social bookmarking tools:

|

|

| Available RSS Feeds |

|---|

- Top Picks - Top Picks |

- Today's Music - Today's Music |

- Editor's Blog - Editor's Blog

|

- Articles - Articles

|

Add Louisville Music News' RSS Feed to Your Yahoo!

|

The Legend of a Wizard and his Hundred Proof Blues

A Tuesday night in January, and it's so cold it feels like my breath might crack into icicles as I made my way across the street into the warm, red atmosphere of the Twice Told Coffeehouse. A motley assortment of characters have assembled, as usual: a blonde girl in black announcing a free show from a band traveling through Louisville from Chicago; a bearded man in blue sitting alone, sipping coffee and watching the other customers; an intense, dark-haired boy intent on a book, perhaps in the process of discovering Jack Kerouac. The club's owner beats a slow rhythm on a table to the sound of an elderly black man in a suit jacket and stocking cap singing the blues.

At the front table in the window sit four men, talking. Three of the men look like baby boomers discussing their glory days over coffee, but one bears a striking resemblance to my idea of a wizard traveling incognito among us humans: His face is thin and angled, topped by a wild mass of pale white and gold hair. He wears gold round-rimmed glasses, a sliver of a white goatee, and he is dressed in a burgundy overcoat and the nattiest pair of patent leather-and-leopard-skin-shoes I've ever seen. He looks, as all wizards should, like he knows far more than he's telling, and he's seen far more than he knows. The men notice me eyeing them uncertainly.

"Are you looking for Lamont Gillespie?" one of the men asks, a friendly-looking guy in a gold short-sleeved shirt.

"Yes," I answered, because it was true. I was at Twice Told on a cold Tuesday night to interview the man who some had told me was the best blues harp player in town.

"Well," said the wizard, all angles and a grin, "you've found him!"

Indeed, I had.

It's always impossible to tell whether or not you're talking to a music legend in the making, since so much of the story's unwritten and history hasn't yet been able to obscure a life's boring parts in tarnish while adding a rosy glow to the good stuff. But still, there are a few telltale signs.

First, you have to be the sort of person who gets a sound into their very bloodstream and devotes him or herself to it like a pilgrim in search of Mecca. Gillespie discovered the blues by chance as a young kid growing up in Louisville.

"I was introduced to the blues by my brother, who would tune in to WLAC out of Nashville late at night, which was the only time we could get it in Louisville. I heard Muddy Waters, Howlin' Wolf...I didn't know what I was hearing then, but I sure am grateful my brother was into the blues when I was rowing up instead of Pat Boone or something," said Gillespie.

A Louisville native, Gillespie's parent separated while he was still quite young. His mother moved to southern Indiana while his father moved back to his native home in Greasy Creek, KY. Towards the end of high school, Gillespie moved back to Louisville and finished high school here.

Soon after high school in the early 1970s, Gillespie met blues player Jimmy Masterson, who was just forming, the Masterson Blues Band. Gillespie became the band's manager and would introduce them before their performances.

"I realized I liked the feeling of being onstage," he remembered.

The only problem was, Gillespie couldn't play an instrument. Masterson suggested Gillespie try the harmonica.

"My family grew up playing bluegrass, and I figured the ability to play had to be in my blood somewhere," said Gillespie. He headed to the S.E. Davis Pawn Shop and picked up a blues harp.

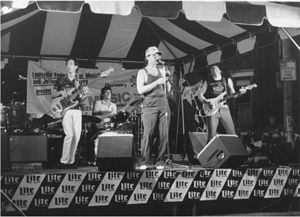

Soon, Masterson's band was letting him sit in on sessions. "Jimmy told me years later that it showed we were really good friends when he'd let me play with the band because I was really terrible at first," laughed Gillespie. But, like all good legends-in-the-making, Gillespie kept playing. He realized he didn't like the standard blues harp as much as the marine band harmonica, switched to that and gradually began to develop a style that made him stand out as a blues player. Soon, he was ready to form his own band and joined with Rick Mason and Bruce Lively to form the Stray Cat Band, a successful blues and rhythm band that played regionally from Louisville to Key West, Florida to Indianapolis and back again.

"We were a full-time working band," he remembered, "we had a good run for seven or eight years. One year we worked 200 days out of 365, and we'd travel around in this old school bus."

While the band never signed to any label or released any major recordings, they did make a good living - a feat in and of itself, as many Louisville bands will attest. The band gradually disbanded in the early 1980s, and Gillespie moved to Louisiana to try his blues chops out there.

Though the fame and fortune he might have wanted never found him in Louisiana, love did. Gillespie married and had two sons and eventually found his way back to Louisville again. Now a husband and father, Gillespie still felt the pull of the blues, which leads us to the second predictor of music legend status: continuing to play even after it gets hard.

"The blues still do to me what they did the first time I heard them - I don't know what it is," he said, `soul, blues and R&B - that music's in me, somehow."

Joining together with friends and fellow blues players Rick Mason, Jimmy Brown and Paul Tkac, Gillespie formed the Homewreckers in the mid-1980s. The band played the club circuit downtown throughout the rest of the decade into the 1990s.

During that time, a guitar rep named Mark Stein wandered into S.E. Davis Pawn Shop to market some of his wares to the owner. While talking about music, the owner mentioned to Stein that there was a great blues band named the Homewreckers playing down at the Whipping Post Saloon that night, and they needed a guitar player to sit in. Taking a chance, Stein went down and sat in with the band. The rest, as they say, is history.

"They told me to go back to school at first," laughed Stein, "but I knew once I got up there that I wanted to do that for the rest of my life. I had only played for myself at home before that, but after that I started really working."

Stein became a religious devotee of The Homewreckers and started his own band called The Steamrollers. Conflicts grew between Stein and the harp player in the band, however, and eventually The Homewreckers and The Steamrollers traded players, and Stein was a part of Gillespie's band.

After Stein joined The Homewreckers, the band went through some member changes - Byron Davies joined the band as bassist, and Andy Brown, vocalist with El Roostars became the drummer - and went through its final name change, to the 100-Proof Blues Band.

"We're proud of our Kentucky heritage, and our bourbon," said Gillespie, "and we wanted our name to reflect that. Plus, we're an honest blues band; authentic. We wanted our name to show that, as well."

Now comes the third and trickiest of all the music-legend omens: staying power. Together for more than 10 years, the 100-Proof Blues Band has opened and closed blues clubs in the area, seen the blues scene in Louisville ebb and flow, and still somehow they keep performing through it all. Day jobs have become necessary (Gillespie is a carpet layer with Attitude Carpet and Stein works at Dixie Music), but the blues remain the same, only deepening and gathering more flavor as the band moves into its second decade together.

"We see ourselves as warriors, out bringing the blues to the people," said Gillespie.

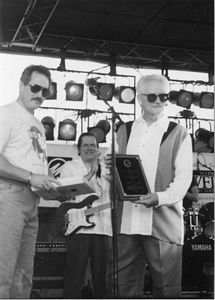

Now the band is settling into that state of grace where their status one of Louisville's legendary blues bands becomes increasingly apparent. Greg Martin, lead guitarist for the Kentucky Headhunters, said that seeing the band play for the first time years ago "lifted a veil" for him musically and set him on the path he is now. Blues critics speak in respectful tones about the band, and they are in the studio with Jeff Carpenter and Scott Mullins at Real to Reel, working on a CD they hope to release around Derby Day this year.

"Sam Myers, who's a great friend of mine, sat in with us when we played [WFPK's] Live Lunch recently," said Gillespie, referring to the well-known blues singer and harmonica player of Anson Funderburgh and the Rockets, "and then he came and sat in with us on a couple recording sessions, too, so he'll be on the album."

While talking with Gillespie and Stein, the stocking-capped bluesman from earlier in the evening put his beat-up guitar down and began dancing with the blonde-in-black to the rhythm of the blues tune pouring out of the coffeehouse speakers. Gillespie closed his eyes for a moment.

"Jimmy Reed," he said dreamily, and then smiled. "See? This music follows me everywhere." He leaned back in his chair. "There's something about the idea of living the blues," he mused. "Not that you have to live some hard life to sing it, but it helps to have been there and have that fire in your soul. This hasn't been an easy road I've chosen, but I would never choose any other."

Lamont Gillespie and the 100-Proof Blues Band can be heard on a regular basis at Churchill Blues Bar, where they are the house band for "the only bar on the South End still playing live music."