social bookmarking tools:

|

|

| Available RSS Feeds |

|---|

- Top Picks - Top Picks |

- Today's Music - Today's Music |

- Editor's Blog - Editor's Blog

|

- Articles - Articles

|

Add Louisville Music News' RSS Feed to Your Yahoo!

|

Where the Delta Meets the River City

Bluesman Adam Riggle carries on the Mississippi tradition

Legend has it that blues legend Robert Johnson sold his soul to the devil at the intersection of highways 61 and 49 in Mississippi – in exchange for becoming the greatest blues player ever.

In this Faustian legend, Johnson's desire to become a blues master so motivated him that he would arrange to meet a large black man at that intersection (who allegedly was the devil), hand over his guitar for tuning, and then collect it back, at which point he would possess the playing, singing and songwriting powers he craved. Johnson didn't live long after that (most likely fictional) meeting, poisoned at the age of 27, but he sure did make some influential blues music before paying up on his trade.

Some 75 years later, give or take, another bluesman, Adam Riggle of Louisville, has a slightly different story – but it's no less compelling.

As this legend has it, Riggle was 11 when he talked his father into taking him to the Mississippi Delta to see where his favorite form of the blues was born. Young Riggle was already hooked and was already a pretty darn good blues player at that point.

"I begged him and begged him and begged him," Riggle said. "I wanted to go see Robert Johnson's grave; I wanted to see Sonny Boy (Williamson)'s grave; I wanted to see a real juke joint. I think the real reason he took me down [was because] at the time he repossessed cars, and he had a car he had to get in southern Mississippi. He said, 'OK I'll take you with me.'"

During that trip, his father took him to visit all the requisite sites in Clarksdale, Miss., including one stop that ended up being, well, legendary. "I want to get your picture in front of the Delta Blues Museum playing your guitar," his dad told him. So the young boy pulled out his guitar and started playing.

And that's when contemporary blues master Wesley Jefferson happened to walk up. He was impressed by what he heard from the young man, and invited the Riggles to come out that night to a joint called Smitty's Red Top to hear his band play. Trips to Clarksdale then became a regular thing for the Riggles. By the time Adam was age 13, he was sitting in with Jefferson during his trips to Delta blues country.

Adam Riggle calls his good fortune a "blessing from god" as opposed to a deal with the devil. During his teen-age years, he was fortunate to learn from people like Jefferson, Big Jack Johnson, Terry "Big T" Williams and others. He shared the stage with Sam Carr, Big Jack Johnson, Super Chicken, Jimbo Mathis and T-Model Ford, among others.

And this is the legend of how Riggle became known as "Mississippi Adam Riggle."

"[The nickname] Mississippi Adam Riggle started as kind of a joke," he said. "But ever since I was, like, 13 years old, I started going down there just to soak it up. Somehow, I just made some really good connections down there with some older guys, and that really proved to be a worthwhile thing. I don't know how, we just started hooking up; I would just soak up how they played. Eventually they started calling me up to jam."

Not that he didn't take his lumps – and often he took those lumps in public. Riggle tells the story of sitting in one night as a young teen with Williams.

"He's the man down there," Riggle said. "He used to have me come down and play with him, and he would literally cuss me out in front of all these people. I'm the only white face in the whole club, and he's telling me I can't play worth shit. Then he would take me aside during a break and say, 'Look, I just want you to play my way. It's a Mississippi thing – you ain't In Chicago.'

"It was a nerve-wracking thing, but it taught me a lot about what's real."

Unfortunately, Riggle hasn't been to Clarksdale in about two years, primarily because so many of his mentors have died. "It's an unbelievable loss," he said. "A lot of these people didn't get recorded. Wesley Jefferson didn't get recorded until they found out he was terminally ill."

But that hasn't stopped Riggle and his band from keeping the tradition alive.

BAREFOOT BLUES

Riggle is an organic kind of guy, bereft of pretense. When you think of a Delta bluesman, you think of an elderly black gentleman with worn eyes, a wide hat and a hollow-body guitar, in the vein of David "Honeyboy" Edwards, one of the early Delta blues players who passed away last year.

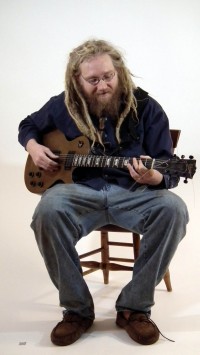

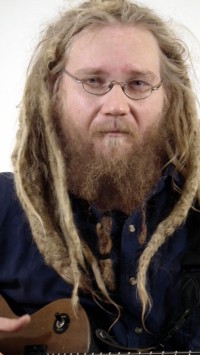

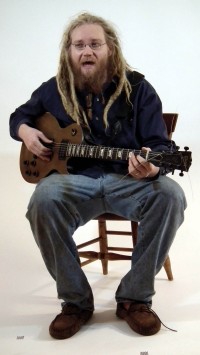

But Riggle wears long dreadlocks wrapped in colorful knit, and likes to perform the blues while barefoot. Add a checkered shirt and a pair of old blue jeans, and what you see with your eye is more like a cross between a hippie and a grunge rocker. But it's the feeling of the blues that drives Riggle.

"You can feel that bass coming up through your feet, man," he said. "You get more into it."

Riggle admits that as a kid he was into hard rock, like Guns 'n' Roses. (Hey, weren't we all?) But then at around age 11, not long before his fateful Delta trip, he heard the album Unplugged by Eric Clapton. That album featured Clapton originals sitting side by side with covers of songs by Johnson, Muddy Waters, Bo Diddley, Big Bill Broonzy and others.

In particular, it was Clapton's cover of Johnson's "Malted Milk" that changed everything for the young Riggle. That's when he dusted off his guitar and really started playing.

"That was the first blues song I ever heard," Riggle said. "That was it for me. It's one of the simplest [songs] in the world, but it's just emotions."

At that point, Riggle began educating himself on the blues, paying special attention to Johnson. "Then, I figured out who influenced him and came across Sun House, and that's when I moved into the grown-up stuff," he said.

When he started playing, it was about as grassroots as one can get. "I would put a CD in and just play along until I could eventually make the same notes," he said.

He progressed quickly, and, naturally, everything changed the day he met Jefferson in Clarksdale.

"When I went there again, he remembered me," Riggle said. "I guess I got my confidence, and sat in with him on stage. Somehow he liked my sound. I don't know how. I think back to those times and think about how good I was and I cringe, because I wasn't. But even then I guess I had some kind of feel for it, or I don't think they would have wasted their time on me."

The feeling is what drives him now – the passion for the music, and the emotion buried at the music's core. That's the blues.

His first band was called the Brickhouse Blues Band. "I was probably 16; my parents wouldn't let me go to bars, so those first two years before I turned 18, we played coffee shops, Books a Million, just stupid little places like that. When I finally turned 18 we started playing at Zena's."

Zena's Cafe, of course, was one of the great blues clubs in Louisville for many years, and was the site of countless blues jams with audiences packed in like sardines. "Playing there was like playing in your living room in front of friends," Riggle said. "Of all the places I've played, I think it had the best acoustics. Just a great sound in there."

The 30-year-old and his band play frequently – every weekend, if at all possible – at places like Hideaway Saloon, Stevie Ray's, Harley's House of Brews (in the former Zena's location) and others.

"They [his bandmates James Warfield and Lenny Popp] get on me all the time when we have big gaps when we're not playing," Riggle said with a chuckle.

But, believe it or not, there was a time when Riggle strayed from his first love and played other types of music in various bands. Often, it was music he didn't really like – or at least music he didn't have a passion for like he does for Delta blues.

"The last band I was in, we were playing great music, but we were going in two different directions," Riggle said of the group Dirty Church Revival. "They wanted to play rock 'n' roll. There once was a time when I was sure I was going to make a lot of money doing what I'm doing; I tried so hard to make it happen like that. I was fighting myself.

"I can fake playing rock 'n' roll or hippie music, or something like that, but what I'm good at is playing the blues, so why not stick with it? When I was trying to play music for a living, I was playing everything – I was in a hippie band called Bucket. We had our shtick. You get good gigs when you dress a certain way and put an image out, but it's all fake."

Riggle credits the late R.L. Burnside, another Mississippi blues singer and player who recorded with the Jon Spencer Blues Explosion and found success in the 1990s.

"When I was trying to make money at [music], I wasn't happy with what I was hearing or what was coming out," Riggle said. "I love Stevie Ray, but that stuff doesn't grab me the way Son House does. I was in Clarksdale at a blues festival when R.L. Burnside was playing. I had never heard of R.L. Burnside, but I fell in love with the blues all over again. It was like that whole thing was just for me."

In fact, that very Burnside performance can be seen as part of You See Me Laughin': The Last of the Hill Country Bluesmen, released by Fat Possum Records in 2005).

"You can see me standing there with my jaw dropped," Riggle said.

BACK TO THE BLUES

And so Riggle decided to play the blues just to be happy, which is ironic in a way.

"I was like, 'Hey, I've got a job – if I just do this for myself, I can enjoy playing music.' I enjoy the people I play with, which is gold."

Another irony Riggle points out is that while the blues is an American art form, it is far more popular outside the United States – he cites the U.K., Canada, Japan and even Sweden as countries that love the blues. While a European tour isn't in the offing, Riggle said he wants to keep playing out of town as much as possible, at the very least.

"I'm trying to get out of town any chance I can get," he said. "You know, there is a quote in the Bible that says a prophet is not respected in his own home town. The same goes for a musician. Being from out of town puts you in a different class."

And he wants to keep playing real, old-time Delta blues as much as possible, rather than re-hashing "popular" blues tunes like "Pride and Joy" or "Mustang Sally.

"People come up and say, 'Will you play "Mustang Sally" or 'Will you play "Pride and Joy," and I say, 'No – we don't do that.' College girls and older people have a convoluted idea of what the blues is; they think it's the Blues Brothers or Stevie Ray."

"Mustang Sally," in fact, is a song Riggle counts as one of his pet peeves: "People shouldn't beat covers into the ground like that."

What motivates him most is the "blues that never made it out of the juke joint," he said. "The reason they played one chord is because they didn't know any other chords. And they didn't need to because they got people up dancing."

His band will throw an original in every few songs, but the goal remains the same – to keep a groove going, and to keep people moving. It doesn't matter if the music is stripped down or raw. It just needs to have the feeling.

"Howling Wolf is raw," he said. "Not some of this stuff in a suit, dressed up and putting on a show. I got dreadlocks down my back. How am I going to put that in a fedora?"

In fact, he is happy to be a walking tribute to "real" blues players. "The reason I play Son House is because I want people to know who that is. I play some of Wesley Jefferson's songs just to keep him with me or to make sure somebody else gets a piece of what he was putting out there before he died. I would say 80 percent of our covers have a reason behind them."

And that reason isn't about making money.

The restaurant cook by day continues his enthusiastic rant with, "F**k it, man. My bass player is a retired truck driver. He don't depend on this to make a living either. It's good to make money doing it, of course, but with that stress [of having to make money] taken off you can have a lot more fun. You don't have to count on all those people coming in the door."

Case in point: Mississippi Adam Riggle and his band released a CD last year called Broke and Hungry and have pledged to donate proceeds to WaterAid, a charity that provides water filters for third-world countries. Yeah, it's not about the money.

No, Riggle just wants to play music, enjoy himself and continue to improve his craft.

"I think the key is to never be satisfied," he said. "Don't ever get to that point. It's mainly about doing what you want to. [It's about] not struggling against yourself to convey whatever is inside of you – I owe 100 percent of that to my band. With these guys I've got, the whole reason we play is for the love of the music we play."

The 11-year-old version of Riggle, playing his guitar in front of the Delta Blues Museum in Clarksdale, Miss., couldn't have said it any better.