social bookmarking tools:

|

|

| Available RSS Feeds |

|---|

- Top Picks - Top Picks |

- Today's Music - Today's Music |

- Editor's Blog - Editor's Blog

|

- Articles - Articles

|

Add Louisville Music News' RSS Feed to Your Yahoo!

|

A Carpenter's Touch:

Jeff Carpenter and the Magic (and Reality) of Al Fresco Place Studios

I can't tell if it is the way the wood is bent on the wall or the pattern on the vinyl floor tile, but I have a slight dizziness as if I'm standing in a small room in a funhouse, the old kind that used to be at Fontaine Ferry park, permanent fixtures instead of the fold-out trailers that get parked in the midway at a fair, where you walk in and out in less than two minutes. I think that I'm going to turn and walk back and slam my face into a maze of mirrors and then wobble into a large rotating concrete barrel and hope not to slide down on my ass.

Instead, I shift my eyes to focus on the twin-paned window cut into the center of the bent wood wall, then down to the Roland electronic keyboard in front of it. The dizziness fades, but I still have to turn away so I don't spin around and collapse or lose my dinner all over the Roland. Hard to clean between the keys when that happens.

It is a partition, actually, made up of overlapping planks of bent wood planks about five inches wide and a quarter of an inch thick. I speak a few words. My voice is trapped in that one space and doesn't travel out into the rest of the room. It comes back into me in a rich timbre without the ring of room noise.

"I asked him if he needed to dampen the wood in order for it to bend like that," a man's voice says from somewhere off to my right. "He said he didn't think so and just went ahead and bent it."

The window at the back of the partition with the curved wooden wall looks across the floor and into the window of another room, where a slender man with a shock of spiky white and gray hair (with a few hints of remaining black) is seated in his wheelchair, his fingers flicking switches to turn off racks of audio equipment. The view into the other room is blocked by a dark gray rectangle. It's the back panel of a large computer monitor that is part of his latest equipment addition: the Radar 24, an all-digital audio recording system.

The components are simple: a monitor, a keyboard (more square than normal for a computer) and a dense black box. It is an example of what's called AM/FM technology in audio processing. AM is Absolute Machinery, the inputs, outputs, microphones, mixing boards, keyboards, even the cables that run from output to input. The box, though, that's FM technology, Freakin' Magic (only the rougher cousin to the word "freakin'" is used), where something marvelous happens to the stuff the AM technology brings in, then it is released back into the world as pure, clean audio.

The whole studio space itself has been altered since I had last been in it eight years ago for my story on Bryan Hurst and the Lolligaggers. They had recorded Waiting for Favors there, as had Heidi Howe with her debut Nature of My Wrongs (and would return later for A Real Piece of Work). Lexington's Crown Electric had commuted to the place several nights a week to record Rockabilly Opera. Tim Krekel had been there, with his Groovebillies, to record L&N and round out the sessions started at another studio for Underground. Serpent Wisdom was scheduled to come in for what would become Fat Lotta Good. Back then the floor was empty. At one side of the room, a corner had been walled off to form a vocal booth.

It now looked. . .well, like someplace you'd find on Demonbreun Street in Nashville or Hollywood Boulevard in Los Angeles. Not something you'd find in the renovated basement of a home in Louisville's Belknap neighborhood.

But what Jeff Carpenter's AlFresco Place Studio lacks in sleek urbanity, it makes up for in warmth, as welcoming as a church.

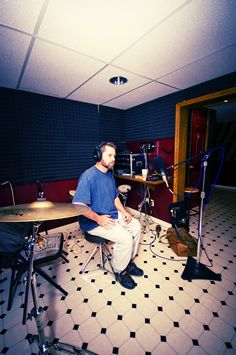

The curved-plank wall was the idea of his new associate, Louisville session drummer John Hayes, who had contributed the bulk of the ideas for renovating the studio.

"He said 'I wanna build this and I wanna build that', Carpenter reported. "He put his ideas and craft into it. One thing led to another and we started working together. He's been helping me with recordings and stuff. I think we'd call him an asset. It's worked out well. I think some of the changes he's helped me make have brought the studio along to where we were hoping to get it to be."

Formerly known as Reel to Real Studios, its official name when Carpenter and his partner Mick Puckett opened it more than three decades ago in its original location on Taylorsville Road, the facility gradually took on the name Alfresco Place, not only because that is the name of the street where Carpenter moved it, but mostly because anyone who recorded there fondly referred to it as "Al Fresco's Place," as if it were a comfortable neighborhood pub and Carpenter served the drinks and dispensed advice wiser than any narcissistic New Age guru can casually toss out at a $500 seminar. And he doesn't have pricey videos and books for sale in the lobby.

"You'll find out in the music business that nobody cares about your band," Carpenter said. "What they care about is trying to move units and sell product. If they think you've got something, they'll talk with you and see where they can tape it."

"They won't pull punches with you," John Hayes added.

"They'll sit you down as say, 'We like this, but we don't like this.' And a lot of times, even if somebody gets somewhere and gets signed, they'll find themselves playing with a lot of different people than when they started out."

Normally, this kind of knowledge comes from someone who works in front of the board, a manager or a tour-weary musician or a producer. But you can't be in an industry for most of your life and not absorb its gravel-harsh realities. Even if it is an industry you never planned to get into at the beginning.

"I actually started out in radio and took a left turn somewhere," Carpenter said. "I struggled with the idea of being a DJ. At one point I didn't know if I liked doing it. I got more interested in the technical side of stuff. All my buddies were into music, so it was kind of a natural transition."

After learning his behind-the-board skills at the WHAS radio school and getting his FCC license through a school operated by WINN country radio (their studios were in the building at Third and Broadway, the station's call letters hanging perpendicular from the corner of the building in four large cubes that slowly rotated), Carpenter worked briefly at WKLO, one of the Top 40 young audience stations in the city. He left the world of 24-hour DJ glamour to take a position recording and mastering acetates of book recordings at the American Printing House for the Blind. There he met Mick Puckett, who would later become his partner in setting up Reel to Real. That came after engineering jobs in two other studios.

"I had bounced back and forth, doing a stint at Allen-Martin when Bobby Ernspiker was out there, for not quite a year. From there I worked with Tommy Cogsdon when he had his studio above Mom's [Musicians General Store, the old location on Frankfort Avenue]. He called it the Crescent. From there I moved into the place on Taylorsville Road and was there for 14 years. We've been here for 10. It's amazing how fast it's gone."

The welcoming atmosphere of the latest iteration of Alfresco place, in the basement of the home where Carpenter lives with his wife Mary Kennedy and their son Declan, fits the honest, forthright attitude of its proprietor when he's approached by musicians needing a place to record and develop their material. He asks a set of questions of anyone who wants to book time at Alfresco Place, no matter if they're a group of teenagers who want to move from a parent's garage into a professional recording environment, or a band of professionals shopping around for a place to record their latest works.

So imagine a conversation between Carpenter and a musician with a burning desire to finally get his or her songs, which he or she thinks rival anything from the pen and guitar of John Denver or Ani DiFranco. The young musician calls. . .

Hi, I'm looking for a place to record some songs and make my first CD. What's the process?

"I generally ask do you have your own band," Carpenter said.

Well, no, it's just me, but I was trying to get some guys together.

"My next line is going to be that I've got a lot of great guys that I work with all the time that play in the studio for me. I can get you drummers, bass players, guitar players, whatever you need."

I don't have a lot of money. How much does something like this cost?

"That's when the phone goes dead," Carpenter's wife Mary said.

"More often than not, that's the case," Carpenter said (the caller not having a lot of money to spend on a production, that is, not the phone going dead). "I'll ask people what kind of budget do they have. What are you looking to do? How many songs? How much production do you want? Do you want to make it sound like a basic three-piece band or four-piece band? Do you want just do it acoustically? Are you going to shop it as a demo to pitch the songs, or are you looking to put it our yourself as a CD?

"More often than not, somebody wants to put out a CD. Generally, we kind of hone it down to what they can afford and put in some sort of package together."

Do you handle all musicians and projects this way? I've got my own band and I don't want to use any other musicians and we've got some guys from Sony and Universal coming to see one of our shows. When can we come in?

"I can work you in over the next three days. How about we do something pretty much live in the studio? If these guys are coming in to check you out, they're probably wanting to hear you more stripped down than sitting in here doing a lot of production. So let's put the rhythm tracks down, track some throwaway vocals, then you can come back in and do the real vocals, punch in some solos, fills, whatever needs to be added. We'll capture your band more as is as opposed to shifting into a lot of production."

Fortunately, Carpenter has had many pleased clients who have entrusted him with making them sound good. Rarely, though, will he have someone who isn't pleased.

"Every once in awhile there's the person who's gonna go, 'That can't be us. What'd you do?' I even had a band once, a long time ago when I first started out, come to me. They heard it back and they were so embarrassed and apologized to me. They paid me, plus a little something extra and said, 'We just can't do this.'"

"I would say one of the things where Jeff does a really nice job," Mary Kennedy said, "is encouraging people to get really good musicians to play on a recording, especially if they're going to put a CD out."

"It's hard to tell somebody that, though," Hayes added. "'Cause really, it's about the vibe."

"At one point," Carpenter said, "you size up things for yourself. Are you in this for the fun of it and enjoying making your music? Or are you wanting to get to the next level. If you're gonna shoot for doing this for a living or you want to get a record contract, or even if you just want to pitch your songs, then we're gonna have to raise the bar a little bit. And you'll have to consider if your playing is up to snuff. Maybe what you really want to do is see if you can't pitch a song. In order to put it in the best light, maybe you ought to have somebody else play on it. If that's where you're going."

For novice and professional musicians, Carpenter's process and the questions he asks before he takes on a project get them to think a great deal before the first note is recorded. It helps form a plan, a spec, if you will, so that neither side will waste time or money by just merely recording stuff from the first day in the studio with no direction (home or otherwise). It forces both parties to focus on a result. And even then, it is only a first step. If the musicians are wanting to make a CD, there's more to deal with.

"The biggest thing I think is funny," Carpenter said, "is the issue of actually doing the CD. This band may have only been playing around for a month or six months. Even if they have some sort of track record, it's still a lot of work to sell that CD. That's when the real work starts. And I think people, most of the time, get disillusioned. They did all this work, they put it in the stores. It's a limited vehicle to work with."

Sometimes the projects he's worked on have gotten to that next level: a band gets a record deal, the brass ring of anyone who has dared to think him or herself as a musician.

Sometimes, all his work is undone after that happens.

"What's happened in the past with people I'd worked with," Carpenter said, "who have gotten somewhere, the label's going to bring in a producer, they're going to go to a place they want to work with and they're going to re-do everything. You try to shoot is as close to all those marks as you can. Of course, you're not always gonna hit a bull's-eye with it, but I think you have to size up when somebody comes to you where they're coming from as ask if they're doing it for their own enjoyment or if they want to get out there and sell CDs."

With so many musicians passing through Alfresco Place, do any of them stand out as being difficult? Have there been any challenging projects?

"I really don't feel like anybody's been terribly difficult at all," Carpenter reports, "or a huge challenge. I think the challenge is in between, when you've got the Stella Vees [a blues band], who want to sound like the old blues records, who want to darken down the sound. You think backwards. To go from that and have guitar-based, screaming heavy metal like Rifle, where the bass player wants his cabinet double-miked, who wants the bass sitting in your lap. We're switching gears really quick and we've just come off this folk album where we're capturing the delicacy of a hammer dulcimer. So I think that's the challenge. To make the switch."

While technology has altered the process of making a recording, so that anyone with a computer, microphone and a small mixing board can record, mix and even master their own work, to actually make the effort to go into a studio and cut some tracks may seem archaic, almost quaint. Very 20th century.

Still, there's one benefit to cutting a recording in a studio: oversight. Another set of ears (and eyes) to check playback, offer suggestions and solutions, to help plan a recording and determine what exactly the musicians are wanting so that the sessions will go in a direction that will make everyone happy and feel as if money and time is being well-spent.

Jeff Carpenter's Alfresco Place has provided that oversight for a number of projects for Louisville musicians, in a space that's comfortable and works for all types of music.

"People just like it here," Hayes said. "It feels good. Jeff's one of the few people in the music business who will tell you like it is. He's fair and honest with you. You just don't get that in this business. It's usually what can I do for you here, instead of how can I get you."