social bookmarking tools:

|

|

| Available RSS Feeds |

|---|

- Top Picks - Top Picks |

- Today's Music - Today's Music |

- Editor's Blog - Editor's Blog

|

- Articles - Articles

|

Add Louisville Music News' RSS Feed to Your Yahoo!

|

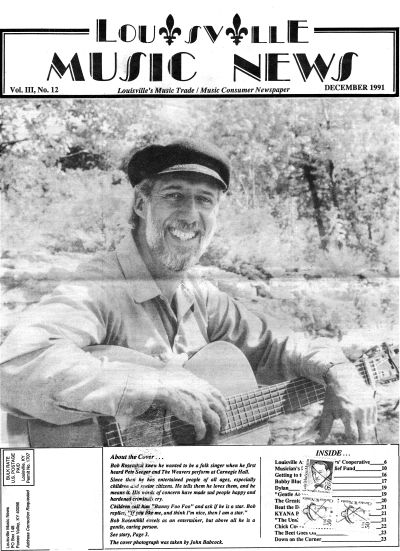

Bob Rosenthal, Folk Singer

By Jean Metcalfe

After interviewing Bob Rosenthal for this article I concluded that no matter how many words I typed I would not be able to convey to our readers what Bob Rosenthal is really like. There is so much to tell, so much about Bob that words can't describe, that I wish everyone could have the privilege of spending several hours with him as I was fortunate to do one warm, sunny day in mid-November.

"Do you like what you're doing?"

"Why'd you start?"

"How come you're a folk singer?"

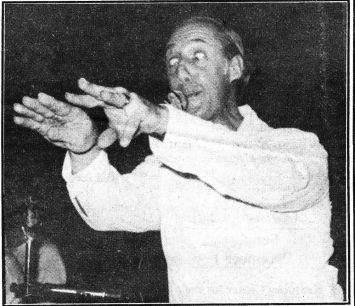

Bob Rosenthal is frequently asked these questions by the children at his performances. And the kind, caring folk singer always gives them an honest answer. He not only entertains them, he makes them feel special.

"You're already wonderful," he says. "The only problem is that you don't know it yet."

He tells them he loves them and he means it.

He does the same for senior citizens and for inmates at a correctional facility.

He can deliver a sermon without preaching.

I do not know anyone who has better rapport with his audiences than does Bob Rosenthal.

Today, at age 50, Bob seems content and happy. Perhaps it is because he now knows that he is a wonderful person. But a good bit of the credit must also go to the special lady in his life, Nanine Henderson.

Bob has not always been at peace with himself. While trying to convince others that they were special, he was unable to convince himself that he was special.

He has known the pain of poor self-esteem, and the consequences of excessive drinking and gambling. He longed to hear his parents say they loved him.

Growing up in Passaic, New Jersey, where he was born in 1941, Bob was a habitual stutterer. The condition continued through his elementary school years.

"I couldn't even say my name in school -- really stuttered profusely."

And the more Bob would stutter, the harder his parents would try to help him. But calling it to his attention only increased the sturrering.

"They did love me. They didn't know how to stop this stuttering."

The other kids would laugh and make fun of him.

"And I really had a hard time thoughout elementary school. And I overheard a teacher tell my mother that I was dumb. And my I.Q. test said I was an idiot, and they said it in front of me, and it stuck with me all my life, until the age of almost 38 years old."

The change came about after Bob moved to Louisville and received counseling from an "incredible" gentleman, David Cull, a former pastor at Central Presbyterian Church.

Although "a real rebel" in high school, at age 16 Bob was put in charge of a game room, because he worked well with children. Even the older kids respected him, he said, and followed his directions.

"I wasn't a big person, but I guess I was a nice person .. although I didn't know it," Bob said.

"I loved kids. I did tumbling, I did body building, which I still do."

In 1958, the year he graduated from high school, Bob was dating a young lady who lived across the Passaic River in Rutherford, N.J. On one occasion she invited Bob to accompany her and her parents to a Weavers concert. Bob accepted the invitation, then asked, "The Weavers, who are they?"

Bob's first encounter with folk music was from a third-row seat in Carnegie Hall, with Pete Seeger and The Weavers on the stage.

Bob enthusiastically described that evening:

"They're doing (Bob starts to sing) 'Tzena, Tzena, Tzena, Tzena, da da la da ...' and then 'Irene Goodnight' and then 'On Top of Old Smoky,' and I'm saying, 'On Top of Old Smoky?' And then, of course, 'Michael' was a big one then .. and then Pete Seeger started doing 'Wimoweh' and then he started doing 'The Drinking Gourd' and I'm saying, 'Oh, God.'

His friend's parents told him he would have to sit down so the people behind them could see.

"Well, it never left me, this group, the sounds, the way they related to the audience, it never left me," Bob said.

He soon broke up with the young lady, but the concert had made a lasting impression on him.

And Bob had made a lasting impression on the young lady as well, literally. Once during their friendship he had tried to kiss her, she had dodged, and his chin hit her forehead. It took two stitches to close the wound, Bob said.

Up until the time of the Weavers concert Bob had had no interest in performing, although he had always loved traditional country music.

Shortly after the concert, Bob bought "a very, very cheap guitar, a Stella guitar, for $13, 'cause I knew I wanted to be a folk singer."

It wasn't long before the Stella was replaced by his present beloved Martin guitar.

While the Martin guitar was still quite new, it played a prominent part in Bob's engagement to a young lady.

"I sang to her, with this guitar, 'The Riddle Song,' with different words," he said.

Bob sang for me his version of "The Riddle Song," and then picked up the story where he had left off:

"And after I sang it to her .. I was shaking, and I gave her the ring, and then I took the capo off .. and dropped it right there," Bob said, pointing to a spot on his then-new Martin guitar.

Bob told me that after he was "dumped" by his fiancee, he was "crushed." He subsequently concluded that he needed psychiatric help: "I knew something was wrong."

His grandfather, a builder, gave Bob's mother $900 "to get Robert okay."

They selected an excellent psychiatrist whose fee was $50 per session, a great deal of money at that time. On his first visit to the psychiatrist, Bob was given a couple of tests. The following week, during his second visit, the doctor asked Bob what he wanted to do with his life.

"I didn't even stutter," Bob related. "I said, 'I want to be a folk singer.'

"He says, 'Really? What's that?'

"I said, 'What? You don't know what a folk singer is?'"

"When he said, 'What's that?,' I said, 'Doctor, if you don't know what a folk singer is, then I believe truly you need more help than I do.'

"I got up, Jean, I walked behind his desk, I opened it, took out the $50 check that my mother wrote, put it in my pocket .. I wasn't in the office for more than five minutes, and I walked out smiling and really happy."

Bob ended the story in punch-line fashion:

"He called my mother up .. and he says, 'Mrs. Rosenthal, your son's gonna be just fine, but you do owe me $50.'"

We both laughed.

"I knew by the Weavers, Jean, that I had to relate to people," Bob said

"I used those folk songs because the folk songs were the songs of the people. They were one-on-one, they were experiences, and they were exciting. Really exciting."

With rapid-fire enthusiasm, Bob told me about a phone call that he had just recently received from Charlie Greenspan. He said that Greenspan is a gentleman who had years ago allowed the young "Rosie" to practice in his store window for about 8-10 weeks straight, building up a repertoire of folk songs. Bob recalled some of the songs he would play: "Hush Little Baby," "Tom Dooley," "Study War No More," and his theme song, the Weavers' "Lonesome Traveler."

"Hush Little Baby" is the first song that Bob ever learned to play on guitar. He paid $5 for the lesson.

It was while playing in Greenspan's shop window that a customer heard Bob and hired him for his first job, at a "fiesta" at the local YWCA. He received $15 for the performance.

He later went on to play at The Twilight Zone Coffee House in Teaneck, N.J., making "30 bucks a night."

During his engagement at the coffee house, Phil Ochs came in and asked if he could do a guest spot with Bob.

"I said, 'Yes sir.'"

Months later Buffy Sainte-Marie came in.

"Can I sing on your stage?," she asked.

"Oh, sure, Buffy," Bob replied.

"She was great and I loved her husky voice," Bob told me.

Later, after Bob had returned from a stint in the Army, he went to Greenwich Village to see Buffy Sainte-Marie.

Hoping for a chance at resuming his career as a folk singer, he asked Sainte-Marie if she remembered him giving her a spot on his stage at the coffee house in Teaneck. She said she didn't remember him. The disappointment was apparent in Bob's voice as he related the incident that happened so many years ago.

"But that's the way it goes," Bob brightened, admitting, "I was hurt." Then he dismissed the incident.

Meanwhile, back in Teaneck, Peter, Paul and Mary came to the coffee house to audition for the owner, Gordon Speevack.

Bob said that Speevack told them that he couldn't use them. He didn't feel that they weren't good enough.

"And they went straight from there to the hungry i," Bob said. "The rest is history, okay?"

Bob said that he had told Speevack that "they really aren't bad. They're really pretty good. They're all together and smooth."

Then Bob related how he really felt about their performance: "They were just incredible, and this tall woman and two little guys .. and they said [to Speevack], 'Oh, okay,' and they went right to the hungry i. They appeared in the hungry i, I think a month later, and went right to the top."

From Teaneck, Bob went on to perform at the Ill Cafe in South Orange, N.J. Then he was drafted into the Army.

"Everybody was burning their draft cards in the Village," Bob related. "They were walking and marching and my dad said, 'You gonna do that, too?' And I said, 'No, I don't believe in that.' .. I don't believe in fighting and killing, but I believe in my country."

"I believe in (pause) I believe in (he chuckled a sort of "this-may-be-kinda-corny-but" chuckle) love. I like people being happy. I don't like prejudice of any nature.

"My mother would get so upset because I sang a song against the Klan, the KKK, and I'd go into New York City, and she would say 'They're gonna kill you. They're gonna kill you.' And I would say, 'Then I'll die for something that's right.' I said, 'Prejudice is no good.' .. There's no room for prejudice, there's no room for bigotry. So I really voiced out about that stuff. .."

After being drafted Bob was sent to Ft. Dix, N.J., and later to Ft. Gordon, Ga.

While at Ft. Gordon, Pvt. Rosenthal entered the soloist division of the Third Army folk singing contest. He also teamed up with Ken McDowell, a friend from North Carolina, to compete in the group division as "The Bobsy Twins."

For his solo performance Bob selected "Mr. Bilbo" and "John Henry." His captain had earlier disapproved of "Mr. Bilbo" -- the committee referred to it as the song "about the prejudice thing" -- but approved of "John Henry." Bob declared he would not enter the contest unless he could perform "Mr. Bilbo." Bob won out, but was assigned the unpopular opening spot, before a crowd of some 3,000 people.

He was followed by other acts that he described as "awesome" and "fantastic." Bob thought he "didn't have a shot."

"I was praying for third," Bob said.

But when the third-place winner was announced and it wasn't Bob, he told McDowell that if he couldn't win at least third place he didn't want to stick around. McDowell chided Bob for being a poor sport.

Just as Bob was departing he heard the announcement: "First Place, Bob Rosenthal."

"And I absolutely froze. I walked all the way back, the general kissed me, gave me a gold wristwatch. I had taken first place," Bob said.

In the group category, "The Bobsy Twins" performed "All My Trials," "Tom Dooley" and other folk selections. And although it was said that their performance merited first place, they were officially awarded second place. Each of the "Twins" received a second-prize radio.

Bob said that MPs were badly needed in Vietnam, but he was one of only five from Ft. Gordon who were sent to Germany.

"By the way, most of my friends went to Vietnam," Bob said quietly, "and a lot of them didn't come back."

"That's why it ticked me off when Joan Baez was protesting everything .. because I was really pro-American. .. I know we all make mistakes, but, my God, these were our boys, our women .. they're ours .."

While in Germany with the Army, MP Bob hatched a plan:

"I was singing all over. I was singing for the enlisted men free. So I figured since I'm going AWOL, I'll volunteer for garbage detail in the early morning, do garbage detail, then put my MP suit on, and then go out and sing at night. I was a garbage man for about three months. They called me 'Pelican Nose.' .. I can't imagine why they would call me Pelican Nose, he laughed, then explained:

It was with endearment."

"Now, one thing you don't do in the Army is volunteer," Bob told me, "but I had a reason for volunteering, because I was getting away with murder at night, or so I thought.

"Six months later, we're all in ranks in Stuttgart, Germany. .."

A wonderful story teller, Bob related how he was summoned before the captain (the guys had all covered up for him, he said) and "boy was I scared."

In an emotional aside, Bob related an incident involving three guys from his room who were outspoken in their hatred for a particular minority group. They referred to Bob as "the n----- lover," although Bob told me that he knew that they really liked him.

Before a concert that he was to give in the recreation hall, the three roommates told him, "Well, man, you know, go do your s---, Bob, we ain't coming to hear you sing that s--- that you sing all the time.

"Knock 'em dead, man, we ain't gonna stand for that s---," Bob imitated their words.

"I said, 'Okay, fellows, you're up front, you don't talk behind my back.'" ("I'm getting choked right now," Bob said, validating what was apparent)

"Jean, when they opened the curtains up, the three guys were in the front row (Bob could hardly continue as he fought back the tears) .. of my concert, and they were the first three to stand up for a standing ovation."

Meanwhile, back to reporting to the captain:

"I was shaking, because I knew I had been a 'bad boy.'"

"Well, Rosenthal," said the captain, "how do you want your coffee?"

"I said, 'Black,'" Bob went on.

"You got it! Are you all packed?"

"Packed for what, sir?" Bob asked.

Said the captain, "We know what you've been doing all these months, volunteering for garbage detail, being an excellent MP, not writing up a sergeant [for a specified offense] because he was going to retire pretty soon .. because he would be bounced out of the Army on his private pay, and he had been in for twenty years. We heard all about that. You're one he-- of a nice .. You're going to Augsburg, Germany, to entertain the troops all over Europe."

"Oh, God," Bob continued, "I just about freaked."

"Well, to end my story of those three guys in my room. Here again, it gets me .. it's like I can see it yesterday. .. They were arguing among themselves who was going to carry down my duffel bag and who was going to carry my guitar, and they all hugged me, and they said, 'You know, we're just what we are, but we like what you are.'"

Bob was reminded of another incident during those days before he departed on his European tour:

"We failed an inspection once, and our sergeant was a black guy, and I said, 'That g-- d--- ..' -- again that word -- and I didn't mean it, but I wanted to say it because they were going to get docked .. they all had girl friends, I didn't have a girl friend, I didn't care if I was docked or not that weekend. We couldn't get passes."

But when Bob used their own expression to describe the black sergeant, the guys said, "Da--it, we can say that sh--, but you can't. It don't sound right coming from your da-- mouth!"

Bob performed all over Europe, singing for the German forces as well as the American forces. He developed a costumed character and sang "John Henry" and "Mister Bilbo."

A priest enlisted Bob to do a character guidance class with him to help boost the guys' morale.

Bob would say to them, "You know, if I cut that black son of a b---- right there, he's gonna bleed, and if I cut that white so of a b---- right next to him, he's gonna bleed, too. And when I cut the first son of a b---- who doesn't bleed, I'm gonna be prejudiced. I'm gonna be scared witless .. You get my point, fellas? We're all human beings, and we gotta care about each other."

The chaplain was very impressed with Bob, and insisted that he go back to the barracks and write a song about what he had said. And Bob insisted that he was not a songwriter. But the chaplain wouldn't take no for an answer. So Bob became a songwriter. He penned "Every Man Bleeds," which he would later include on his first album, Listen My Friends.

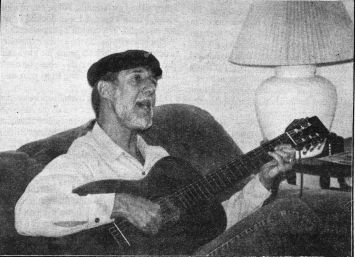

At story's end, Bob agreed to play and sing for me "Every Man Bleeds." Very stirring and thought-provoking. Bob should write more songs.

He has written only one other song, "On My Journey Home," about President John F. Kennedy. When I questioned why he doesn't write more, he replied, "I don't think I have the gift."

I don't think I agree.

Bob went on to say that it was only about five years ago, while working with Mary Ann Maier for "Operation Brightside," that she analyzed "Every Man Bleeds" and convinced him that it makes sense.

Having mentioned the song he wrote about President Kennedy, Bob backtracked to relate that he had been scheduled to do a concert at Kossuth Hall in New York City on November 22, 1963. Despite President Kennedy's assassination earlier that day, Bob did not cancel the evening performance. He chose instead to eliminate the comedy and dedicate the concert to "this great man." He had a full house.

The song "Every Man Bleeds" "went around the world three times," Bob said, "and Radio Free Europe twice. And my parents were investigated by the CIA because they had heard I went to The New School of Social Research, for folk music. When they heard of The New School of Social Research it scared them. Social? Huh? Huh?"

"I had some skepticism about my country. .. We all do. We all have doubts," Bob said. "I have doubts now," he added with a chuckle, "about politics and crap. .. I think basically we have the right idea."

Bob described another incident that occurred while he was in the Army:

"I was in the field. I was a folk singer, VIP treatment, 24 guys in the 22nd Infantry Division Entertainment Group that I belonged to in Augsburg, Germany. A colonel came out to the field and we had our gear on, and he happened to come up to me. We didn't have our names on.

"'Where's Private Rosenthal?,' the captain inquired.

"I said 'Sir, why are you asking?'"

(Bob imitated the colonel. His was a very angry colonel) 'You don't ask a colonel a question like that, son. Where's Private Rosenthal, and don't you ..'

"I said, 'Sir, it's me.'

(Bob as the colonel again, blustering) "'Oh, okay, well, you caught me off guard there with that question.'

"He says 'Congratulations.' Bob continued.

"I said, 'What for, sir?'

(He replied) "'Your song. That song you wrote. I want you to know that your parents and your whole family was investigated by the CIA and your song went to Berlin. "Every Man Bleeds." That your song?'

"I said, 'Yes sir.'

"'Well,' he said 'it's the Army's song now, you know, 'cause you're part of the Army (Bob hesitated, as if he were talking too much, but I encouraged him to keep right on telling it just as he had been doing)

"He says, 'We investigated you and everything else, and your song is gonna go around the world three times and Radio Free Europe twice, and every Army base is gonna hear that song.'

"And I said 'But, sir, it's against war.'

"He says, 'Da--it soldier, we're against war,' and I said, 'Yes, we are.'"

"And I was very proud of my country then."

Bob shifted gears, and raced into another Army story:

"So I'm singing at this big party, all generals ..

"And I'm going to try to do this song for you," Bob said to me.

He sang, a cappella, a portion of the song titled "Little Dead Girl of Hiroshima":

I come and stand at every door,

I knock and yet remain unheard,

For I am seven ..,

When children die they do not grow.

My hair was scorched by swirling

flames,

My eyes grew dim, grew dim and

blind,

Death came and turned my bones to

dust,

And that was scattered by the wind.

I need no tea, I need no rice,

I need no sweets or even bread ..

Unable to remember exactly how the song went, Bob promised to brush up on the words and put the song on a tape for me.

"The point is, the last verse says that why this child died, and why we fight today, is so that children of this world can live and laugh and love. We have to stop tyranny. So this is why we had to fight, so this .. would not happen again.

"Well this general got irate, and he says, 'That song .. stinks ..'

"And I said, 'Sir, you're drunk. If you weren't drunk you would see where I was coming from.'

"When I said that to a general .. the whole room went silent. .. "

"Honey, I was pi--ed," Bob said to me. "He hadn't heard a word I was singing. They were all drinking booze."

Bob was 24 years old at the time.

Bob said he sang the song again, and afterwards the general apologized, shook his hand and said, "Great song. You're right. I'm sorry."

"So that was great," Bob said with obvious satisfaction.

Shortly before Bob returned home from the Army, Ed Sullivan was in Passaic to conduct interviews for his popular television show. While there, Sullivan spoke at Bob's mother's Hadassah. Mrs. Rosenthal told him about her son, the folk singer, and asked Sullivan if he would give Bob a listen. The famous television host told her to have Bob come to New York City to perform for some of Sullivan's staff.

Fresh out of the Army, Bob and McDowell went to New York for an audition.

"Our notes just hit like crazy," Bob said of their performance.

(Digressing for a moment, Bob said that the same is true for himself and local folk singer John Gage, and that he hoped they could one day do a concert together)

Of the audition, Bob said that they were told by Sullivan's representatives:

"You guys are great, you are great, and if you were women we'd have you on the show. We need women right now."

Kenny McDowell was sick, Bob said, and he got back in his car, not even spending the night, and drove straight back to Ashville. Bob never heard from him again.

"What hurt me was that we had served our country for two years. That's what kinda bugged me, and they said 'Rush 'em up here.'"

They had arrived to audition at 1:00, Bob said, and were out "by almost 1:05."

"We sang 'All My Trials,' 'Five Hundred Miles' and 'Hava Nigila,' and we did a he--uva job. It was wild."

While stationed in Germany, Bob had met a woman from Anchorage, Ky. Their friendship, plus Bob's desire to be independent, later brought about Bob's move to the Louisville area. His first job was at The Chick Inn at Harrods Creek.

The relationship with the Anchorage lady didn't work out, but Bob stayed on in Kentucky.

A couple of years later he met and married his first wife, Mary Jane, whom he described as "a very devoted, wonderful wife, but probably an enabler.

"She took all of my crap .. that she shouldn't have taken as a person. And I feel bad about that, but I've had to grow. And I drank a lot. And the children were born and I was a drunk. I was a drunk. All based on low self-esteem."

Despite counseling, the marriage eventually broke up.

A regular performer in night clubs for some 27-28 years, Bob said there once was a period of time when he "dreaded going to work Monday through Thursday. And my salvation many nights .. between 1970 and 1975, I was virtually drunk. I would consume almost a fifth of scotch every two days because it was free, it was there. .. Many entertainers, I think, or people in general, use a substance to motivate them, to give them the nerve to get on the stage.

"I've always been a ham. I always wanted to scream for attention. .. We all do it in a certain way. It can be a car. It can be a house. It can be jewelry ..

"So, I was singing, and I dreaded going to work many nights because it was slow and I needed a friendly face -- I use Leo Buscaglia's term "happy eyeballs" -- to sing to. .. I like eye contact.

"So there were nights I dreaded it. But I knew what was coming on Friday and Saturday, and that's what kept me in the business all these years. .. The fact that I would have a packed house of friendly faces. .. Come Friday and Saturday I was in heaven."

"In 1975 -- I had been drinking from '70 till '75 -- I decided to go into the school system and do shows on self-esteem, because, like in the book 'Illusions,' you teach best what you most need to learn."

The shows are called "I Like Being Me."

"Three priests in my life," Bob said. "One when I was eleven years old. Isn't that funny? Jewish guy, and blessed by the Catholic church so much."

Priest No. 1: At age eleven when Bob had a fever of 104 degrees that wouldn't break, and efforts by a Jewish doctor and a rabbi didn't seem to help, Mrs. Rosenthal suggested to her haberdasher husband that he call "this priest friend of yours," referring to the priest at the Catholic church behind Mr. Rosenthal's shop.

"My father was a very charitable person," Bob said, "and he always gave a set of clothing to all the choir boys in the church, and the priest."

The priest came to the Rosenthal home and knelt and prayed for Bob, then sat down to drink the tea that Mrs. Rosenthal had offered.

"By the time they were having their tea, I got up and started roller skating in the apartment. I was all better."

The second priest of the three that Bob referred to was the chaplain in Germany who had prompted him to write "Every Man Bleeds."

The third priest, "the greatest priest of all," was Father Joseph McGee, who was killed in an automobile accident several years ago.

"The man always gave me a $20 bill on my bar stool at Village Inn Pizza Parlor. He loved me, he loved what I stood for, he liked 'Mr. Bilbo,' he endorsed me for all the Catholic schools."

Bob said that he told Father McGee to give the money to the church and to pray for him. But Father McGee persisted, saying he knew that Bob had two children to buy shoes for, and that he would still pray for him.

"He taught me something too .. I spread these words wherever I go. Maybe I'm an entertainer, maybe I'm a lecturer, I don't know. But certain things hit me. Like Si Kahn's latest song is my theme song for the rest of my life. I do it in all the schools. .. I wrote a letter to Si Kahn saying I think it is the greatest song ever written -- 'What You Do With What You've Got.'"

Bob sang it for me, at my request, and it is difficult to say who enjoyed it the most -- performer or audience.

Once when Bob was asking Father McGee a lot of whys -- why do people have to kill, and why do they have to die, and why do they have to suffer, and others -- Father McGee told him:

"That which comes from your mouth is your personality, and that which you suffer from within builds character."

Bob shares those words with his audiences at nursing homes and senior citizens' groups, adding:

"And many days we wake up and say, 'God, just today, no character building. Give me a rest.'"

I laughed and Bob said, "Thank you for laughing. Everybody gives me the same reaction you just gave me."

On the subject of words of wisdom, Bob told me that he follows the advice of his grandfather, who told him to always say thanks when someone says or does something nice for you, and to always help someone else while you are getting more popular.

Two of Bob's favorite sayings are "None of us are getting out of this world alive, and "We're all trying to get to the same place."

Bob then sang for me the Si Kahn song "What You Do With What You've Got."

"That's my life," Bob said when he had finished.

I said to Bob, "I'll bet you don't have a concert, even if they don't tell you so, that you don't touch someone."

"They do tell me. And I'll tell you something .. it freaks me out. I'm not trying to be humble, it's not one of my attributes, and yet I guess I am, because I thank God."

Bob recalled a hurtful incident once in which someone said to him, "Well, you're just an egotistical maniac."

"I said, 'Oh, no. Every time I touch somebody, I thank God for that. I know it comes from God, not from me. I'm just a human being like you are.'"

Bob continued, "I believe in God, and I'm not trying to use God's name in vain. I say the Twenty-third Psalm every single night. It's a habit of mine, since I was 13 years old, and I was Bar Mitzvahed. I don't believe in that, but I do believe in the Twenty-third Psalm. I believe in God, I believe in Jesus, I believe in whatever you want to call God, a higher spirit .. I don't get into the politics of that.

"But, yeah, I have people tell me that [that his performance has touched them] all the time. And I say, 'Thank you .. maybe I'm saying that to you because I'm saying it to myself.'

"Here again, you teach best what you most need to learn. So I'm still a scared little boy."

"My mother said to me years ago -- she's stopped saying it now -- .. 'You talk too much.'"

"Jean, let me tell you why I'm talking so much. .. I'm talking so much because I want to help somebody else's life. I hope somebody, anybody, one person reads your story and it makes that person think twice about doing something stupid."

Bob related how he uses his trademark song "Bunny Foo Foo" -- his daughter Lisa taught it to him years ago -- to teach that people who take drugs are, in the words of the song, "hare today, goon tomorrow." He also tells them that we must clean up our Earth and recycle, that garbage is to be "hare today and goon tomorrow.

Bob spoke of visits to the Luther Luckett Correctional Complex and showed me a plaque that the inmates had given to him in December of 1988, making him the first honorary member of their fine arts club.

He said that after a performance there a young man had come up to him and asked if he was an ex-con, because of the way he had related to the inmates.

Bob explained to the young man: "Sir, I'll tell you why I can relate to you all, the way you think I can -- and that's a compliment, what you're telling me -- because we're all serving time. You happen to be here, behind bars. I'm serving time out there. My father served time, my mother served time, all human beings serve time. We serve it in different ways. We all pay our dues. We all have depression. We all get down. .. We all want to scream sometimes. You took a different avenue. I don't know what you did. I don't want to know what you did. But you know that according to society's rules it was wrong, so now you're serving time where you can actually see that time you're serving. I don't always see it, but I feel it."

Another inmate, a very large man in his forties, asked Bob if he could hug him. Bob consented. As they hugged, the inmate whispered that he was serving 102 years without parole.

"Wow, it must've been a doozy," Bob said to him.

"Yeah," the inmate replied, "I'm a sick person. I'm a bad man. .. You were so good today, you got me through Christmas. .. I wish somebody would've told me they loved me, like you did tonight, when I was young. I wouldn't have done what I did," and he started to cry.

The man's mother, who was there for the performance, asked her son why he was crying. The man told her that it was because Bob had told him that he loved him.

"I've never seen him cry," the mother said to Bob.

Bob choked back the emotion as he said to me, "This is the first time he's cried. He's forty-something years old. .. He's gonna die in prison. And these kind of things touch me."

As we looked at the plaque, Bob told me that the administration personnel had said to him at the time, "We don't know what the he-- you did to these guys, but no one's ever gotten this in all the years we've ever been here."

Perhaps it's because Bob cared enough to perform for the guys for free the second time when they wanted him to come back but had no money in their club fund. Bob does not earn a lot of money from the performances he does, so it's not as if he couldn't have used the money.

"I don't worry about it," Bob said, "I don't worry about it. .. It comes back to you. It does. It really comes back to you."

To emphasize his point, Bob sang for me a Willie Nelson song, which he said was one of the first songs the famous songwriter-performer ever wrote.

I told Bob that I, like him, was a Willie Nelson fan.

"Wait'll you hear this song," Bob said, "because you've never heard it before."

Hah! Bob underestimated this Willie fan!

But that only doubled the pleasure of hearing Bob sing "In God's Eyes." These are a few of the words:

Lend a hand if you can to a stranger,

Never worry if he can't repay,

For in time you'll be repaid

ten times over,

In God's eyes he sees it this way.

"That was Sarah. She was a giver and giver and giver," Bob said of Sarah Adams, who recently died of cancer. Her husband, Ed Adams, a musician and educator, was active in Louisville Homefront Performances before accepting a position in Indianapolis.

"I guess people should just care about other people more," Bob said.

He told of an incident that happened one night as he and Nan walked on Fourth Avenue after attending a performance by his friend Dean Bolton at the Brown Hotel. It involved a generous gesture on Bob's part, which caused the recipient of Bob's generosity to say, "God bless you."

"Mister, God bless you, too," Bob said to the man, "We all need each other."

"And that's what I care about," Bob told me.

"Nan's very proud of me for being a folk singer. I'm very proud of her because she really cares about her patients. (Nanine Henderson is a doctor) She's a very, very good person," Bob said.

"For years I sang for the applause. I needed the applause. Applause is for two things, needing it and enjoying it, appreciating it. I don't need it anymore. I do appreciate it."

I asked Bob where his musical talent came from.

"Where it came from I'll never know. It was never in my family. My father was a haberdasher. I heard years ago he played violin. I still remember one of the first songs I ever learned," Bob said enthusiastically as he began to sing:

"I sell the morning paper, sir, my name is Jimmy Brown, and everybody knows that I'm the news boy of the town. You can hear me yelling 'Morning Star,' running along the street, I got no hat upon my head, no shoes upon my feet.'

"Little Jimmy Dickens," Bob explained.

The entire room seemed to be filled with enthusiasm, and Bob said:

"Boy, you brought out the best in me today." He immediately remembered another incident, and plunged into its telling :

He once sang his extensive repertoire of union songs in a Southeast Coal Company mine, in Letcher County.

"You know, son," a coal miner said to him after the performance, "Kentucky has 120 counties .. and you're a fine folk singer. Only one county in Kentucky is non-union, and your union songs are great, but you just sang them in that one county."

While there Bob jammed with Marion Summer, who plays the fiddle in "Coal Miner's Daughter," and who also played with Roy Acuff, Bob said.

"I met all these good people down there. Here I was, [with] a ponytail, a name like Rosenthal, and people still loved me. .. People love smiles. In Eastern Kentucky you don't fool people. If you do, you're gone. .. But if you're honest, up-front and good .. they liked me down there. I was there for five days and it was just awesome, awesome.

"All my shows down there I sang for free. I wanted to give back to Eastern Kentucky what they gave me. They gave me a living all these years, by singing their songs -- 'Barbara Allen,' 'The Riddle Song,' 'Greensleeves,' 'On Top of Old Smoky,' 'Old Fool, Blind Fool,' 'Harlan County Boys,' 'Sixteen Tons,' 'Dark As a Dungeon,' 'Nine Pound Hammer' -- these all came from Eastern Kentucky. So I wanted to just pay back, and I did, and I felt good about that."

Driving up Pine Mountain during his visit to Eastern Kentucky, Bob heard Judy Collins singing "Amazing Grace."

In the midst of a failing marriage, with Judy Collins singing "Amazing Grace," Bob started to cry.

"And I said, 'Please, God, forgive me. I have been wrong. .. Give me another chance.' And she was singing this song and I was just bawling in my car."

Bob has been singing "Amazing Grace" ever since that experience.

Bob regularly performs at area nursing homes. During one such performance, a lady walked in and Bob could see that she was miserable.

"I mean, she's so sad," Bob told me, "and I kinda pride myself on making people smile and sing along with me. It's an ego trip, it's a power trip, I love it. I don't just love it that they're doing it, but I love it that they're doing it for me too. It's a two-way street.

"So, she doesn't react at all. I'm trying to be funny and silly and she's not .. Well, halfway through my show I begin to do 'Amazing Grace.' And she starts singing it with me. And she lights up. After the song, she continues to stay lit up, right in front of me."

She beckoned Bob to come to where she was and asked if he could talk to her.

"I sure can, especially to you," Bob replied.

"Why especially to me?," she wondered.

"Because when you walked in here," Bob explained, "you were so sad."

She related to him the reason for her sadness:

"My children brought me here two months ago. I haven't seen them since. They took my house away from me. They sold my car. I'm only 79 years old. My mind is fine. And I don't have anybody in the world. Thank you for noticing me when you sang 'Amazing Grace.' I don't know why God still has me here."

Said Bob: "I beg your pardon. You don't know why God still has you here. I do. And I'm not that smart."

"Why?," she asked.

"Don't you know what you just said to me? You thanked me for noticing you. That's why God still has you here, because I need that. I need to be noticed. You noticed me to call me over to you. I noticed you were sad."

"The end of the story is this: It isn't ended yet. She's still doing fine. She has more friends there now than anybody there. Everybody loves her to death."

A couple of months later Bob returned to Passaic to visit his mother, and while there he told her the story.

"And I never sing around my mother," Bob told me, other than a couple of shows some thirty years before.

Bob sang "Amazing Grace" for his mother, at her request.

"Robert, I'm so proud of you. I've never heard you sing a more beautiful song in my whole life."

Bob started to cry and his mother asked him why.

Before Bob finished telling the story, he explained his tears to me:

"The reason I cry now is because when I was young I was told not to cry. Part of my show is 'It's okay to have feelings, it's okay to laugh and it's okay to cry,' and I use 'Old Blue' (a song about a dog who dies) for that .."

Bob picked up the story, telling how he replied when his mother asked why he was crying:

"Mom, I've waited all my life for you to tell me you were proud of me, and this song made you tell me."

In an affectionate high-pitched imitation of his Jewish mother's voice, Bob repeated her words:

"Ohh! This song is wonderful! It's beautiful!"

Bob's reply to her:

"Mom, do you know it's a Christian song, and you're telling me it's beautiful."

Mrs. Rosenthal: "Ohh! What are you talkin' about? That song's for everybody! Amazing grace is God. Who doesn't matter which god. It's God! It's amazing! You keep singing that song, Robert, and you'll be fine. That's beautiful."

Bob concluded, "And I tell that story wherever I go. I tell it in the Jewish temples. I tell it in the Catholic, Baptist, Presby .. you follow me? And I say, 'You know what, folks? If it's good enough for my mother, it's good enough for you.'"

Bob and I told each other about our respective parents, and we shared laughs and tears alike. We both like to talk, but we also know how to listen.

"I call my mom every single day to tell her I love her, because I couldn't do it earlier in my life, and she couldn't do it to me."

"And they're not very expensive phone calls, to Passaic, New Jersey. We don't have to talk very long, but just enough to say 'I love you. How you doing?,' because I know that she won't always be there. .. I wanta hear her voice every day I can."

I asked Bob about his albums. He told me that he recorded his first album, Listen My Friends, because people were always asking him why he hadn't made one, and declaring that if he were any good he would make an album.

"The point is," he said, "anybody can make an album. All you need is a couple of bucks and you make an album."

But Bob recorded the first album and had 500 copies pressed.

"And I swore I'd never make one again, unless somebody would pay for it .. If I'm so good, then someone else should pick me up and give me a contract. Years went by .. and I started doing children's shows. .. And I listened to my inner self. And people should listen to their inner selves, because your self says good things."

"And I was broke. I've always been broke, Jean. I made money and I spent it at the track, and I've always had no money. But I do thank God that right now I'm okay, I've gotten jobs .. people keep calling me up, and referrals and everything. Things are a little bit slower this year than last year because of the economy, but I'm not complaining, because I really feel God has been very, very good to me. So I never want it interpreted as complaining."

"So 1984 rolled around and I was broke .. I was broke. I called my mother and said, 'Mom, it's time for me to make an album, a cassette. Can you loan me a thousand dollars? It's about twelve hundred or thirteen hundred to make it, but can you loan me a thousand?' She says, 'Sure. Don't worry about it. Sure.'

"I don't like to ask," Bob told me. "You follow me? But I had to ask. I knew it was the time I had to do it. She sends me a check right away. I make the Bunny Foo Foo Loves You! cassette. And it started selling.

"Well, on Bunny Foo Foo alone, I've gone to Florida four times .. to visit my children. I have sold over six thousand. No, I shouldn't say sold. I have distributed over six thousand copies."

"You've given some of them away," I suggested.

"I've given a lot away. I like giving away, because you give away and it comes back, and it's a good feeling. I like giving away."

"They say I've sold more children's cassettes than any other one folk singer in this town. .. And I'm amazed at that. "

In 1986 Bob recorded Nothin' But Beans, a cassette album that contains a very nice selection of songs. Among them are "Long Black Veil, "Black Is the Color, "Danny Boy," "Harlan County Boys" and "Strangest Dream."

A couple of years ago, Bob said, he called up his mother and said that he had some extra money and wanted to pay back the money he had borrowed.

Again, the voice of Mrs. Rosenthal came from Bob, with machine-gun rapidity:

"Oh, Robert, (He gestured with his hand, and laughed and said, "I can see her hand." ) don't be silly. Look, just be healthy. Save it. Save it. Just save. Don't spend it, don't drink, don't gamble, just save it. That's what a mother is for. Don't worry about it. I don't want it back. I'm happy you did so well with it."

Said Bob to me, "She really doesn't even know how much she helped me. When I told her .. I had to cry."

"I said, 'Mom, you don't know what you did for me.'

"She said (he imitated her once again), 'Yeah, yeah, yeah ..' I said, 'No you don't. I was desperate. I needed the money and you gave it to me without any questions and I have become very popular because of this cassette.'

"She said, 'I'm happy for you. I'm happy for you.'"

In 1967, Bob was a member of the cast of "In White America" at Actors Theatre. He played guitar and sang. The work was a documentary based on historical documents, political speeches and incidents, and ran for four weeks.

The Louisville Federation of Musicians Local No. 11-637 named Bob the Musician of the Year in 1988.

Bob told me the story of how the union's Rocky Adcock had called him up and coaxed him into coming to a meeting that he had not planned to attend. He described how they conspired to keep him there after he had completed his part on the phony agenda, mentioning the free food that was available.

Bob said that he was eating peanuts during the remarks that led up to the announcement. When he heard words along the lines of "known throughout by children," Bob realized that the award was to be given to him. He remembers hearing these words: "And they call him Bunny Foo Foo."

Bob said to me, "I thought I would die."

"And then, Jean, (Bob starts to cry as he continues the story) I went up there to get that plaque, and I said .., 'See, Dad, I did it.' I wanted my dad's approval all my life, Jean.

"I said, 'I did it, Dad.'"

"Getting that award, I started to cry. And I said, 'I only wish my dad could see me. Oh, I know you can see me Dad.'

"And I said, 'I thank you all for giving me this honor. I never dreamed that I would ever get an award like this. First of all, I can't read a note of music. .. I'm just an entertainer. .. I can't believe you're giving me this honor. .. Thank you. Thank you.' I just freaked out."

"I'm sure it was a popular choice," I said to Bob as he composed himself.

"They said so," he replied quietly. "I always have doubts about myself."

"You shouldn't," I said.

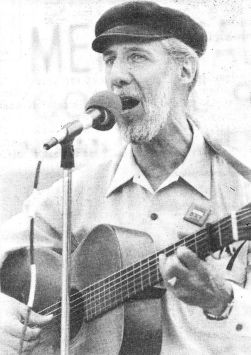

Bob has performed for the local "Operation Brightside" clean-up campaign, and is a regular with the Mayor's "SummerScene" and "WinterScene" projects. He is a natural for this kind of program. Every city should have a Bob Rosenthal.

He routinely runs into children who know him from his performances. They give him the Bunny Foo Foo signal. Sometimes they will walk up to him and go "Uh-oh, uh-oh." Sometimes parents are upset until Bob tells them that it relates to the audience participation part when he sings "Marching to Pretoria," and he admonishes them not to do the "Uh-oh" part. And then, of course, in "Mother, May I?" fashion, he tricks them into saying it.

When children ask Bob if he is popular or if he is a star, he tells them, "If you like me, and think I'm nice, then I am a star."

Bob spoke about Nanine Henderson, his special girlfriend. He said that she is close to his own age, in contrast to previous relationships with women who were 17-19 years younger than Bob.

"And my daughters were offended by that. It hurt my daughters to see their daddy going with a girl only a couple of years older than them."

"And now I meet a woman who's a year and a half older than me. .. We're really wonderful together."

"She is one he--uva woman!," Bob said proudly, "She's a very healthy, lovely woman.."

He proudly showed me her photograph.

"Her sons love me. She's got a twenty-year-old and a thirteen-year-old."

Bob's two daughters, who live in Florida, are Lisa, 22, and Rachel, 20.

Bob and I discussed our dismay at growing older, although we agreed, as the saying goes, that it's better than the alternative.

"I used to be -- this is cray-zee -- I used to be an arm wrestler. And, guess what? I still am. I am in training now. I don't wanta grow up. I-don't-want-to-grow-up.

Nan loves me arm wrestling. She loves what I do, and she comes to a match with me. And I'm training like crazy."

"Now feel," Bob said to me, bending his arm at the elbow and flexing his muscle. I felt. I was impressed!

"I really work out and I want to be a champion. I took third in the country in 1972 in arm wrestling, and The Courier-Journal gave me this write-up (he showed me the article) and I've had more write-ups as a loser than most winners have as winners, because of being an entertainer."

Referring once again to Nan, Bob said: "I met my match."

Bob and Nan plan to travel to Passaic to visit with his mother and his Aunt Rose during Thanksgiving weekend. Then they will attend a gathering of Nan's family.

Bob promised he'd have some very special news for us when they return to Louisville. He was very happy, and could scarcely keep the secret.

"So, after Thanksgiving," he teased, his eyes sparkling devilishly, "you can give me a call and .."

Last year on Earth Day at the Zoo, Bob placed third for his environmental skit. This year he came in first.

"And the biggest award of all, you can't touch," Bob said.

"The biggest award is the one I get from a little child at the Home of the Innocents. I go there once a month to sing. And when you see a child look at you and they want to give you a hug and you know you've touched that person's life.. ."

"I believe this: .. If you touch one person, if you make a difference in one person's life, you have helped change the entire universe. So if I make one person laugh -- and I've done more than just one person -- I know that there's some place for me. And that's the way I feel. And if every person just does one thing for another human being, they've helped change the course of the universe."

I had a lovely visit with Bob Rosenthal. I stayed much too long, but I was made to feel very welcome.

I told Bob that I have a great deal of difficulty keeping my cover stories as brief as I should keep them, and that I was working on the problem.

"As far as your writing the story," Bob said, "I don't care how short it is. I don't care how long it is. I just wanted you to come here and be proud of me."

l

Bob's first album, Listen My Friends, is no longer available. Both Bunny Foo Foo Loves You! and Nothin' But Beans are available through Hawley-Cooke Booksellers or from Bob himself. Additional information can be had by writing Bob Rosenthal, Folksinger, 2161 Goldsmith Lane #6, Louisville, KY 40218, or by calling (502) 458-2720.

-30-