social bookmarking tools:

|

|

| Available RSS Feeds |

|---|

- Top Picks - Top Picks |

- Today's Music - Today's Music |

- Editor's Blog - Editor's Blog

|

- Articles - Articles

|

Add Louisville Music News' RSS Feed to Your Yahoo!

|

THE CHOICE IS CLEAR: VHS OR BETA

She couldn't have been much older than 21, the young woman standing behind the wait stand at Lucky Strike lanes: black flair slacks, black scoop-neck t-shirt with long sleeves, hair in a tight bun, a thin silver chain at the hollow of her neck. She looked confused, like a kid in grade school who had been asked to stand in front of the class and solve a story problem involving Fermat's Theorem and the Heisenberg Principle. About a minute before, I had told her I was waiting for four guys, a band that was supposed to meet me there.

Her eyes brightened. She was interested. "Who's the band?"

"VHS or Beta," I said.

The story-problem look flashed across her face for a few heartbeats. Then she blinked and laughed softly. "Oh, you mean that's the band's name."

It was a perfect non sequitur: she asked for a band's name, I gave her the two types of home video formats that were once available, a response that hasn't been given in its related context for nearly 15 years, one that is now just a footnote buried in the unwritten annals of cultural history, an answer to a trivia question.

I smiled at her and pointed to where my wife, Laura, and I had just finished dinner, at one of the sunken semicircular booths on the backside of the bowling lanes. I told here that was where we'd be waiting for them and walked back to the table. The bar across from where we sat spread nearly the entire width of the space the bowling lanes occupied at the Fourth Street Live entertainment complex in downtown Louisville. A wall of flatscreen televisions spanned the wall behind it: two large ones nearly the size of billboards checkerboarded by smaller ones. On the large ones was the ESPN pre-game show for the upcoming Cincinnati-DePaul contest. Behind us, the bump of a ball on wood, then the noisy clatter of pins sometimes followed by a shout of cheer. The place had been open since September. The smell of fresh shellac from the floors cut into the lingering odor of cigarette smoke and French fries.

My wife was there for pictures. I was there to get the story.

The screaming organ and Moog riffs in the Steve Miller Band's "Fly Like An Eagle" blasted from speakers in the ceiling. Behind us, the lanes were filling with bowlers and people who were just trying to look like they enjoyed hurtling a heavy plastic ball down slippery planks of wood. Laura leaned toward me. "Do you know what these guys look like?"

They would look tired, I thought: more than three straight months of nationwide touring since early October to support their fourth release Night on Fire and a couple of weeks off for the holidays, all before they were to play bus-and-van weekend trips in select cities for a month before heading off for showcase performances in England and Germany at the end of February.

Which raises a question: can you tell what band members look like by how they sound? Metal bands: long hair, shredded jeans, more tattoos than the crew aboard the U.S.S Nimitz. Alternative rockers: shorter hair, sallow faces, downcast eyes, more tattoos that the crew of both the Nimitz and the Abraham Lincoln.

A band whose sound is a throwback to that period when disco was waning and New Wave was subverting its place on the record charts, when studio sessions yielded either full and rich sounds with strings, synthesizer, heavy bass lines, and tight guitar riffs all wrapped around a simple, steady rhythm of high-hat, snare, and kick-drum (vanilla-white three-piece suits, black polyester tone-on-tone shirts, and matching Gucci loafers), or polished, snappy, cynical songs that reached back to the tunes heard all over the radio during the early years of the British Invasion (tight black rep suits, white shirts, and ties no wider than emery boards).

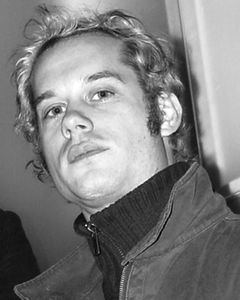

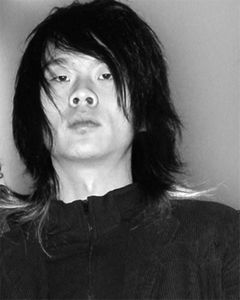

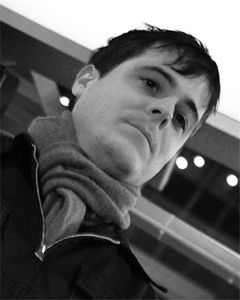

But the men of Louisville's VHS or Beta, drummer Mark Guidry, bassist Mark Palgy, and guitarists Craig Pfunder and Zeke Buck, arrived simply dressed for the weather: coats buttoned to their necks, shoulders hunched against the cold early January weather that had snapped back into the city after mild temperatures had melted away almost all of the snow that hit just before Christmas.

Now less than halfway through the worldwide tour for their Astralwerks release Night on Fire (their first major-label recording and the fourth one they have made as a band), VHS or Beta is at one of the milestones in a band's career very few can actually make, the one where their musical identity is either entombed or left free to grow.

"A lot of people have asked us about our last record and this record," bassist Palgy said, "and that's kind of only tuning into half of what we are. We've been around for eight years. So if you could ever hear where we came from to where we are now, it would answer more questions."

Their first recording was self-titled and, as the band described, full of noise (but, in a clever twist of marketing, a limited edition of it was produced on VHS video cassettes). The second, On and On, showed some maturity to where, guitarist Buck said, one critic called it "Gang of Four meets Kraftwerk" (think slamdance punk meets bleached, rigid electronica). But the record Palgy mentioned, the one before Night on Fire, was Le Funk, self-produced and released on the band's own label, On! Records. Six tracks, two recorded live at Louisville's Headliners Music Hall, of pure bootyshaking disco, with all the elements: synthed-up vocals, rhythm driven with high-hat and snare drum, handclaps, titles such as "Heaven," "Solid Gold," "Disco Paradise." When you hear it, you can't wait to dress up in polyester, spend hours styling your hair, and slathering your lips with strawberry-flavored gloss. Women might feel the same way.

The band nudged their sound into slightly into a different course with Night on Fire. The dance-yer-ass-off hooks are still there. The edges just aren't as soft. And this one has vocals from Zeke Buck, whose belty singing style has reviewers comparing him to 1980s New Romantics like Robert Smith of The Cure or Martin Fry of ABC.

"I don't think we'd be getting so many `80s references," Pfunder said, "if it weren't for people referencing certain things like vocals. People tend to listen to vocals first in music, then they go ahead and put whatever definition they find for that, so they're gonna lump us into this little category or this one."

"We try to think," Palgy said, "we have a sound [that's] not all of our own. But despite whatever genre people like to hook us on, definitely we all grew up in the `80s, but we have a lot of other influences as well."

Yet the band's choice of music style in which to play has sometimes led to a few challenges.

"I feel this band's had identity problems," Pfunder said. "We've had trouble fitting in somewhere. We were always doing something we really enjoyed doing. We're just this weird dance band playing music. Who're we going to open for? Why is that gonna make sense? It was always like a feeling of dislocation at certain times from the music scene. And then dance music started happening with a rock crowd. We finally started to feel somewhat relevant to times. In that sense, it's kind of like the second age of VHS or Beta. We don't feel so dislocated from things."

If this is the second age for VHS or Beta, the first age must have started when the band formed eight years ago. Pfunder, Buck, and Palgy had played in different bands, together or with others, and the three had conducted lots of jam sessions together. They then took the inevitable next step of actually making some music. One problem: they couldn't find a regular drummer.

"It seemed to be like a plague as far as VHS or Beta was concerned," Palgy said. "We went through a bunch of different drummers."

"It's a Louisville plague," Guidry added.

Palgy continued. "So we got to the point where we tried to find someone who'd been in bands before, someone who's reliable and solid and wants to do it. `Cause I think at that point, someone with heart and who wanted to play was more important that someone who'd been playing for millions of years."

One night their drummer didn't show up. The replacement? Palgy's roommate Mark Guidry.

"And the magic started," Pfunder said with a grin.

Still, why would four friends in their twenties, who had come together in the most common way that bands are formed, decide to risk dislocation and disenfranchisement and choose to play disco club tracks?

Zeke Buck made a small shrug when I asked that question. "It was our theme music while we were growing up," he said, "so it just kinda. . .came out.

"It's the music of our generation."

Comiskey Park, Chicago, July 12, 1979. WLUP-FM disc jockey Steve Dahl presents "Disco Demolition," where in between games of a double-header between the White Sox and the Detroit Tigers, Dahl promises to destroy the disco albums the spectators have brought to the game as admission (along with 98 cents). At Comiskey Park that night, bedsheet banners enscrawled with "Disco Sucks" and other choice phrases were held high and hung from the edges of the balcony. When Dahl walked out onto the field, the rabid passion of those in the stands was unleashed in a roar.

Truth to tell, disco had become tiresome and silly by 1979. Wayne Newton had put a thumpy beat and sweeping strings behind "Jingle Bells" to make "Jingle Hustle." There was a threat to extract Elvis Presley's vocals from some of his hit songs and lay them over new disco arrangements, which (depending on your belief about his demise) either caused him to turn over in his grave or start filling out job applications at more Burger Kings. It seemed that just about every musician who was on the charts in that decade had dipped their toes into the disco hot tub: Rod Stewart, the Grateful Dead, ELO, even Kiss. The urban grit of Saturday Night Fever was polished away and replaced with a silvery celebration nightclub life in Thank God It's Friday, then it mutated into something in skates and hot pants called Roller Boogie. "Disco Sucks" began gradually replacing "Love your nails, let's go share my personal space" as the mantra of the moment.

But now disco had reached critical mass. It was if Dahl and the fans had been armed with pitchforks and torches and had trapped the greasy polyester monster. Dahl had taken a pile of the collected records and detonated them along the third base line. After the last piece of charred vinyl fluttered to the ground, the fans drained from the stands and marched onto the field. In center field there was another pile of records. It was burning. The grass, designed to hold a maximum of 12 men at one time, was being tromped and scuffed by fans who had come to celebrate the symbolic destruction of the polyester monster, the music they loathed. The ones with DISCO SUCKS banners held them high.

When it ended, center field was scorched and the rest of the field was divoted, unplayable. The Sox had to forfeit the second game to the Tigers.

More than a quarter century after "Disco Demolition," Steve Dahl is still credited by some as having, in a stadium ritual of fire and smoke, single-handedly ended the disco era. Yet his contribution is disputable.

Maybe he's the guy who just forced the music back into the nightclub subculture from which it originally came.

And where it rested. Treated its own wounds. Waited.

Within that quarter century some of the children born during the shag-pile and avocado green decade fondly recalled that style of music, perhaps heard in their parents' cars or on an older sibling's Realistic stereo (with the wood grain finish and shiny, spring-button controls). Midway through the next decade the beat resurfaced in clubs, mostly in Europe, propagated by performers like Pet Shop Boys. Bryan Ferry continued to make his sultry dance hooks. A few years later hip-hop performers and club DJs begin sampling riffs from Rick James, Chic, and Taste of Honey. In nightclubs endless mix loops of that once-scorned music played for hours. Young people gyrated and slithered up against each other to it. The gray smoke that rose from the pile of burning vinyl 25 years ago was now cooler and brighter, generated by smoke machines cut through by colorful lasers and flowing around dancing youth. A young singer and producer named Jason Kay borrows a groove from Stevie Wonder and amps up the bass, calls his band Jamiroquai and sings of a virtual insanity. In Sweden, a band of five friends called The Cardigans make a few singles. One of them, "Lovefool," is snapped up by director Baz Lurmann and used as part of the soundtrack to William Shakespeare's Romeo + Juliet. Another, "Carnival," was heard in Austin Powers: International Man of Mystery. Both sounded as if they had time-warped from twenty years earlier to be spared the Wrath of Dahl.

Fortunately, though, bands like VHS and Beta and those mentioned above do not limit their musical range to the stuff they heard growing up. They're not part of the disco nostalgia machine, not touring with Thelma Houston, Evelyn "Champagne" King, or the Van McCoy Orchestra Reunion Revue. For one thing, the band's crowds are younger. For another, they have a manger who knows what the band is about and who got them a deal on a label that showcases music that crosses and blends genres, where hip-hop and techno is welcomed in the same house as singer-songwriter, New Age electronica, and pop.

In short, they're on a label that gets it.

Band manager Brian Long, of YesKnow Management in New York City, heard VHS or Beta in a show at the Knitting Factory, where they opened Radio 4, another act he manages. Long shopped around a copy of Le Funk, and found luck with the independent label he helped create: Astralwerks. It's the musical home for singer-songwriters Beth Orton and Badly Drawn Boy, the French pop electronica duo Air, mix-masters Fatboy Slim and The Chemical Brothers, Ben Watt (when he's not with his wife Tracy Thorn in Everything But the Girl), Radio 4, and the veterans of electronica: Germany's Kraftwerk.

"One of the weird things about us," Palgy said, "is that we're the first domestically signed acts for Astralwerks."

"Most of their acts are licensed," Buck said. "They bring the big acts from Europe here. We were the first band that they ever actually signed in their office. And they're pretty excited about the things that are happening."

But in a business where lots of naïve young musicians see the label deal the goal, there are some drawbacks. And, to be fair, some perks, too.

"There are a lot of misconceptions that the deal is going to save your life," Palgy said. "That you'll be happy, free, rich, whatever. It's a great thing, but it is a huge decision. Once you sign a deal you are bound to someone else who has a lot of say in how your music is made. It's a very, very touchy thing.

"Now it's not so much of a hassle," Pfunder said. "Calling manufacturers, getting invoices sent out."

"You can concentrate more on the music. But we do feel very thankful that we did find a great deal," Palgy said.

Part of the deal now involves their first music video, a straight-on performance piece shot by Waverly Films of New York, an extensive domestic and international tour schedule, Night on Fire now on the record charts in Germany, three different club remixes of the title track, and the licensing deals with Virgin Records in the United Kingdom and EMI in Japan and Australia.

"It's exciting to know that this record is getting such good feedback," Palgy said. "Things are still happening for this record. It's just starting to find its legs."

While coasting on Night on Fire (with the fifth album still "up here," Buck said, tapping his skull), the deal with Astralwerks, and a developing international interest in them, VHS or Beta remains a band that has found a niche for now, one that can easily become their springboard into new stuff. Like The Jam, the British band that hopscotched through post punk, new wave, and retro-soul, and from which its guitarist and lead vocalist Paul Weller formed the glistening pop of his next band, the Style Council, there is a vista of possibilities for them. They've gone from alt-rock noise to slick disco to dance-floor trance jams. All the while, they've maintained the one thing that all bands should have.

No, not a stable of women. Gratitude.

"I think a lot of bands put out their first record to a parade," said Pfunder. "They don't have to go through wondering why doesn't it seem to fit, or why don't people care about what they're doing. I think it's good for us to have gone through an uphill climb to where we've been. I figure you couldn't be talking to four guys that really appreciate anything that comes our way.

"We took the long road to get here. It's fun now."

Get a groove on: www.vhsorbeta.com