social bookmarking tools:

|

|

| Available RSS Feeds |

|---|

- Top Picks - Top Picks |

- Today's Music - Today's Music |

- Editor's Blog - Editor's Blog

|

- Articles - Articles

|

Add Louisville Music News' RSS Feed to Your Yahoo!

|

A Look At Domani

By Bob Bahr

They are not jerks about it, but Domani is a band that won't let you pin them down. Everything about the Louisville rock quintet is open, even vague. Ask the young MCA recording artists about the meaning of the band's name and they'll answer, "Good question." Ask them their plans and they'll individually voice the same ambiguity, "Just keep playing out and having fun." Challenge them to categorize their music and they'll squirm, like they have undoubtedly squirmed in MCA's boardrooms and then slowly cite virtually every type of music known to the Western World.

Hear Domani live and try to peg their sound. Folk? Country rock? southern rock? Gospel?

Who's that I hear influencing their sound? Elton John? Bruce Springsteen? Miles Davis? Glen Frey? B.B. King?

Up close, Domani seems like a sprawling, disorganized musical mishmash. From the back of the bar or your listening chair, the band sounds like the next big musical movement. Reality is somewhere in between.

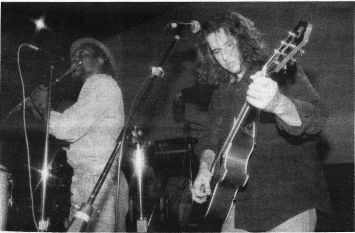

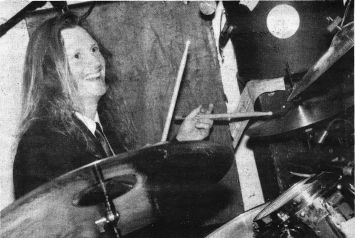

The blurriness comes from the subtle workings within the band, the vastly different interests and input of the band members. Drummer Stuart Johnson is the rock-solid jazz explorer. Rhythm guitarist John Bajandas is the immensely gifted lyricist. Pianist Todd Smith is the traditional music fiend, a lifelong musician and multi-instrumentalist. Sam Anderson is the imposing bass player, a scene-stealing powerhouse soul vocalist. And guitarist] vocalist Todd Johnson is the frontman with rare elegance and style. The varied characters add up to make a great rock band, the kind you sit down and listen to. The kind with depth and feeling and spirituality.

The spirituality of Domani seems to be what touches the audience, more than their comfortable, capable brand of "rock with heavy folk leanings." A lot of Domani's spiritual feel comes from their lyrics — poetic, sometimes abstruse ventures into human moods and feelings. All the band members contribute songs to the effort, with the primary responsibility falling on Bajandas and Todd Smith. And accordingly, every member of the band puts forth an aura of spirituality, even if it's hidden behind the wild-eyed persona of Stuart Johnson. It's not a religious fervor, but rather a looking past the mundane. Domani's lyrics and music deal with equality, love, injustice, 'and other large themes. No ditties about cars and girls here, although the band would undoubtedly tell you that they COULD write a song about cars and girls. No sense closing the door on any possibilities.

Theirs is a dangerous double-hook, with sweet music capturing you, then thoughtful, almost wise lyrics snagging you for good, turning you into a bona fide Domani follower. Hear "The Innocent Years" live and you'll understand it. Prick your ears to catch Bajanda's words in "Train Bound for Morning":

I spoke to the woman they call Janie

She had the smile of an angel. so fine

She said, "Honey if you got the time,

Would you mind standing with me in

the bread line?

"Can you see I'm truly trying

Could you help me board the train bound for morning?

The chorus simply states the message:

You see I believe in tomorrow,

my friend Just as sure as I may die right now

Come morning I may come alive again

Come on, you can take my hand

You lead me and I lead you

Together we'll someday understand.

And while the music Domani drapes around these lyrics is simply gorgeous, the lyrics shine through and the message works its way into your consciousness. That' s why the front third of the area in front of the Red Barn stage was filled with occupied chairs one recent Saturday. Those rapt listeners weren't dancing, although they probably were tapping their foot. They gazed, smiling appreciatively at their hosts, Domani and they looked as if they were attending the best church service of their lives. I'm not philosopher, nor a sociologist, but the way things go down at a Domani show looks an awful lot like people finding spirituality in music

Todd Smith and John Bajandas talked to me for a couple hours one day at Another Place Sandwich Shop, telling me about the band and their opinions on music as an art form. Smith and Bajandas described the band as a very democratic entity, with all the freedom and difficulties inherent in a democracy.

"The only strange thing about it is when it gets to the writing process," said Bajandas.

"It's always very strange to release a song into the band and all these different things envelop it. Some of the musical tastes are so varied that some of the songs kind of hit strange. We may write something so to the folk side, then when it comes to people who think way different from that, they go kggreegh! When you start mixing all that stuff, some things work and some things don't. A lot of songs we've had didn't really cut it all the way down the line into the sound of the band. They were like, 'That's a little too much of this.' It gets way out, left and right. And those songs kind of trickle out, eventually," he said.

"I think a lot of [that diversity] comes through live," Bajandas said. "There's a lot more spontaneous things and a lot of that just comes out of your head. When you get going, a lot more of your influences come out, I think. Everybody would have a completely different list of influences."

"And that just makes it interesting," Smith interjected.

Todd and John were in no hurry to sketch their bandmates' musical influences. They didn't seem to feel comfortable speaking for Todd Johnson, Stuart and Sam. In fact, they didn't seem comfortable talking about them at all without them present.

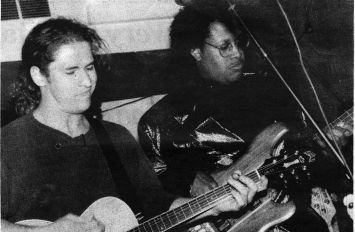

From what I could gather, bassist Sam Anderson brings an open mind into the band as primary asset number one. He had to have an open mind, because rock was fairly new to him when he joined Domani. He didn't grow up listening to rock, so he doesn't have preconceived notions about how it should sound, or whether it is derivative. Instead, Sam was into Otis Redding, Sly Stone, Billy Preston. And Sam knows a good song when he hears one.

John Bajandas is more interested in songwriting. Bob Dylan and Van Morrison are big influences, but he also professes a love for Hank Williams Sr. and Bob Wills & the Texas Playboys. John's acoustic guitar, when the sound man is kind, gives Domani a root in folk.

Todd Smith echoes that love for quality songs. He says he feels closest to Van Morrison and he loves European instrumentation, the use of pianos, flutes, mandolins and other traditional instruments.

The rock 'n' roll roughness and energy comes from Sam and Stuart, a strange turn of events considering Stuart is heavy into jazz and Sam is steeped in gospel. Nevertheless, Sam's bigger-than-a-house voice pushes the band to a new energy level and Stuart's drumming is heavy on the beat and prominent. Stuart talks excitedly about Miles and John Coltrane, people who pushed the boundaries of their art form.

"Being on that verge is probably the most characteristic thing about this band," smiled Bajandas. "Being on that edge of something being too much. there's always been a tension in there, about all these different kinds of things. I think that tension is what makes it good,' and it also makes it very difficult. That tension leads to everything that's good and bad" Bajandas said.

"Every time Todd picks up the mandolin, somebody in the band might go, 'Oh god.' Some of the songs even go more like jazz. So it's weird. It's like we've got a blues thing going on and a folk thing going on … we've got a traditional thing going one way and more like a jazz-dissonant thing going the other way. It goes all over the place. But I think the best songs have a little bit of everything," said Bajandas.

"Dove" perfectly demonstrates how these varying, styles are reconciled. Starting off with Todd Johnson and Sam Anderson playing a line in unison, "Dove" then takes off on a blue-eyed soul excursion, with Todd's country-tainted vocals delivering the plea for peace and understanding. The song gathers steam with every chorus, finally breaking down into a chant of "brothers and sisters," with Stuart laying down a jazzy beat on the inner bell of his ride cymbal. Then a boogie beat emerges and Sam funks it up. Todd Johnson demonstrates his mastery of guitar effects, picking up an Allman Brothers feel, then a David Gilmour sound. Finally, Stuart smacks his set hard on all four beats and Domani briefly sounds like an astute hard-rock band.

"Oh man, I love that song," said Anderson with characteristic enthusiasm. "When 'Dove' comes up, it's like, 'Now fellas, we've done our job. Now is the time for US to get off,"' Anderson explained.

Sam Anderson's role in Domani is fascinating. An indefatigable player, Sam wishes Domani would play all night. He and Stuart both fantasize about it, but it's a long-shot considering that Domani usually plays only one long set on a typical gig. Sam picks up the slack with outside jobs with danny flanigan, Curtis &. the Kicks and virtually anybody else who'll have him. Any band would benefit from his outstanding electric bass playing and soulful vocal shouting and nearly every band would disappear in the shadow of the big man. Even Domani sometimes seems in danger of becoming a backing band for "the Sammy Show," as one band member put it.

"I hear it all the time and I honestly don't believe it," Sam argued. "I don't believe I have that much of an effect on the group. My religious beliefs, my beliefs affect me period. I am that person. I believe in Christianity. If I could be the perfect Christian, then I would. My atonement, my blessing and everything is wrapped up in it and it comes out in my playing.

"When I was little, I played with so many great musicians ... in church, there were just so many great musicians. And you just go and just cut loose. I grew up that the preacher would start a song off, then somebody else would sing a verse and then the preacher would say, 'Sammy, I want you to take a verse.' And after a while, it just got to the point were there was nothing that I didn't take part in. And when I did [participate] you give all you have. You don't hold back anything, you submerge yourself into what ever it is that you're a part of. In that sense, [my faith] does affect my playing and the band," Anderson said.

Anderson's impact is felt on nearly every song, especially the last quarter of it, when he brings his husky back-up vocals to the front and soulfully free-styles away. It may sound formulaic and sometimes he does seem to enter songs on cue, but one soon realizes that Sam just can't hold back any longer. That's when the audience smiles bigger and Sam makes weird, impassioned faces. He calls for a witness. He shakes his head. He wails. He bows his head. The band rides his emotion. The song ends with Sam jumping up high" with a decently executed mid-air leg split.

Sam has a big personality, but "he's not overbearing. In fact, it's impossible not to like him, once you realize the humility and amazing grace in him. Anderson toured with the nationally acclaimed gospel group the Winans and he has played dates with Earth, Wind & Fire. But Sam has all this in humble perspective.

"I don't want to be the one to sound all heavy and everything, because I'm not," he said. "I'm. just a country musician from Louisville, Kentucky. Not country in the sense of country music, but country in the sense that I'm not real sharp. You know, I'm not a city slicker, or the most intelligent cat in the world. There's a purpose for everything I'm doing, but I don't go up on stage going, 'What's my purpose here?' I don't even think about it, when I go up on stage," Sam said.

"Just about everything in my life that made any kind of change has been because of music," he went on. "So I have to recognize [music] as the strongest political tool that I can use at my disposal. The way I received that particular revelation is, people have come to me at different points after something went on. After a show went on, their lives were touched, or they heard a particular song. More so, to be honest, my life is about that. It's about touching people. My direct motive is to reach somebody and to be a strong influence in a positive direction. So consequently I play wherever I can. Wherever people need joy," Anderson said with simple conviction.

The five members of Domani hold different views of the "whys" of creating music. For some, it is pure artistic release. For others, it is an attempt to communicate and connect with the audience. For all, the process is introspective, as their thoughtful comments reveal.

Bajandas took a crack at it, "The purpose of [creating music] is on two levels: 1) it's a personal expression and 2) on another level, there's a universal thing that I think people want to happen, whether they admit it or not. To me, that's really positive. I don't think the clearest thing is necessarily the best. Sometimes it's not. But I do think that it is important to me to have it relate. You write a song because you feel it. When I'm writing, I don't think, 'Now is somebody else going to get this?' But hopefully, if I'm lucky enough and observant enough of a certain subject, my observation is something that is common to more than myself.

"I think folk music is like that. Like a Hank Williams song that has become a standard, originally it was one guy sitting there playing it in a room. When it gets interesting for me is when someone tries to make something. I think folk music is an attempt to make something that is universal, that's simple and the subject is simple. It's an intention, like Hank Williams, to write songs that are very simple, that a 60-year-old man would get and a young kid would get, on completely different levels. I think [Bob] Dylan tried to exercise that a lot, the universal. One of my favorite songs by him is 'Boots of Spanish Leather.' That song for me is a complete attempt to touch the universal, to tell a tale that happens over and over," said Bajandas. "It has the feeling of being a hundred years old. It's got that vibe, you know?"

Bajandas' lyrics are enigmatic and poetic. They stray away from realism and find refuge in wise simplicity. "John writes in parables," Todd Johnson commented. Indeed, many of his songs deliver an uplifting message, or at least offer comfort. "Body Into Soul" mixes the abstract with concrete images; it would be at home in a book of poems. The chorus:

She walks the miles, only to find

Heaven and hell can be bought or sold

But only the miners' hands know the price

of that gold

And on a good, good day we feel we may never grow old

Many a lover, many a friend

Turning body into soul.

"I don't think [about the listener's perception] when I'm writing it, but after the fact, when somebody says something about such and such line I know, because I'm a fan of other writers and I know that a line that [the author] might not have even known what it meant could mean something to someone else," Bajandas said. "That's the power I 'm talking about, more of the transfer of some of these arts to the audience. But I don't think that's a conscious decision on the part of the artist to do that," he said.

"People relate to the songs you write, but it's not necessarily what you meant when you wrote the song," Bajandas continued. "There's a song called 'Momma's Song,' it's about a feeling related to your past generations that have walked on the same land. There's a mother talking to this child, saying, 'See where you walk? There are others who have walked there before you and they are with you.' This one girl came up to me and she said, 'That's an anti-abortion song.' It's weird. You definitely. have no control. I think that's understood. I never really try to explain what something is fully about. I think it's much more interesting to let somebody else think up their own explanation."

Todd Smith said he takes a different view. Smith is a bit less giving to the listener and ironically, his songs and his musical contribution are more pop oriented. One gets used to the contradictions in Domani.

"I think the purpose of art is for the artist," Smith began. "Art exists as a result of the artist's need to express whatever it is that comes out and becomes art. That's why art exists, as an expression of the artist. If that touches us ... that's why we speak of artists and poets as spokesmen, voices of a generation or a culture. They grew out of that culture or generation and they are a part of it, so their expression reflects it. And if they are really in touch with it, then [their art] will be on the pulse of that culture and people will relate to it. And it will become popular, or whatever. I think art is a selfish thing and I don't mean that with a negative connotation. Art is selfish and it's for the artist. The fact that people like it, or relate to it, or derive some benefit from it — that's a result, a side effect, a fringe. In my opinion, it's not the purpose of art to relate to other people. The painter, he paints to express whatever he sees and how he sees it. Then he gives it to the world. I think there is something in every artist that drives them to want to share their vision with the world," he said. "And that's why we play our songs to people.

"I'm very concerned with expressing big truths of feeling, or whatever it is that is driving me to put the words down. I want to make it real, to bring it to the real world. I want it to be true to the feeling or whatever it is that is compelling me to write. The problem is, things can get lost ir1 the translation. We [Todd and John] are both concerned with expressing a feeling. I am not concerned with how it is taken. I just want it to be true to myself. I don't want to put something down on paper and have it come across as one thing, when I feel something else. I want it to say what I want it to say," Smith concluded.

The brothers Johnson concurred. "There's a sense of release in writing a song, whether it gets recorded or not," Todd said. "I think it's for the artist. I guess you do try to consider what the audience hears, but I think [a song] could be valid because I wrote it, it's important to me and I'm a member of the human race. I think a big problem in music today is it's written with other people in mind. A lot of people don't even listen to the radio," Todd said.

Todd believes in a sort of modified theory of niche marketing. He said he believes that there is a style of music for every kind of person, it's just a matter of connecting the two. Johnson obviously had Domani in mind. At a recent Domani show at Dutch's Tavern, a friend remarked to me as he was leaving, "They're great, but my brother and I were talking and we can't imagine what radio station they would be played on."

That kind of talk does come to mind when you hear Domani's medium-to-slow-tempo tunes. Moving and effective as they may be, it's hard to imagine them on a rock station like WQMF. Domani ballads are more suited to public radio's eclectic shows.

Songs such as "Mountains" and "Cathedral" fit a little bit more comfortably into the confines of contemporary radio, but what's a general manager to do when Domani goes acoustic, singing an Alice Walker poem titled "Songless" in gospel harmonies? Where would the style-jumping "Dove" get pigeonholed?

Of course, notable artists aren't easily packaged. It's one of the things that makes them notable. Domani is asking the world to rethink the present confines of popular music. It's not a revolution, just a loosening of the constricting bonds.

The band has dealt with its own sprawling stylistic breadth at length. The issue came to a head when the band was signed to do a record with MCA. A record almost demands stylistic focus. For the monolithic record companies, a record is a product that must be marketed. And that means the product must be consistent.

"As in anything that is so diverse, with so many people, communication can be a problem," Bajandas said. "It's like, where the line is. How much jazz am I going to accept, when I don't really think it should be there and how much folk is Todd [Johnson] or Stuart going to accept when he may not … the hardest thing about it is finding the common center. When certain people are writing, it becomes very hard to have a boundary on that. And I think live is very open; the boundaries are very open.

"But when you go to record a demo, or you go to do a record, or even go to have a discussion about it among the band members, the language really [limits you]. I mean, I may love what Todd, the guitar player, did at the show and if I say, 'well, I really like that,' he may be thinking about something totally different [for the task at hand]. It's very easy when you don't have to discuss it, when you're playing live and whatever happens happens and it's just fun. It doesn't have to be defined at all. When you try to contain it, it becomes most difficult," Bajandas said with a tight smile.

And that brought up the question of compromise. When is a compromise artistically compromising? What did Domani lose when it was signed by one of the biggest record labels in the world? It gained a shot at enormous success, a chance to have an audience of millions. But what was the price? How can this almost painfully artistic band deal with being a product?

"It's common to think that working under the constraints of something means less quality," Bajandas said. "I completely disagree with that. I think you can present something in a certain manner and still present what you want to present. I think artists are doing that. I mean, R.E.M. and Tom Petty — the songs that they are getting popular by are very simply done, straightforward songs. They're working within the constraints of a major company and that's the way they choose to do it.

They choose to work within those constraints and the music is no less quality than anything else. Like that song, "Learning to Fly," is very simply done and it's a great song. That's kind of like the beauty of it, you know," he said.

"It forces you to refine what you're doing," Todd joined in. "It forces you to distill it to its barest essence. Like in our live shows, you might get the essence of what we are and a whole lot more. Fringe. But you can't do all that on record. It forces you to zero in [on the essence]. It's a positive thing as far as I'm concerned," Smith asserted.

"Being involved with a record company; doesn't really alter us," Bajandas picked up the conversational thread again. "We were doing what we were doing before we signed and we are still doing it. The ways that it's changed it may be that in certain ways? we've refined it. Just like you must paint something in order to present it. Unfortunately, that's true, unfortunately, we don't have the ability of making a complete two-and-one-half-hour live record. ' Not that that would be best. It's just that we can't present it all. Like a painter in a gallery, there's only so much space on the wall. Even though you would hope to have everything and that the people who came to see you would look at everything and make some sort of sense of it. It's hard to make sense of it. An album is a contained attempt to present something," Bajandas said, then took a break.

"It's like the difference between living alone and living with somebody," Smith picked it back up. "We're in a relationship and they've invested in us and we need to work together. It's basically just less self-indulgent. I mean if we were left to our own devices, we would just go off to whatever extreme, which would satisfy us. But we're in a relationship with a company. So that basically means that we have to do what we do within certain broad guidelines."

Could their vision have found a more hospitable home with an indie? "I think it's just another option to go with an independent label or whatever," Bajandas countered. "It's all just options. All of them require different types of attitude. I don't think one's any more ethical or true to the music than another. Music is music. I think it's very dangerous to consider that whatever type [of music] is popular to be the true form. Going alternative, in this stage of the game, 1991, may be ... it was like, that was where all the freedom was. I think quality can be applied to anything. If you really have vision for something and you do it, whether it's on TV or on a big screen or on a record, it's going to be what it is."

I had the chance to hear some Domani demos and the sound, while undeniably Domani-like, varied considerably from their live sound. Smith and Bajandas readily agree to this judgment, although again, they consider that positive.

Said Todd, "Our live shows, we sort of go in and out of hitting it, you know? The whole show is a continuous process of chasing it d0wn, then it clicks for a little while. It goes up and down. When the band is on, when we hit it, our live shows are great. What we do with the songs live, when we hit it, I think it's totally awesome. I think it's very powerful when everybody's on it. We don't always hit it, but we're always fishing for it. It's just that it's a less restrictive medium, you can take as much time as you want …

John interrupted, "There's more improvisation. We leave that option open; a lot of bands don't even leave that option open. A lot of times [the improvisation] is overkill and a lot of times it's not so great, but it's like that option is always open. I think everybody enjoys playing that way. I think that eventually, those two things will mesh, that the live show and our recorded stuff will get closer. We're not good enough at recording yet to be able to do all that. I think it's an art in itself, to try to get something across on tape."

Todd: "And we're rookies."

Domani may be rookies in the world of recording albums, but the band has already done their homework. The band began as a songwriting project started by Stuart and Todd Johnson and John Bajandas. "I considered it very important to have the material before having the band," said John. "I think going the other way is kind of strange." The three moved to New York City in 1987 "to find out who we were as people and what we had to say,"according to Stuart. They explored different ways to approach songwriting, creating their music with John and Todd on acoustic guitars and Stuart on congas. Stuart dubbed the project "Domani," an Italian word that means tomorrow. From the start, the outlook was positive.

The three took on the task of living in Manhattan, the land of $1000-a-month flats and incessant taxi horn honking. They found work in restaurants and Stuart worked as a bike messenger for a while, "until his bike got stolen from right outside a building where he was making a delivery," said Bajandas.

Stuart also worked occasionally as a member of the Hard Rock Cafe's house band, playing holiday bashes and other special events. They found time to write songs, sometimes by planning extended vacations to isolated spots, such as a log cabin in New Jersey. 'When it came time to put together a band, the three knew they needed to make a move.

"Trying to do it in New York is. really hard," Bajandas explained. "first of all, it's hard to find people ... you can find them up there, but it's so hard to live up there. It's hard to rehearse, hard to get in tune with the kind of people you're working with. We got; back here, for one thing, for financial reasons, so we could rehearse all the time, and have people who weren't committed to a lot of things. Up there, you're lucky if you rehearse once or twice a week, if you gotta pay for the rehearsal space. We knew people who played here and we knew there were great musicians here. Plus it was just good you know, sort of a hometown thing," he said.

They moved back to Louisville in 1989 and started producing demos. That's how they met the last two members of Domani, Todd Smith and Sam.

"It seems like me and Sam just sort of crossed paths with the three of them right about the time that they were thinking about expanding," Smith remembered. "There weren't any ads saying 'Keyboardist wanted, bass player wanted.' They were starting to think about it, looking around with one eye, and we just crossed paths. It really happened by itself."

Smith was running a recording studio at the time and Domani had booked time there. Also recording at the same time was a band called the Gospel Starlites, a Louisville band with a bass player named Sam Anderson. Todd Smith introduced Domani to Sam and that's all it took.

"Sam is always interested in getting into everything he can," Todd laughed. "He said something like, 'Oh, I play bass man! Let me sit in with you."'

The three original members were ready to round out the band. "Once there was a positive idea about how a band would sound, we started to form the idea of what the band would be like," Bajandas said. "The music before had layers of what each member would bring. We didn't go out looking for people; they just kind of fell into place. They represented things that were already in the music. Then they took it and made it their own."

The newly recruited members had little time to adjust. Domani was soon tapped for the opening slot for RCA recording artist Grayson Hugh.

"We started rehearsing here in Louisville and we got an offer to do a warm-up spot on a tour for a few weeks before we had played any gigs," John said. "So we rehearsed for that. It was cool. Through our management, we just sort of fell into that. The first gigs we ever did were all original and it was an open audience. I mean, it was really cool. We were pretty rough back then, but we always got a really good response [from the audience]. So I think there was always something there, even when we were pretty rough. I think the songs were pretty strong and that came across."

Domani's approach to forming a band – getting down strong original material first – had already paid off. Domani was never known as a cover band, so there were never any preconceptions. The cryptic band name also helped avoid harmful categorization. And the band's trial by fire on the RCA tour started them off on a good foot.

"I think we got good, playing every night," Smith said. "We went out two weeks, then we went for three more weeks. It wasn't straight; I think it was scattered. I think we played about 20 shows. I think that's where the whole thing got momentum. If we would have been around here and played every couple of weeks, I don't know if it would have ever got off the ground," he said.

"After the tours, we were something," Smith continued. "We were an entity. We had accomplished something; we had something to stand on. It was like, 'Okay, we did a tour, now let's do something else.'" The next thing was recording. The material was already there and the musicians were meshing well together. Somewhere along the line, the decision was made to keep the songwriting at the front. The music changed considerably, but the melody and lyrics remained on center stage. Even now, Domani sets are frequently broken up by acoustic renditions that spotlight the songwriting. The approach is not affectation; remember, this band started out acoustic. John Bajandas still plays the melody on his acoustic guitar the same way it sounded when the song was conceived. In some cases, the chord progression changed when the song was adapted to the whole band. Other times, John's acoustic playing duplicates what the band now does. The band is quite obvious about their acoustic numbers. The whole band lines up across the stage for a bluegrass/gospel harmony effect. The intimate setting is captured on Domani's demo recordings.

"We made our first demo tape as a band about halfway through that [RCA] tour. When we had time off, we went to Nashville and made a three-song demo tape," Smith said. The band was now faced with the restrictions of recording. Domani was already a force to consider on a live stage. Sam's incredible energy, the band's acoustic intimacy, the musicians' penchant fir exploring — how could it be captured?

The answer? Domani doesn't even try.

"I think this band is best live," Bajandas admitted." But on an album, you make a concise statement. You could go on with a melody and a tune forever and maybe someday we'll write 20-minute songs, but at this point, [we work] within the framework going on."

Domani had come to peace with their own limitations. But forces within the band ensure that Domani will always press on.

"There's going to be a time when we will be taking more creative risks," Stuart declared. "If you're an artist. you need to express as true as you can. When artists push [their craft], that's when new worlds open up."

Although Stuart sometimes seems to be odd man out, he said he is willing to stick with Domani. "I'm still here," he said steadily. "There's still a little corner in the band for me to fill with my fire. MCA seems to understand what this band is about. And I'm willing to take my risk and sacrifice in my career right now. A lot of people don't ever get the chance to be on a major label. So I'll jump on it and see where it takes us." Even more assuring than the drummer's words is the look of release on his face when the band performs "Cathedral." There is obviously much for Smart to still relish in Domani.

Domani at times seems a bit unsettled on the issue of the band being a commercial entity. Their album has been held up until some new cuts are recorded. The record company is probably looking for new songs that are a bit more commercial. The band will halfheartedly recognize that fact, although they refuse to approach additional recording with a commercial mindset.

"They would like us to record a couple more songs," admitted Todd Johnson. "But they want it to be a natural step for the band. They want it to be the band's style."

"Making it more accessible can be in the producing," John added. "Like what Jeff Lynne did with Tom Petty's new stuff."

Domani didn't get Lynne for the production job. They got Glyn Johns, THE Glyn Johns. The one who has produced the Who, The Rolling Stones, Eric Clapton, Traffic and Led Zeppelin. How did Domani land Johns as their producer? – "It was surprisingly simple," Smith told me. "MCA threw out his name as a good person to do it. Our A&R person, Teresa Ensenat, just sent him a tape and asked him, 'This is a band we just signed and we're getting ready to make a record. Would you be interested in producing them?' And he liked the tape and he said, 'Yeah, I would."'

The choice was popular with the whole band. "Glyn Johns looks at music in an overall sense," Todd Johnson said. "He thinks a song should breathe."

Johns and Teresa Ensenat are two good reasons why Domani is where they are now. One gets the sense that if their music had been handled in a less sensitive way, the band would have faced a crisis.

"We have a really good A&R person," Bajandas said. "[Ensenat] is probably one of the easiest persons to get along with. I mean, I've met some people that I could tell would be really strict. She really doesn't say anything aside from helping out on song selection. She helped really, not in the songwriting or Stuart Johnson, D01 direction, but she helps us to gather the material for the record. Decide on material for the record. More of an objective viewpoint on how to make a cohesive record, how. to make it so people can listen to it and say, 'Okay, now I have an idea of what this band is.' She never gave us direction" on" the songwriting. Once we got down to the final cut, she said, 'Well, it would be good to have such and such song on there.' "I think she's really a song person," he continued. "She pays attention to songs. She realizes that for a band to make a record, there's has to be a vibe going. It can't just be a collection of singles. A real album has a feel, you know? So we're really lucky in that respect. Especially for a band like us, who doesn't have a direction, really. Most people would panic and tell us exactly what to do. She only came into the studio a few times. She was always like, 'Great. Keep going."'

Ensenat has created a homey enclave in what could have been a cold, unsympathetic corporation. "These companies are trying to ... they're not really open to something that's not ultimately just enjoyable to listen to, or entertaining," Bajandas said.

Does that mean that the days of Dylan are over?

"I don't think they're gone," he said. "I think if somebody like Dylan comes along and somebody thinks they can market it, it'll happen. But I mean it has to be those two things together. It's very difficult (I'm not going to say it's impossible) for someone like Dylan to exist only on the merit of his songwriting. Somebody has to think, 'I can make money with this.' And that's the bottom line. I get that feeling pretty much 100% from the major labels."

Smith's song "The Offering" lends its name to Domani's upcoming MCA release. His song has the speaker offering a helping hand, a hand to liberate and support a burdened soul. It's a perfect analogy for the band. Domani's music is meant to uplift. "In this band, I think it's sort of taken for granted, but we're very concerned with provoking feeling," Bajandas said. "I don't think there's one song we do that doesn't deal with that. Sometimes it's happy feelings, sometimes it's sad and other feelings are very difficult to understand. Some are on a very minute scale, like day-to-day. Other songs deal with concepts that are like, huge."

Every band member offers their musical abilities and interests. And they offer their own songs. While the songwriting responsibility lies largely on Smith and Bajandas, everyone contributes tunes.

' Bajandas said, "There are writers in every member of the band. But when the publishing company says, 'We need one more tune,' I think they direct it toward me and Todd [Smith]. I always liken it to a merry-go-round. Certain people push all the time and certain people choose when they want go push and they push. We appreciate the help; But if you were to say, 'who is pushing it the entire time,' there ARE certain people pushing it the entire time. That end of it is very cool, though. There's no tension really. If somebody has a good song, we all want to do it, because we all want to have good songs. It's very Todd Johnson concerns himself more with the instrumental part of songs. "With me; it's not so much an active songwriting thing. It's hard work for me to write songs," Johnson said. His brother Stuart, on the other hand, finds considerable release in writing songs.

"For me, personally, it's 80% release," Stuart said. "Obviously, you are trying to communicate something with a song. But if I feel something, I get it out. It's very gratifying on the personal level."

The drummer said that his songs are "different," lyrically and musically. While he is passionate about his profession, Stuart understands the art of compromise.

"We all sort of agreed that if a song doesn't have the Domani feel, then we don't do it. Even the harder-edged stuff still strikes a certain chord in it that is Domani," Johnson said.

Sam Anderson's song contribution is a story in itself. Domani sometimes closes their set with Sam performing "Lighthouse" all by himself on the stage. But the song originally wasn't a Domani song.

"'Lighthouse'? The funny thing is, I wrote the song ... I went through a lot of changes," Anderson began. "I raised a little boy for five years and thought it was my child. I found out in January that he wasn't. I went through all kinds of stuff. I went through court, child support all kinds of stuff, for five years. People threatening to lock me up, throw me fin jail, all kinds of changes. The girl, I was trying to make things work out. And then coming home and being a poor musician again after having some success on the road … 'Lighthouse' came about, just one night. I thought, One day, I' m gonna be out of this. ' I keep trying to look up and say, 'I have to be positive about this. ' Domani was happening and I was trying to say, 'Look at Domani, focus on the good things happening.' And I couldn't, man. And somewhere in there, that tune came about.

"When it was originally written, I intended to give it to somebody else," he said. "I had no intentions of doing it with the band. The band had no intentions of doing it. But I did it one night at a show and this girl came up and I normally sing 'Amazing Grace' for her. I sang that tune ['Lighthouse'] and she enjoyed it, she started crying and stuff and we started talking and I started to do that song at the end of our shows. I thought it would be a great way to end the show. It's a positive tune. It's a song for me, it's a song about faith. I was expounding on faith. Trying to find out where I was in my life. Looking at things and thinking sooner or later it's gonna break. Sooner or later it's gonna happen.'

"I was going to demo it and send it to Ray Charles, or somebody like that. Joe Cocker. I played on the piano and sang it into a raggedy tape player. But I knew this guy in New York and he said, 'Man, let's get up here. We can demo it. I know Joe Cocker will take it,' "Sam said.

"But when the band put together their songlists, most everybody had 'Lighthouse' on their lists for the album," he said, still surprised.

Everybody had it on their list but Sam.

Even when he finally agreed, he thought the entire band would do the song. They thought it should be just Sam and piano, to close out the album. But when Sam and Domani went to LA., John urged Sam to play the song for their producer, Glyn Johns, at the end of a pre-production session.

"So I played it for him," Anderson recounted. "I played it raw, I think I was hoarse that day. Glyn Johns walked up and said, 'That's going to be on the album.' He loved it. I had some faith in it then. But before that, I didn't."

Faith is the key word for the release of Domani's album. It will come out, rest assured.

But no one knows when.

"Another reason the album got pushed back was because we recorded at an odd time and got finished at an odd time," Bajandas said. "They don't usually release new bands after September because of Christmas. Everybody in the world is releasing an album around then. They'll wait till next year to release it. So we've got time. The whole idea is to leave it open-ended and hopefully we'1l have a couple more songs to choose from.

"It hasn't even been slated, really. That depends on what happens next year. It could be March, could be later than that. There-are a lot of factors, like how many other albums MCA is releasing that week, or in that time period. How many other records of similar bands, how much money have they spent in that [financial] quarter. It's all factored in to when the optimal time would be to release the record. We have a very good A&R person, but it's a very corporate thing. Big record companies are very bureaucratic and compartmentalized. We work closely with the A&R department, but as far as the rest of the company is concerned, we're just a line on a ledger. Teresa knows that and she's going to work it to where we will get the best shot, where we can maximize our resources at the record company. So it's not just when the record's ready. There are industry and record company reasons to consider. So it'll be out in l994," Bajandas joked.

Domani has already done yeoman's work on the album. They've been writing songs for it for over three years, recording it for over nine months and anticipating it for forever. One bottleneck was deciding which songs to include, from their fairly large repertoire.

"It was very weird. You go through this thing like, 'Oh, man, you mean this isn't going to be on there?' The whole time, you think, 'That's going to be on there for sure.' -hen when you sit down to write out your list, you realize you have about 17 songs that HAVE to be on the record," Smith laughed.

Once the number of songs was narrowed down, Domani entered the Los Angeles studio and recorded 15 songs and mixed down 12 of them. The experience won't soon be forgotten.

"It was great," said Todd. "It was a really nice studio and we worked with great people. We had a great producer and a great engineer. There were hard times involved, but it was a blast. A great learning experience."

"It was more than anything a learning experience," John agreed. "We had never done anything like that before, so we were kind of all … didn't know what to expect. A lot of the times, we were completely baffled by the whole thing. A lot of times we were just ... [he laughed]. There were some pretty big people coming in there.

"You'd pull into the parking lot and there would be a sign telling who is recording there," Smith continued. "There were a lot of recording rooms and you'd walk around there'd be people like the Black Crowes, Lyle Lovett, John Hiatt."

"John Hiatt came in and listened to us record a few songs," John added proudly.

"Just, a lot of big name producers," Todd said. "Names you see on the back of your records. It was cool that we were working right there with them."

Domani was out on the West Coast recording for over three months and very little of their time was spent on recreation. "We spent a lot of time in the studio," Smith said. "We'd go to the studio at 9 or 10 o'clock in the morning. Come home at 9 or 10 at night, have dinner and go to sleep, do it again."

The band is planning on having a video made, as soon as they pick a single to release. Album art and the video will be done by the same artists to give the band a feeling of visual continuity. Bajandas said they have already picked out the man for the job, a New York artist named Glen Ehrler. In keeping with the laid-back, tasteful Domani approach, the video will probably feature black-and-white images moving with a slow-motion effect. The band is considering using Louisville scenes and places, possibly things from all over the state. "It won't be the rapid-fire things-flashing-really-fast kind of video. It be slower, more poetic," John said. "His eye is very good. The images that he picks are just amazing."

Understandably, everyone in Domani is excited about their MCA album. But the band already has the fever for the road.

"When this record gets out, hopefully we'll be able to get out and open for somebody on a good tour and play in front of people," John said. "Nobody's really heard the band, except for in a few cities in the South. That's the most interesting thing I can think of. Just to get out and have people that have never heard us before [hear us]. Because they are not going to have any you know, play to people who are completely open and want to hear good music."