Engrind and Flaw.

Flaw's members nervously wandered the parking lot. Family support was there. Sharon and Chuck Daunt, parents of guitarist Jason Daunt, arrived from their home in Florence, Kentucky. Lisa Arnold, wife of drummer Ivan, was there.

The stage was a first-, only-, and last-time part of P.J.'s interior. Normally Flaw would just set up their equipment in the corner to do a show, but it was necessary this evening. Their manager, David Gilbert, was bringing a representative of Mercury/Island/Def Jam Records to hear the band. A record deal was scratching at the rear door of Flaw's blue van.

After listening to recordings from 18 Louisville-area acts, which he purchased during a visit to ear X-tacy, Gilbert, of the L.A-based artist management firm called Revolver (which also manages Everclear), chose Flaw to approach for a management deal. That one CD, produced fast, tight, loaded with metal pyrotechnics and packaged like a demo for cheap software that arrives in the mail, became The Little White Envelope That Could.

Sets from each band were short, loaded with thrashing metal. Heat from the two emerald spots on stage and the solid collection of bodies sucked all air from the center of the room. The club was almost emptied between sets as most of the audience fled out the front and back doors, starved for cool air. Flaw's setup threw a circuit breaker minutes before they were to start, ratcheting the tension for them. Six songs later, the four of them were bathed in sweat like prizefighters after 15 hard rounds. Against the wall, arms crossed and as motionless as if waiting for a dental appointment, sat David Gilbert and the rep from Mercury.

The combination of sound, performance, professionalism won Flaw a three-record deal with Mercury/Island/Def Jam five days later on May 27.

Gilbert chose to approach Flaw because, as Ivan put it, "We just have a more marketable sound. With the success of other bands in the same sort of genre - like Korn, Limp Bizkit, the Def Tones - getting a lot of radio play, I think it's what set us apart from the other bands he listened to. But we didn't plan it that way. We just came together and made a band."

Flaw had been consistently rehearsing, promoting, and constantly performing around Louisville to packed venues, sweating, screaming, releasing their white-hot vibe to the city. They crammed three days of recording onto a CD and shopped it around themselves.

Now, after signing the deal with Mercury, the hard work begins.

"It has to be treated like a job," said Jason. "It may be more fun than going out and working nine-to-five, but it's just as much work and you need the same work ethic.

"But getting a management or record deal is only part of it," Ivan said. "Most of the bands that get record deals are nowhere now. It's not like they're has-beens - they're never-weres. They got big heads and stopped working."

According to Chris, a band's collective head also shouldn't get so big that it crowds out the fans. "Some people think that as a band your job is to go, play the show and that's it. But it's not. Hanging out and talking to the people who pay to come see you is all part of it. You want them to want to come back. It's about making the crowd feel they are part of it. People will never feel part of the music if you separate yourself from them."

"I hope we never get to the point," Ivan said, "where it feels like there's a wall between us and the people who listen to us."

"I think to an extent it has to happen," Jason added. "There's a point where you can't keep up with 20,000 people calling you. You wouldn't have time to play your music or write your music."

Flaw was singled out of eighteen local acts to have that shot at getting a larger fan base. In baseball, moving from the minors to the majors is called going to The Show. You leave behind a lot of envious and more-than-envious colleagues.

"I hope the animosity between bands [in Louisville] comes down a little," Chris said. "There's a lot of competition to the point where it becomes negative. There's a lot of backstabbing, which we're not a part of. We're not out to make as much money as the next band here in town, or to get a better spot. If the music industry in this town comes together, it will bring recognition."

Ivan concurred. "There's a lot of talent and potential here. I hope bands that come out of this town just don't abandon it. I hope they try to focus on the potential here."

The other major rumor about Flaw (alongside the band-as-armed-gang mentioned in the first part) is that, once they sign to a label, they will rip themselves from Louisville and transplant to Los Angeles.

Like the exaggerated tarantinian myth described in the first part, it isn't true.

There will be some trips to the coast. There are plans to record again. There is some talk of touring with the likes of Rob Zombie, but nothing solid.

One thing is, though: Flaw's dedication to the town where they formed. Each member grateful to P.J.'s, the Toy Tiger, and their fans. Los Angeles and The Big Show may lie ahead, but . . .

"We'll still be a Louisville band," Jason said with reassurance.