social bookmarking tools:

|

|

| Available RSS Feeds |

|---|

- Top Picks - Top Picks |

- Today's Music - Today's Music |

- Editor's Blog - Editor's Blog

|

- Articles - Articles

|

Add Louisville Music News' RSS Feed to Your Yahoo!

|

Let me tell you about ...

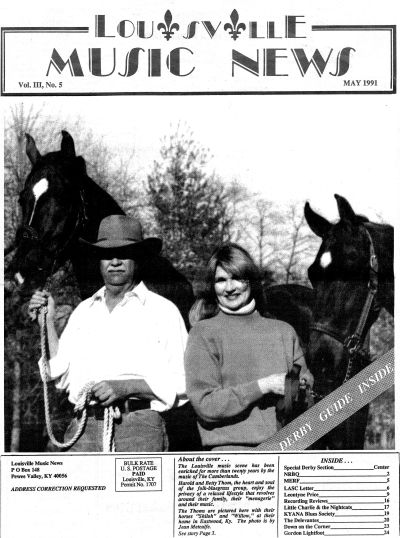

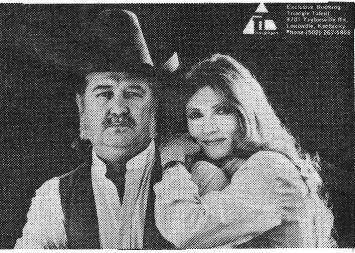

Harold and Betty Thom

Heart and Soul of "The Cumberlands"

By Jean Metcalfe

Harold and Betty Thom, the heart and soul of the excellent and enduring folk-blugrass group The Cumberlands, hail from Shreveport, La. They met at Byrd High School, where both played trumpet in the school band. At age 14, Betty was too young to date, but by the time she was 16 she and Harold were "dating seriously."

"So we've been together ever since. And we've just practically grown up together almost," Betty said.

Instead of going away to college and studying ballet with the late Martha Graham as she had originally planned, Betty decided to stay in Shreveport and attend college with Harold. She majored in art and minored in music, continuing with all the things that she loved, including ballet.

"You had to do this (go to college) in the South when I grew up," Betty said, "before James Dean came along and changed everybody's mind, and everybody got wild and wore black jackets."

"I played music and was into ballet and art and horses and anything with four legs and a tail," Betty laughed.

"But it was taking a back seat to Harold because I loved him so much. And you know how it is when you're young and in love."

Harold, who has "always loved to perform," would entertain at all the school functions. When he was 14, "The Louisiana Hayride" was in full swing, and many "blossoming superstars" were on the show. The list includes Bill and Charlie Monroe, Johnnie & Jack & theee Tennessee Mountain Boys (with Kitty Wells playing upright bass), Lefty Frizzell, Carl Smith and Hank Williams Sr. ("the biggest star to come out of the 'Hayride,' except for Elvis," Harold said.).

Radio station KWKH was the home of "The Louisiana Hayride," and Hank Sr. had a live radio show on the 50,000-watt clear channel station in the morning. That was in about 1947-48, and young Harold would stop in to catch the show before going to school. "It was just him and his D-78 Martin (guitar) and a steel guitar player," Harold said.

"One morning I went in the studio after he finished and he sorta took pity on a 14-year-old and taught me my first chords on guitar. So that's really where I got extremely interested in learning to play and sing," Harold said.

One of the staff announcers at KWKH was Jim Reeves, who was deejay for a late-night show called "Red River Roundup," which came on after "The Louisiana Hayride."

"One night he, for a lark, just did a song live on the show with the house band backing him up, and someone from RCA Records was there and heard him and liked his voice and signed him, and that's how Jim Reeves got started," Harold said.

When Harold was 16, he had his own band, The Red River Playboys, a straight-out, but selective, country music" group, and he had a thirty-minute radio show five mornings a week on a local radio station.

Harold worked in radio in various capacities while in college, and in January of 1954, after attending a television production school, he went to work for the new television station in Shreveport, KSLA-TV, Channel 12, as their first camera man. Two and a half years later, having worked his way into the position of director at KSLA, Harold moved to Lake Charles, La., where he was operations manager of a small UHF television station. After eight months he moved to Alexandria, La., where he was a producer-director at KALB-TV, Channel 5. The year was 1956, the same year that Betty and Tom were married.

Betty transferred from Centenary College in Shreveport to Louisiana College in Alexandria.

"I was pregnant and in college, and we were very busy," Betty related, laughing at the recollection.

Harold's association with KALB-TV lasted for ten and a half years. His marriage to Betty lasts to this day.

Harold was directing a live weekly country music show on KALB, and one night one of the show's guests played a five-string banjo.

"I called Betty and told her to watch the show that night 'cause the guy was really good," he said.

"And I had never heard a five-string banjo player," Betty laughed, adding that she just couldn't believe what she was seeing. She "just loved it instantly," she said, adding that she had had that same reaction to the Dillards.

Harold invited "the guy" _ Jim Smoak _ "out to the house to have some hamburgers and pickand sing. I dragged my guitar out of the closet ... and we (Smoak and both of the Thoms) started playing on weekends and around the house just for fun."

Smoak had previously been in the music business to a greater extent, but had "hung up his banjo" and moved to Louisiana where he was working as a professional photographer when the Thoms met him.

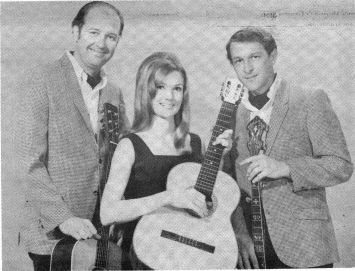

The new trio's first paying job was a performance for a Kiwanis Club meeting, Harold recalled, "And I think we made $75."

"That was during the days of Peter, Paul and Mary," Betty interjected, and so we were the PPM of Alexandria, La."

They had to come up with a name in a hurry because they were playing that evening. "And so we thought, 'folk music.' 'Cumberlands.' 'It sounds good,'" Betty explained.

Harold said they were doing a lot of Appalachian folk songs such as "Darling Corey" and "Cumberland Gap" and they thought that "The Cumberlands" fit their image; the majority of the music they were playing was from that area.

Soon they were playing at the local Ramada Inn on Friday and Saturday nights, and it wasn't long before they began to fill the room, so they added Wednesday and Thursday nights to their schedule. They played at the Ramada for about three years.

"And we just sorta clicked in Alexandria, and we were 'top drawer,' if you can call it that, in that little town," Harold said.

Smoak's prior contacts in the music business served the Cumberlands well. He had appeared on the Grand Ole Opry with Bill Monroe (and was on the road for two years with the legendary "father of bluegrass"), Hylo Brown and others. He was part of the band that subbed for Flatt & Scruggs when they couldn't fill engagements due to "The Beverly Hillbillies" commitments. (Flatt & Scruggs had a hit with "The Ballad of Jed Clampett," the theme song for the popular television show.)

Harold asserted that at one time there were only two "really good commercial banjo players in Nashville and they were Earl Scruggs and Jim Smoak."

The Cumberlands did a guest shot on the Grand Ole Opry, got an encore that "really turned us on," and were invited back for a second appearance.

They got a record deal with Dot Records and recorded their first national release single in Nashville. There would be other albums and other singles, on such labels as Chart Records and Starday-King.

At about that time all the coffee houses began to spring up, Harold said, and "it was a wonderful, wonderful time to be playing, because you met so many great people."

The Cumberlands played The French Quarter in New Orleans for about a year in the Bayou Room, which had folk music, and in hotels and free-standing clubs all over the country.

Folk music was becoming very popular, and groups such as the Kingston Trio, Peter, Paul and Mary, the Limelighters and others, were appearing on television shows such as the Ed Sullivan show, the Bell Telephone Hour, and an ABC show called "Hootenany," which used three or four different folk groups every week, Harold said.

"And so the whole thing just exploded and everybody was folk music crazy, and we just happened to be right there in the midst of it.

With two young daughters in school, the Thoms looked for a way to stay in Alexandria and play music. They leased a night club called "The Red Horse Inn" which seated about 75 people, playing there for three years. On the occasions when they did go out of town (to record in Nashville, for instance) they would hire performers to fill in for them at their night club. One such performer was the banjo player for the Glaser Brothers Band. His name was John Hartford.

Hartford played solo at the Red Horse Inn for two weeks, doing only songs that he had written, including "The Washing Machine Song" and "Gentle On My Mind." According to the Thoms, Hartford "went over passably."

Hartford gave Harold an autographed 45 record of "Gentle On My Mind" and asked him to put it on the juke box. He told them that there was a fellow who had just recorded "Gentle On My Mind." The fellow's name, he said, was Glen Campbell.

"They tell me it's gonna be a hit," Harold quoted Hartford.

"I hope to the devil it is for you," Harold told him.

About two months later the song came out and went to number one. Hartford went on to be a part of Campbell's television show, which was a summer replacement for the Smothers Brothers' program.

Betty spoke of how when Hartford first played their club the audience had accepted his original songs only politely at best. After the success of "Gentle On My Mind," Hartford made a return appearance and packed the club. After that they couldn't afford to bring him back.

"John went from $400 a week as a single to $5,000 a week on the CBS Glen Campbell show just to stand up in the audience every week and kick the show off with 'Gentle On My Mind' and then a couple of bits inside the show," Harold said.

Byron Berline who was stationed with the Army at Ft. Polk, La., about 45 miles away, came into the Thoms' club one evening, his fiddle in tow. They were aware of him, Harold said, because of the album Pickin' and Fiddlin' that Berline had done with the Dillards, which they really liked.

"He said, 'I'm goin' crazy over here at Ft. Polk with nothing to do ... I'm just looking for someplace to play.' And I said, 'Well, you have found it.' So every weekend for the next yearByron was a part of the Cumberlands. So he was, in effect, our first fiddle player. And we're still good friends ... and every time he comes to town ... we always get together."

Harold mentioned that Berline had gone on to play fiddle on "Honky Tonk Women" for the Rolling Stones and had been on the road with Emmylou Harris and had played on all her albums. He also played with the Flying Burrito Brothers and later formed "a really great acoustic trio, Berline, Hickman and Crary," Harold said.

Harold also said that Dan Crary was from Louisville, and had been a member of Bluegrass Alliance before moving to the West Coast. The Bluegrass Alliance at one time counted among its members Sam Bush and Ebo Walker, who left to become members of the group New Grass Revival. The talk continued to include New Grass member John Cowan, who was once married to Jonell Mosser, who went to school with the Thoms' daughter .... . And so it goes.

The Thoms said that although they went to see Mosser when she appeared in Louisville recently at Aor Devils Inn, they don't go out and stay late like they did when they were younger.

"We used to get up at noon and go to bed about 6:00 in the morning. Now we get up at about 6:00 in the morning and get in bed about 11:30," the Thoms laughed.

And although they still do gigs, Betty said, "We don't play six nights a week or five nights a week like we used to. We look back and say, 'How did we do that?'"

"Well, I'll tell you," Harold said, "We had American Saddle Bred show horses, we had two daughters in school, we had dogs and cats ("We had a menagerie," Betty interjected with a hearty laugh) and when we would go on the road I would get permission from our daughters' principal and teachers that they would get their homework a month in advance and we would leave and go to the Gulf Coast, to Florida, to Charleston, S.C., to Savannah, Ga., and ... they would do their homework in the hotel room. When we got back they handed it in and they made straight A's."

They couldn't always take the children along, but in the summertime travel with the children wasn't quite as difficult.

Harold reminisced about the days they played the rodeo circuit as the back-up band for such stars as Dale Robertson, "Little Joe" and "Ben Cartwright" (Lorne Greene and Michael Landon).

"At the intermission ... in a coliseum of 12,000 ... at the intermission the announcer would say, 'And now, ladies and gentlemen, the star of the NBC television series "Bonanza," Little Joe Cartwright.' And Jim (Smoak) and I would play the theme from "Bonanza" on the banjo and the guitar." (Harold is breaking up at the recollection and Betty is laughing gleefully. Harold imitates with his voice the "Bonanza" theme.)

"And he'd come roaring out of the chute on this horse, and he'd run out to the middle of the arena, fall off the horse, and get up and draw both of his guns and shoot a bunch of blanks, and then get up on the stage. And by this time we had run out and got on the stage behind him and he would sing maybe one of two songs, then he'd get on the horse and ride around and shake all the kids' hands and then ride off. And that was his show."

"And got paid a nice paycheck," I suggested.

"Ohhh ...... $25,000 a night."

They said that Dale Robertson did much the same thing, but that he was an experienced horseman, had a nice singing voice, and that his favorite song was "Ol' Blue."

A visit by entertainer Molly Bee to the Thoms' club in Alexandria led to the Cumberlands touring with her, playing county fairs, concerts, and other venues in such places as Los Angeles, Stockton, and Lake Tahoe. It was while playing in Lake Tahoe that they met Bobby Goldsboro, Roy Clark, and Roger Miller, who were playing in Reno at the time. The guys would come to Tahoe and sit in with Molly Bee and the Cumberlands.

"So for about three or four weeks we were backing up Roy Clark, Roger Miller, Bobby Goldsboro and Molly Bee," Harold chuckled.

Roy Clark was just beginning to really get into playing the banjo, Harold said, recalling that Clark and Jim Smoak would sit around and pick banjo together.

Of Roger Miller, Betty said, "People in Nashville didn't understand him. He was on another wave length. When he used to come in to our shows he didn't wait until the show was over. He used to just walk out in the middle of our show. ... When Roger felt like it he just walked out on stage."

Harold picked up the story, describing how, in the middle of a Molly Bee ballad, Miller would come up behind her onstage, and begin to cut up, without her knowing what was happening _ at least for a while _ until the audience's laughter provided the clue.

"It would turn into an hour and a half of ad libbing, and singing and playing. It was really interesting," Harold said.

The rock group Moby Grape, was playing in Tahoe while they were there.

"They were in love with bluegrass," Harold said.

"They couldn't believe the banjo player. They were really interested in it," Betty added.

Molly Bee threw a big party when the gig was over, Harold said, and invited Moby Grape. They told Smoak to be sure to bring his banjo. He did. And Harold brought his guitar.

Harold related, "They were totally engrossed in the fact that you could get that much music out of a banjo with three fingers playing the melody and the accompanying notes. ("And nothing plugged in," Betty laughed.) So they were enthralled with Jim's banjo picking."

During the last six months that the Thoms had the Red Horse Inn, they were booked, in June of 1969, for two weeks at the Colonial Inn Motel in Jeffersonville, Ind. (It was a folk room at the time, Harold said, where the Kingston Trio and other big names in folk music had played.)

Betty had always loved American saddle horses, so the Thoms crossed the Ohio River to look for Rock Creek Riding Club. They got lost en route, but they found and fell in love with Louisville. They could see the potential for playing their music here, they said, as there was at the time only one group playing similar music. That group was the Bluegrass Alliance, and they were appearing at Louisville's Red Dog Saloon on Washington Street.

The Thoms and Smoak went one evening to see the Alliance play. The members of the group were Lonnie Pierce, Dan Crary, Buddy Spurlock and Ebo Walker.

"They were a really good, tight band," Harold said.

The Cumberlands introduced themselves to the Alliance at the end of the set, and the Alliance invited them to play a guest set, which they did.

"It was one of those nights ... and it (the guest set) went over like gangbusters," Harold said.

The club's owner-manager asked the Cumberlands if they would play at his place when the end of the Bluegrass Alliance's long run there was over. It would be at the end of the following week, he said, although he hadn't yet told the Alliance. On that basis, Harold said, he agreed to take the job. It was not their intention, he added, to take someone else's job. They hadn't gone to the club looking for work.

"We have felt guilty, I think, ever since," Betty said, "because we felt like somehow we made them think, possibly, that they were let go because the manager heard us and wanted us to come in and take their place." She expressed concern that the Alliance might possibly have misunderstood how things really happened.

"I don't think Lonnie Pierce ever forgave us," she laughed nervously.

"In fact we invited them over to our house shortly after that whole thing went down, Harold said, "and Dan Crary was coming in my front door, and it was in the wintertime (Crary was wearing a heavy outer shirt) and I said, 'Here, let me take your shirt,' and he says, 'Well, I think you've already done that.'"

Both Harold and Betty laughed at the recollection, but there was a hint of lingering concern.

After deciding to stay on in Louisville, Harold called Gene Snyder, owner of the Joni booking agency, and he signed the Cumberlands. Six months later, in 1969, the Thoms moved into a rented house in Louisville.

Following a subsequent appearance at the Red Dog Saloon, they returned to Louisiana to play at the Red Horse Inn on New Year's Eve. Then it was back to their new Kentucky home.

They played at Arnie's Pizza King in Lafayette, Ind. (a "wonderful place to play") several times a year for twelve years. Many well-known groups have played at Arnie's, Harold said, including John Hartford, the Hager twins, Red, White and Bluegrass, and others. Besides Lafayette, they also played dates in Bloomington and Columbus, Ind.

While playing at the Red Dog Saloon, the owner of the Pine Room on River Road hired them at twice their salary.

"The Red Dog Saloon and the Pine Room was where we, I think, converted most of our fans in Louisville," Harold said. Later, when Eddie Donaldson bought the Red Dog Saloon, he also booked them into another club he owned, the 118 West Washington.

The Pine Room sorta became their home base, Harold said.

"It was really a nice place," Betty said, "and we met a lot of people there that we still love today. Everybody went there ... good food, good music. It was a Louisville landmark."

We spoke about the fact that it had since burned down, and Betty said, "People went out there to get the bricks."

They did private parties and conventions on weekends and "word got around Louisville that we were a decent, good group," which led to other gigs. One such was at former Louisville lawyer Scott Hamilton's Ramada Inn, where they were booked on a regular basis at double their then-current pay. On weekends they would move to the Ramada's 500-to-600-seat convention center because of the large crowds they were attracting.

"And every Friday and Saturday it was jam packed," Harold said. They played there for two years.

Meanwhile, free to take other gigs, the Cumberlands accepted an invitation to play with the Kingston Trio in Reno, Nev. They not only opened for the famous folk group, but would come back onstage to be part of the Trio's act as well.

During their three-week engagement at the Sparks Nugget Hotel, they met many entertainers, including Red Skelton.

Said Harold, "We'd come back here and play for a month, go out on the road and play for two weeks, come back and play for a month or two, go out on the road ...."

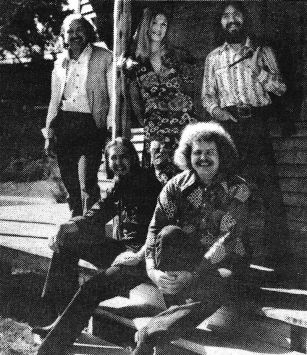

In 1970 the Cumberlands added bass player Charlie Faught to the trio of Harold and Betty Thom and Jim Smoak. That foursome made up the Cumberlands that played the Pine Room.

While they were playing the Ramada Inn, they hired their first drummer, Don Szymansky, and the Cumberlands became a five-piece group.

In 1973 Jim Smoak left and they hired Dave Cosson to play banjo. When Szymansky left they replaced him with Bill Lewis, who Harold said is now a session drummer on the West Coast, playing for such performers as Maria Muldaur.

Next they hired a pedal steel palyer, Tom Britt, who is now Jonell Mosser's band leader. Britt also played lead guitar. When he left, they took on Dave Seebolt, who played bass with the Cumberlands for about two and a half years. When he departed, they hired a succession of bass players.

A total of 34 musicians have played with the Cumberlands over the years, including Jeff Gurnsey (now with Steve Wariner), Ronnie Parton, and, for about four months, Steve Ferguson.

We spoke of how incredibly talented Ferguson is. The Thoms said that they have been following his career, and are hopeful that his new album project will be very successful.

The talk turned to the use of drugs by musicians in the Sixties and Seventies. Betty said, "We were sorta in the peace and love movement thing, but we never participated in the bad parts. We had children. I revered my family too much to do those things. I would not hurt my family for anything. We were surrounded by it. It was the thing to do. No one realized what a devastating effect it would have on the body."

"There were .so many good things about the Sixties ... peace and love and harmony ... good food ... health food. That's where I got into the health food. I am probably the only half-preppie, half-hippie," Betty laughed.

They talked about how the pendulum is slowly swinging back to acoustic music, and we mentioned Hall & Oates, Paul McCartney and the Dillards.

"What else can you do after you've done everything electronically that you can possibly do?," Betty asked.

"We have gone through some times, in my opinion, that we have just heard some godawful music," Harold said.

Have the Cumberlands stayed acoustic?, I asked, momentarily forgetting earlier parts of our conversation that had provided the answer.

"No," Harold patiently replied, "we use amplifiers and we use an electric bass, we use drums and we use a P.A. system, of course, but we've never been a fuzz-tone country-rock or rock 'n' band. We try to fix our sound where everything is pleasing so that it sounds like you're listening to a record, which, of course, is the ideal music-mix situation.

Harold Thom has produced eight albums, and he told me that they try to get their sound the same for every gig. He usually runs the sound from onstage because he has found very few people who can mix acoustic music well.

Harold named some of the groups they like to listen to: Poco, Burrito Brothers, The Band ("wonderful group"), NRBQ, Bonnie Raitt, Don Henley, the Byrds, Dylan ("in his early period, and some of his rock stuff") and Eric Clapton.

"But we've never been just a wide-open, screamin' rock 'n' roll band. What we have done, and I think successfully, is we have married bluegrass, folk and country music into a cohesive type sound, which is exactly what you find the Desert Rose Band doing today ... one of the best bands that's come along in years."

We spoke of the talent of Desert Rose's Herb Pedersen and the fact that he used to play with the Dillards, and that local musician Steve Cooley now plays with the Dillards, and that they were in town last month to appear on a Louisville Home Performances show. Harold then reminded me that Cooley plays with the Cumberlands these days, as one of three banjo players they use. When Dave Cosson can't play, then either Steve Cooley or Jim Smoak plays banjo for them. (And it's musical chairs time again.)

Depending on the event, the Cumberlands can play as a trio or as a group of up to six or seven performers. Trent Shaftner, who is married to the Thoms' youngest daughter Mary, is currently the bass player for the group. Shaftner once played with the Ides of March, a rock group, and for two years with The Kentucky HeadHunters, "before they became the HeadHunters, when they were still just a bar band in Bowling Green," Harold said. (More musical chairs.)

Shaftner is a part-time musician, selling bulldozers for a living.

The Thoms' oldest daughter is Elizabeth Tyler, whose husband is also in the heavy equipment business. Both daughters live in the Louisville area, and each has a son. Corey, 3, belongs to the Tylers, and Trey, who is 2, is the Shaftners' son.

Harold and Betty Thom live in Eastwood, Ky., in a comfortable southern plantation-style home, a nod to their Louisiana origins. The atmosphere is one of relaxed enjoyment. Enjoyment of their privacy, their children, and their "menagerie," one member of which is a dachshund named "Shady Grove." "Shady Grove III," to be exact. Two others Thom canines have had the name.

All of their animals are named for songs, Betty explained. Harold's horse is "Shiloh," named for the first song he ever recorded, "The Drummer Boy of Shiloh." Betty calls her horse "Willow," from the song "Wind in the Willow." (Hmmm ... "Corey" ... "Trey" ... hmmm.)

Our conversation turned once again to days gone by. We spoke of Ken Pyle and Sheila Joyce, owners of the Rudyard Kipling Restaurant, who used to own a place called the Storefront Congregation.

"We used that as sort of home base. It must've been about '70 or '71," Harold recalled, mentioning that it was when they were also playing the Red Dog Saloon and the Pine Room.

"She (Sheila) used to make some of the best Irish stew I ever put in my mouth. I used to look forward to going down there and playing. And we used to do a jam session on Sunday afternoon and I would wait and eat my supper when I got there ... Sheila's Irish stew.

Harold mentioned some of the illustrious musicians who had played there. There was Ralph Stanley, Sam Bush and Bluegrass Alliance, to name but a few.

"Louisville has been real wonderful to us," Harold told me. "It sorta took us under its wing and we have done extremely well here.

"However, the music scene began to change drastically in about ... the early- to mid-Eighties. So many clubs began to do away with the listening type of room and began to go to either all rock 'n' roll or all 'everything goes.' You've got live bands ... pool tables ... electronic games ... television blaring ... dart games ... dart tournaments ...."

"But before that you had disco ...," Betty offered as another reason for the decline of people really listening to music.

Harold continued, "But then suddenly the movie 'Urban Cowboy' came along with John Travolta, and everybody got into Mickey Gilley and Charlie Daniels and there was sort of a resurgence of country music, and country music is still moving in the direction from that movement, I believe ... the forerunners of that have been the Desert Rose Band, etc. But the club scene in Louisville has now turned into ... I guess the best way to put it is that there's no place in Louisville where you can go and sit down and have a drink and really listen to music anymore. And I think it's a real shame."

"Now there are some," Betty interrupted, "but they're the really small jazz and blues rooms."

"Jazz has always had a small but devoted audience," Harold said, "and folk music and bluegrass have always had a small but devoted audience, at least in clubs, but then, on the other hand, you turn around and you have bluegrass festivals where hundreds of thousands of people show up. Now what mystifies me is here we sit, the largest city in Kentucky, and I know this for a fact from playing for 21 years in Louisville, you can be playing at a hotel and someone will come up to you on the break and say 'I didn't know that this kind of music could be heard in Louisville. We have been looking all over town, we've been here for three days on a convention, and we've just now found you, and we're leaving in the morning. But we can't hear any Kentucky music. Where can we go?'

"And I say, 'Well, this is it.' Unless you happen to catch a bluegrass band that's in town doing a one-nighter."

"Some time ago thee was talk of a bluegrass museum here. Bill Monroe and Kentucky Fried Chicken ... I think Kentucky Fried Chicken put $50,000 in an escrow account to get a museum ... and all of a sudden Owensboro grabs the ball and runs with it. And here we are, a metro area of around a million people, and of all the conventins and everything that comes to town, and you can't hear the music that made Kentucky world famous for bluegrass and folk music. It's a mystery to me." (Harold was almost preaching at this point, and I was silently providing the amens.)

"I also have an opinion about that," Betty chimed in. "I think bluegrass type music is more indigenous to the mountains, and I think Louisville is a little bit too ... although it may be an overgrown country town, it is still urban in a sense. And we have a lot of blues and a lot of other music here that has nothing to do with bluegrass, and so Louisville could be like New Orleans ...."

"That's true," Harold agreed, "but I disagree to a certain extent because there are people who have moved here to Louisville from all over the state, all over Indiana, all over Tennessee, and they love that kind of music. I'll bet I have had five or six hundred people in the last ten or fifteen years come up to me and say 'Where can we go and hear some Kentucky music?'"

"They're talking about strings," Betty added.

Again talking about the past success of Louisville's Bluegrass Festival, Harold said, "The problem is that they thought that the bluegrass and the folk music was getting stale ... and I agree with that. But now it seems that they have gone almost in the other direction, and the bluegrass and the folk music has sorta taken a back burner to rhythm and blues and to rock 'n' roll, and to Fifties and Sixties music."

The Cumberlands played the first Bluegrass Festival on the Belvedere in about 1970, Harold said, along with Bill Monroe, John Hartford and one or two other bands.

"After that they hired a quote, consultant, unquote, who helped them put the show together. Well, they didn't ask us to come back because Betty played tambourine. Tambourines have no place in bluegrass music. I'm the first one to agree with that. But we didn't play just bluegrass music, we played folk and a little country stuff too, which is where our meat and potatoes ... that's the kind of band we are. So, therefore, we were never asked to play again, until two years ago. So ... 18-19 years go by and we come back and people liked us. Now what happened to all the time in between? This consultant was doing this picking of the bands and they'd have meetings, etc. But there were so many wonderfully talented people. I'm not just blowing our horn, but a lot of people here _ the Steve Fergusons, the Sam Bushes _ that they wouldn't even talk to, wouldn't even hire."

"For what?," Betty asked her husband. "Bluegrass? Of course not. It was bluegrass then."

"But we were doing some of it," Harold answered back. "There were bluegrass bands that were doing rock 'n' roll tunes with acoustic instruments. So they should have sorta mixed it, but instead they made a great big change and suddenly ... one year I was talking to whoever was booking the thing down there and they said, 'Well, you all are too country for us,' and two weeks later I read in the paper that they had hired Emmylou Harris to be the headliner. Now is that country?"

"All of this _ and it may sound like I'm preaching, but I'm not, but it's just my opinion _ comes with the advent of VCRs, cheap movie rentals, the T.A.P. program, and another generation coming along that grew up on rock 'n' roll, has sorta diminished the club scene to the point now to where a guy is lucky to be able to go out and play a club as a single and make $50 a night. That's what it has boiled down to. And I think it's a crying shame for a metro area of a million people and you can't find one club owner that is willing to say, "... at least 60% ... or 70% of the time we're going to use acoustic type music _ folk, bluegrass or country or Desert Rose-type country, or whatever, and try to build an audience, because there's a market out there for it. But if you take one of the officers of General Electric who has a tour bus full of people from all over the world and he's showing them Louisville, and he calls me at my home on Friday night and says, 'Harold, where can I take these people to hear some music?'

"(And Harold replies) 'I'm sorry, I don't know.'

"Either you love somebody, or you don't love somebody," Harold stated emphatically.

As I drove away from the Thoms' Southern plantation-style home in Eastwood, I saw in my rear-view mirror a couple who obviously love each other. The handsome, distinguished-looking gentleman and his lovely wife were standing on the front porch. Her beautiful, long blonde hair was blowing in the gentle breeze, and she was holding a dachshund named "Shady Grove III."

For booking or other information about the Cumberlands, phone (502) 245-6262.