social bookmarking tools:

|

|

| Available RSS Feeds |

|---|

- Top Picks - Top Picks |

- Today's Music - Today's Music |

- Editor's Blog - Editor's Blog

|

- Articles - Articles

|

Add Louisville Music News' RSS Feed to Your Yahoo!

|

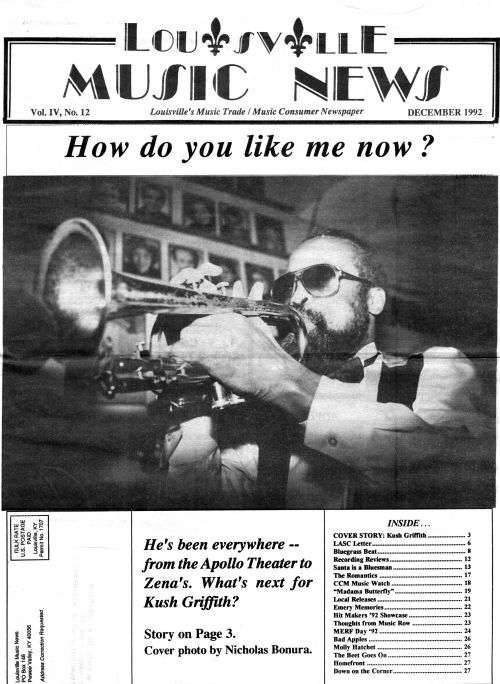

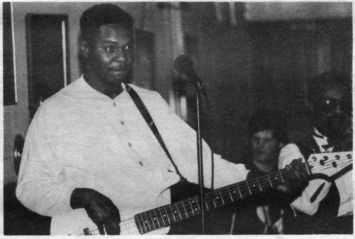

Kush Griffith

Story by Bob Bahr. Photos by Nicolas Bonura

An equipment salesman is in town on business. The travel and the work day hasn't wrung out all his energy and it's 11 p.m. on a Friday. On a Louisville native's recommendation ("If you want to hear good blues, go to Zena's.") he walks a couple blocks from the Hyatt Regency to 3rd and Market and steps inside the small club.

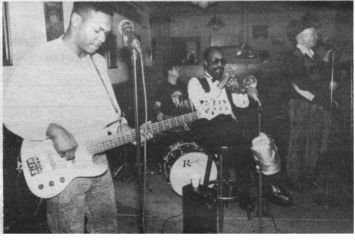

On the dance floor are beautiful women wriggling with well-dressed men, on the walls are framed 8 by 10 glossies of admiring actors and actresses, in the air is blues music. And in one of the comers of Zena's Cafe is Kush and the Sunstroke Blues Band, making the music; a motley group of musicians summoning the spirit of blues, R&B and rock 'n' roll and holding it fast for the entire evening. It's feel over technique, essence over chops, groove over pyrotechnics.

Drummer John Quiggins laying it down solid on a little, 30-year-old set. Bassist Paul Bennett keeping it funky, or walking a line with Ray Brown soul. On guitar is a Louisville legend, Smoketown Red. An albino African American playing with sureness and taste, Smoketown has his cadre of admirers 40 years his junior hangin' out in front of him, schooling on every fill and flourish.

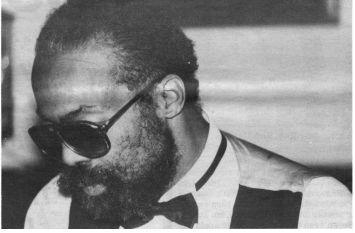

The focus of attention is sitting down on a stool front and center of the band. Dark glasses and a beard lightly peppered with grey hide a face once familiar to all following funk music closely. "How do you like me now?!" Richard "Kush" Griffith III shouts for the hundredth time into the orange, soft-foamed tip of the microphone. He'll shout it a hundred more times before the night's over. He has yet to delve into a rowdy version of "Red House." He still has to preach to the faithful on the dangers of "Mustang Sally." He still has to 'splain that "I'm Tired." How "Everyday I Have the Blues."

Free-form vocalizations sprinkle the jams. Kush picks up his comet, the little brother of the trumpet and testifies with his axe. Our visiting salesman asks himself, "Am I witnessing a show by one of music's biggest talents, or am I catching the once-in-a-lifetime zenith of a cookin' small town band?" The answer is yes.

Kush Griffith lent his voice and talents to the birth of modern funk music, playing an integral role in the bands of James Brown and George Clinton. These two giants formed the final word in funk and soul music. All present and future efforts in these two genres will immediately and unconsciously be compared to the work of Brown and his bands and to the work of George Clinton and his equally adept Parliament-Funkadelic Thang. Kush learned (and taught) with the best and now he is leading a Louisville band on a new path to fame. Over the course of three extended interviews, Kush spoke out about his years with Brown and Clinton and his equally interesting years with other bands. Only a portion can be reported here.

Griffith got the nickname Kush at an early age from his mother.

"I think I was 13 and she sent me shopping at Rose's Department Store for some sneakers that were on sale," Griffith related. "I didn't even try them on and I brought them back and they were a little bit too big. And my mom was like, 'Well, you can trade them in.' And I said, 'Oh no, these are okay. I'll just wear them.' And she was like, 'But they're too BIG.' They weren't that much too big. They were kind of slidin' back and forth, you know. I said, 'That's okay, I'll grow into them.'

"She kept trying to get me to take them back and I was like, 'No, mom, they're okay.' And finally she said something like, 'All right, then keep them, you kush-foot son of a b–h!' My best buddy was in my house at the time, so that next Monday at school it was, 'Kushfoot! Kushfoot!' So it was Kushfoot for a long time, for the rest of the year. And then after a while it was shortened to Kush."

Griffith had already been playing trumpet for four years. His interest in the brass instrument started when he saw someone playing it in an Armistice Day parade downtown. "I saw the trumpet and I said, 'That's it. That's what a guy ought to do. Play that."'

He practiced every night throughout grade school and high school and earned a sterling reputation on the instrument. Scholarship offers came from several colleges, but Griffith chose to attend Southern Illinois University in Carbondale and pay the full price.

While not a model student, Griffith impressed his teachers with his intellect and wowed everyone with his musical talent. When money ran out after one year, he returned home to Louisville's Southwick area and started playing with a band called the Notorious Outsiders featuring a guitar player named Smoketown Red. He was 19.

In I968, his father Richard Jr. was working as a bartender at a place called Club Louisvillia. When trombonist Fred Wesley and drummer Clyde Stubblefield of James Brown 's band came in looking for a trumpet player, the elder Griffith suggested his son. The next day Kush auditioned for the band, playing "Kansas City" and "This Is A Man's World" with trumpeter Waymond Reed and Wesley.

"That was all," Griffith said. "They could get an idea of what range I had, my ability to read and then they asked, 'Can you dance?' 'Yeah, uh, I can dance.' 'What's your draft status?' At that time I still had my student deferment.

"That was the end of the audition. And they said, 'We'll give you a call.' And I thought that was the old 'Don't call us, we'll call you.' "'Unless you can leave right now.' I said, 'No, uh, I've got to give the band that I'm playing in two weeks' notice.' So they said, 'Cool. We'll give you a call.' So it was about a week or ten days later when Waymond called me. And it was interesting the way he said it: 'Hey, you got a gig if you want it.' I couldn't understand that, the way he put it at that time, until later on I understood where he was coming from. Because then, I was thinking it was the greatest thing in the world to play with James Brown. He was the hottest soul act on the road at that time."

"l remember asking these stupid, naive questions, like 'What's it like working for James Brown?' And they'd answer [Kush says quietly and tiredly] 'It's a gig, man. It's a gig.' I didn't know what that meant until later, when I had other naive people, musicians, asking me the same question. Then it was me saying, 'It's a gig, man. It's a gig,'" Griffith said.

So at age 19, Griffith was playing with the self -professed "Soul Brother Number One." The musicianship in James Brown's band was very high, as demonstrated in the band's Brown-less opening set on the traveling revue. Lightning-fast jazz runs raced by, then military-tight horn hits would rattle the rafters. On record, the music was controlled chaos, loose enough for the groove, tight enough to give it enduring brightness. The key, Griffith explained, was in the groove on the first beat of each measure. James Brown called it being "hot on the one."

"That's part of having that heavy bass, heavy foot," Griffith elaborated. "That's where you're going to find the most emphasis is on that one. James put a lot of the horn licks on the one. Very seldom do they go contrary to the pulse — that's what the one is, is that pulse. I guess you could say that that pulse corresponds to a heartbeat that would grip a person — a listener— in a way that was almost metabolic. It was so subtle, they wouldn't even realize it. It was that pulse that James adhered to. The only thing that was contrary to that pulse was maybe his vocals. He could go off on a tangent and stray away from the pulse because his band, his rhythm section, had the pulse, had a lock on it. And it was the center or foundation — the focal point."

Griffith was touring with "The King of the One Night Stands," the top R&B/soul act in the nation. It had its perks.

"Women were important," Griffith began. "If you're pretty much your normal, red-blooded American male, you like women and you like them to like you. But because of what I call that Fat Boy Complex I wasn't real outgoing. But I realized that you could get a lot of groupies to like you just because you were in the band. I found out the true meaning of the word groupies. I had far less than most road musicians. There's such a thing as having your share. I had way less, much less than my share of groupies. But it, ah, kept me satisfied."

He said he spent a lot of his time in hotel rooms watching TV and reading, a pastime that earned him the honorary title of band bookworm, or band heavy. While he was bowing to an addiction to soda pops, some other band members were exploring more questionable vices. Griffith would shun drugs and alcohol until later in his career.

His first recording date with Brown was for the pivotal record "Say It Loud — I'm Black and I'm Proud" in August of 1968.

After several rather forceful hints from militant groups like the Black Panthers, Brown abandoned his "processed" hair style and went natural with an afro. Griffith remembers the occasion.

"We were in the studio getting ready to cut 'Say It Loud.' As usual, the band was in the studio an hour before James got there. We were in there just killing time. We'd wait in there and never know why. And this time we saw why."

Brown then espoused the natural look, but within limits.

"I had the only what you call real afro. In fact he made me cut mine back, 'cause mine was out to here. [Gestures over a foot from his head.) I was proud of mine. I was the only one in the band that looked the part. So James sent it down through channels, down through the road manager that I looked like a wild animal and to cut some of that sh-- down. I still had a full afro, but before I looked like a big bubble-head, big mushroom-head afro."

Quickly, the strong-minded Griffith got fed up with Brown's apparent hypocrisy. Brown would fine band members when they missed a note in the recording studio. Yet he rarely had his performance — and the lyrics — worked out before the recording session. Griffith remembered one time when the band took matters into their own hands.

"During those days you recorded live. There were no overdubs, you know. Before we would record the song, we'd learn it, then James would come in and do it live. Not in a booth, but in the same room with the band. Technique-wise it was funky. Real funky. But it was real live. You could hear it. You could hear the band bleeding into the vocal mike when it's separated into tracks. We had to do these songs over and over and over until James got it right. The band would play it correct every time. You'd pick up a lot of stamina that way."

"That one song 'Give It Up or Turnit a Loose' you hear him say, 'Start over again.' That's where James wanted to start all over again, but we didn't stop. We just kept going."

The spontaneity cut both ways. Griffith found himself on the other end of the bargain on one famous cut, "Ain't It Funky Now," when Brown called out for a solo from the trumpeter.

"Not in my wildest dreams did James call me for a solo. Maceo [Parker, saxophonist] pretty much knew he was gonna get called all the time, so he was always prepared. Not that he needed to, 'cause Maceo could do it off the cuff. Maceo was a player and a real wizard at improvisation. With me, I'd have preferred to have something planned, which I didn't. Now, that solo is a classic. Much to my surprise. It still kind of tickles me to know that anything that I've done has become a part of pop music history, which it did.

Griffith's tenure came to an end by his own choosing in 1970. By then, he was the musical director of the band and making good money. But Brown's personality and his way of running the show ate at Griffith.

"Understand ... I don't mind being quoted ... James Brown is ... mentally imbalanced," Griffith said. "He's insane. The man has a mental problem. I don't want to practice armchair psychiatry, but James Brown's ego was just so large. He would do things to prove a point. He fired Pee Wee just to show that he would fire somebody that was integral to the band. With James Brown — a little of my observation — being that he was pretty much short in stature, had that Napoleonic complex. He had that real bad. Still does to this day."

"When we were with James Brown, Maceo would sometimes take the comedian spot. He was a funny guy. Maceo would end his comedian spot by doing Eddie Floyd's 'Knock on Wood' with the James Brown band. But Maceo started getting too much house, too much response from the audience. Whenever Maceo would start getting too much house from 'Knock on Wood,' James Brown would cut it out the show. He would say, 'Man, we need to stop doing that.' He'd give some lame excuse about it not fitting in, or the show is too long or something. James Brown would not allow himself to be upstaged. Except he could not stop the band from upstaging him."

Brown fired musicians for breaking minor rules. He effectively controlled their lifestyles through regimentation. He instituted pay cuts for dubious reasons. Griffith took great pride in his work with James Brown. But after one paycut too many, Griffith led a mutiny against Brown, culminating in a revolution in Columbus, Georgia, in March of 1970.

"We actually delivered the ultimatum in Jacksonville, Florida," Griffith explained. "Having already anticipated that he would say, 'Well, what would you guys charge me to keep this up,' we already had a price for him. Sol said to him, 'We would do Jacksonville and Columbus for 'this price, or we'll do one or the other for this price.' For a past indiscretion in Jacksonville there was lien on the gate, but James Brown was still going to be brass and be cocky, even when he was semi-crying the blues to us about the lien on the gate. So we played Jacksonville out of the goodness of our heart. We decided that we'd play this one for him and then when we got to Columbus, we — meaning the band — would get together on a price for the Columbus gig, 'cause we're out of here. After the Columbus gig, there was like four days off, or something like that. Then he could make the change. 'We're going to play these dates up to the off days so you can get a chance to do something. We ain't going to leave you stranded,' we said.

"So we got to Columbus and we're sitting there ready to negotiate and James Brown comes in and he goes through all kinds of sh—. He did the pocket play, as if he's got a pistol. In certain walks of life, if you do like that with the pocket of your jacket, it means you've got a pistol. Maybe you got a gun, maybe you don't. So he was all up in Maceo's face like this, challenging Maceo. No, he did it to Melvin [Parker, Maceo's brother and the band drummer]. He always, always had this animosity towards Melvin. So Maceo like, lost it. Maceo and his brother — I found out later his whole family — are like, tight, very tight, very close. So that broke Maceo up to sec James in Melvin's face, acting like he got a pistol.

"Maceo was in the bathroom getting real emotional. He was like at that danger point where a man gets so angry he got tears comin' out of his eyes. Maceo was like, 'Hey man, you'd do that in my brother's face, makin' a play on my brother, man?' At this point, Maceo and I had developed such a bond. In the dressing room, Maceo was like, 'I can't handle this. Man, I can't handle this.' So I agreed with Maceo, 'If he's gonna come that way, let's go kick his a–!' I was willing to go that route. Cause see, we called that, we had a term for that when you started makin' pocket plays, started talking dirty, talking gangster talk — we called it 'gettin' in the grease.' And so we were like, 'All right, if he's gonna get in the grease, we gonna get in the grease with him.'

"I'm sure I did not verbally suggest it, but I alluded to the fact that let's go down, let's go down swingin'. And no question, we would have beat James Brown's a–, real good. Real, real good."

"I was heavier, a lot heavier, younger and a lot stronger. I was rough enough. I was passive, I was really not a violent person, but I had the physical prowess to take care of myself if it were to get into an altercation. All this whole charade and this pocket play, was just a stalling tactic until the other band got there. And the other band ended up being Bootsie."

"There was a knock on the dressing room door [three short raps], 'Yeah. C'mon in.' It was Bootsie. 'Mr. Brown, we're here.'

Brown had quickly arranged for another unit to fly down to Columbus to replace his band. It was led by William "Bootsie" Collins on bass, his brother Phelps"Catfish" Collins on guitar and Clayton "Chicken" Gunnells on trumpet. This band played on several of Brown's next hits, including the smash "Sex Machine." The core went on to join Clinton in Parliament-Funkadelic and Bootsie's own "Rubber Band."

Griffith acknowledged that Brown had pulled a fast one on the exiting band. The group went to the stage and hauled their equipment off to the puzzlement of the assembled audience. The replacement group quickly set up and after an apology for the delay, the James Brown show went on. Later reports said Griffith and the band quit during a holdout for more money. Griffith says there was more to it.

"We had a list. He would have to have met everything on that list, which included more money and different conditions. Such as 'on the band set, butt out. We don't want your input on the band set. In general, on the road, we are adults. We don't need to be treated like no g–d— babies. This regimentarian stuff — on stage, we've already developed our own sense of pride that we are going to do the best we can do. We're going to do a good job and look the part, so we don't need you on us 24 f— in' hours a day lookin' over our shoulder.' He wasn't always physically there, but his edicts and his laws and sh— were. We were like, 'James Brown, that sh—is through. That is through.' We handed him a whole list of demands, not just the money."

One member of the old guard stayed on with Brown, John "Jabo" Starks. According to Griffith, Starks owed Brown money and felt obligated to stay and work the debt off. Despite his "scab" status, the mutineers held no ill feelings for Starks. Brown forgave and forgot as well, as evidenced by the return of many of the musicians in later years.

"I think he directs more bitterness toward Maceo than me," Griffith said. "He always regarded Maceo as real close. 'Yeah Maceo, you almost as big as me,' he'd say. He sort of shared some of the limelight with him by giving him all those solos on the records. Made Maceo a household name.

"But time heals everything. Maceo hasn't really felt any noticeably ill will from James. Plus now in Maceo's case, Maceo is happening more so than James. Maceo is more in demand than James Brown is. There's nothing James Brown could achieve or accomplish by directing ill will at Maceo; And with Zena's I've got a showcase to accomplish what I want to do, so there's nothing he could do by directing it at me. And I saw James Brown on Arsenio Hall last night, so everybody's got their own thing workin'."

Griffith's harsh words about Brown are underscored by a respect for him. Griffith told about Brown coming into the recording studio with every instrumental part in his head. The horn parts sometimes sounded very wrong, but they miraculously worked in practice. Commenting on Brown's recent appearance on Arsenio, Griffith said, "The man's still got it. He's still got what made him famous. He's still on the case." The tension between the band and the energetic, expressive singer led to some electrifying cutting sessions on stage.

"We knew that we were his supporting cast. We were laying the foundation for him. And we wanted to do a real good job. We wanted to do a good job to the point of overkill. We would know when it was overkill when Gertrude Sanders — that was the wardrobe mistress — she would come into our dressing room and say, 'Man, boss is dead. Boss is dead. Y'all done killed the boss. He's dead! Y'all killed him!' And James Brown would be there [panting], his tongue hangin' out. When the band inspired him, he would give 800% on stage. It was like back and forth. 'Do me like that? Oh, you're gonna do me like that? Then I'll do this!' And James would start doing something he hadn't done in a long time. Like doing the splits. Physical stuff. It was like cutting heads, right? And the audience was the beneficiary. There was a sense of pride in the band, knowing that we killed him."

After Brown, Griffith worked with Maceo and All the King's Men, the alumni society of the Columbus coup leaders. The band was well received by the audience, but naivete was working against them. Their association with Brown worked both as an advantage and a disadvantage. On the plus side, the band enjoyed notoriety for their work with James and their flamboyant departure. On the down side, Brown's power helped keep their success limited.

"At this point we had the Maceo and All the King's Men Do Their Own Thing album out, but it wasn't getting very much airplay," Griffith said. "We were getting word from jocks . . . we'd come to different towns to play . . . we were being told that James Brown was paying them not to play our record. He was paying them not to play it! Reverse payola.

"James Brown was still a very, very, very powerful force in the business, especially where airplay and R&B was concerned. James Brown was very powerful. These guys would say, 'Yeah, we play it anyway.' They probably f—in' lyin'. They'd play it when we got in town for the show we were doin' there. When James Brown told them don't play it, they didn't play it. A lot of times, he probably didn't even have to pay them. Soul Brother Number One (he hadn't gotten the title of the Godfather of Soul yet) James Brown done told you not to play this. And just to stay in his good graces, the money wouldn't even have to change hands. That's what I perceived later on."

From that group, Griffith moved to Bottom & Company, a Nashville-based band that contributed several songs to the Motown catalog via other acts. In 1976, Griffith joined Fred Wesley, Maceo Parker and trumpeter Rick Gardner in the Horny Horns. They served as a dash of James Brown-style soul in Clinton's Parliament-Funkadelic project and Bootsie's Rubber Band. Clinton and Bootsie's show featured dirty funk with acid-rock guitars. The bands were noted for their extravagant costumes and elaborate, fanciful concepts. Clinton took his listeners to outer space, to the inner space of the mind and down to the sunken land of Atlantis. For a sketch of this period, we go to Kush's own words.

LMN: Was it as wild backstage with Parliament-Funkadelic as it was on stage?

Kush: Probably backstage it was worse.

[Laughs] LMN: Why? What kinds of things went on?

Kush: Sex, drugs and rock 'n' roll. Always drugs and often sex.

LMN: You've told me how James Brown controlled his band with fines. How did George Clinton control his band'?

Kush: Through cocaine. With cocaine and knowing everybody better than they knew themselves.

LMN: How did he rule the band through cocaine?

Kush: A lot of people were doing it, a lot of us were doing it. And he was the connection. He was the one making sure that it was available. He always had it.

He also controlled us by not paying us much money, which means that we couldn't get much cocaine, so you had to keep it at a moderate level. And a lot of times they had to go through some of his channels on the road to get it. He would always have some. You always knew George had some. That was then. I don't know what he's like now.

LMN: So there was a lot of drug use, there were people under the influence while they were playing?

Kush: Well, you would take your little toke before you went on. The dressing room was always. . . the bathroom was always full of smoke, back in the catacombs of the dressing room, the toilet of the dressing room.

Cocaine was always done secretly, kind of real clandestine-like. Only the select few, the elite, would go back to George's dressing room and say, "Give me a toot Give me a toot, man. Just a few." And there was a lot of joint-smoking on stage, during the performance, in front of the crowd. That was part of what people paid to come and see, see us smokin' dope on stage and more or less thumbing our nose at authority.

George would say, "Hey somebody throw one of those bad joints down here." Bad meaning excellent quality. And it would rain joints on the stage, from the audience. And we would be giving each other a shotgun on stage. They loved it, the crowd loved it. For them, it was a chance to thumb their noses at authority too. We were definitely an underground, subculture-type presentation.

LMN: How was funk different in that band than in James' band?

Kush: They had a very, very heavy acid-rock influence. James Brown was just straight-ahead, R&B, good old soul music. James Brown's stuff was heavy on the horns, Funkadelic music was heavy on the guitar. The Horny horns had our own input into the funk sound, but that was like bringing just a corner of the James Brown sound via the Horny horns to this acid rock influence we got here.

LMN: Did George play keyboards on stage?

Kush: Clinton didn't play sh— on stage. He couldn't play nothin'. Although he could clap his hands in time.

LMN: He wrote the songs, didn't he? Kush: Several. Lot of them he wrote. George was more the keeper and the perpetrator of the concept. He more or less was like, "Here's where we're coming from."

LMN: He wrote the lyrics, right?

Kush: Lot of the real bizarre stuff. . . a lot the musical stuff was written by Gary Shider, Glen Goins, [vocalist] Mud-Bone and Bootsie.

LMN: What did Goins and Shider play?

Kush: They both played guitar. But they were more like vocalists who played guitar, in that they were vocalists first. Glen Goins was a killer. vocalist. And a dynamite songwriter. He used to come in my room at the hotel. He'd bring his guitar and he'd be like boom boom [on the door], "Let me show you something." Then he'd sit down and play some really hip stuff, really nice stuff on guitar. Something that was very unFunkadelic. Very un-Funkadelic and very nice.

LMN: How do you think Clinton was influenced by James Brown?

Kush: You mean musically? That's why he had that horn sound. He liked that horn sound.

LMN: What role did politics have in P-funk and how was that different than in James Brown?

Kush: P-funk was more radical. James Brown sort of like embraced the system. In other words, if you want to change it, become a part of it. Get inside of it. Whereas George was the opposite: F— the system. That's really where George was coming from. We really didn't preach it, but that's what our image was.

LMN: He opposed violence though, didn't he? "You don't need the bullet when you got the ballot?"

Kush: We played some political rallies. We played for Bill Bradley. Or George did. We played a rally for him in Patterson, New Jersey.

LMN: But the sort of messages he put in his songs?

Kush: He really didn't put very many um . . . he pointed out a lot of things. He had a lot of raps about how f—ed up the system was. It was always talking about what the system didn't provide for blacks. George was sort of a black Timothy Leary. Turn on, tune in, drop out. Get high. Realize the system is not for you. Get high, smoke some dope and the hell with it. F— them if they can't take a joke. All you can really do is get high. Get really stoned and deal with it.

Like George would say sometimes, "If you will suck my soul, I will lick your funky emotions." That was sort of like some sexual overtones. In other words, his answer was 'just party.' We know what the deal is. As a people, we know who we are and we know what the system is.

LMN: Some of the lyrics strike me as kind of sexist, especially "Handcuffs."

Kush: Exactly. Exactly! At that time the guys were going around with handcuffs. They'd see a chick and blap, they'd slap them on, "C'mon, let's go." They were kind of like "living out the songs," you know. And the audience, the fans went for it. They loved it.

LMN: What was a conversation with George Clinton like?

Kush: I guess that would depend on who you were.

LMN: Did he put up a lot of facades?

Kush: Um, I. . . George's whole image was "I am going to be a crazy motherf—er and I ain't never goin' to back off of that. I ain't never going to act differently. I'm going to be subculture and radical and crazy."

I was probably a real head challenge for George, inasmuch as I respected him, yet I was a rabble-rouser. I was a champion of the underdog, the guy that did not really know what was going on. I was like, "You don't have to take this sh-. You don't have to take this. What kind of contract do you got?" I'd find out who had a contract and who didn't. I would like more or less predict or calculate what George had made.

There were a lot of guys. . . there' s a song called "Funkin' for Fun." F— it. Have fun, get high, get some broads. They didn't really want to learn about the industry, until it got to a point where the ignorance of the individual was working against them. I'd get them to the point where they were wondering why it is that certain desires weren't being met within the organization. 'Cause you know there are some things in this business. . . there are some facts of life you need to know.

LMN: What kind of conversation would you have with George?

Kush: He would know that I could not be bullsh—ed. And to a certain degree, I may be placated. In a lot of ways, I decided when I would allow to be bought off in cocaine. You could buy everybody off with cocaine. You could buy me off too, but only when I decided. He could buy everybody else off at his discretion. For me it was at my discretion. For instance on the Motor Booty Affair album, I agreed to do the arrangements on this song "I Will Fish Your Waterside." The horn arrangements for X amount of drugs.

So he had his henchmen bring it to the hotel room. But this was not the same sh—that I had tested. So you know how it is, you know about the old switcharoo, you know, working out of two sacks — two bags. George sent something lesser, so he could retain more of his stash. Or, the guy who he sent it with switched. The switch was somewhere.

Clinton somehow guided P-Funk through this very fruitful period in spite of his appetite for drugs.

"He was screwed up a lot, as far as being stoned," said Griffith. "But he was on top of it. He was a power broker. Every label wanted a piece of P-funk. They wouldn't care. . . every agent wanted. . . every member of Parliament could get a record deal. If you were a part of that, you could get a contract. If you were presently a part of it, or if you were initially a part of it, you could get signed. George controlled all of this."

Griffith appeared on every Parliament-Funkadelic album from 1976's Clones of Dr. Funkenstein through Clinton's 1986 solo album Atomic Dog. He stopped touring in 1979 and landed in Los Angeles "because it was too cool to go anywhere else," where he did session work and "slept on everybody 's couch." His drug use continued. Griffith was frank about his cocaine use and admitted to using heroin as well. "But I never mainlined [injected heroin intravenously]," he said emphatically. "If anybody says Kush is mainlining, they lyin.'" In L.A., Kush opened and operated a restaurant inside a film studio with a girlfriend. The couple left under unsavory circumstances in February, 1983.

Back in Louisville, he "cooled out." His girlfriend became his second wife and the two opened a restaurant on Poplar Level Road called the Budget Banquet. Drugs ate up the profits and it soon closed. His marriage and his health began to fail. He hooked up with Herman Anderson to form the Derby City Blues Revue in 1985 and played some dates with a jazz trio called Kush, Clark and White with Riley White and Pam Clark.

The Eighties were a time of deteriorating health. Griffith continued to play music around Louisville. And he continued to use cocaine, which indirectly exacerbated his health problems. Griffith admitted that he ignored the warning signs for diabetes until it was too late.

"The eyes went first, then the kidneys," Griffith recounted. "My vision became kind of blurry. I had never needed glasses before.

Matter of fact, what happened is, I had never had a driver's license before. When I tried to get my driver's license [in 1983], that's what brought my attention to it. I didn't really need to have good vision until I tried to take the vision part of the driving test. They said, "Hey, you're going to need glasses or something. The vision that I was seeing, I was accepting. It was like, 'Yeah, that's okay.'

"I had been seeing the symptoms for diabetes for years. The publicized things like the constant thirst, but I always thought I was just always thirsty. I always liked good stuff to drink. Sores that did not heal in a timely fashion. A lot of the symptoms you see on a bus, on the advertising, or on the cover of a matchbook.

"I lost my glasses and I needed to get another pair and my eyes got tested again for glasses," he went on. "The doctor said, 'Your glaucoma pressure is up. You're going to need to go see a specialist.' So I went to this doctor that was one of the foremost eye doctors in the city. The doctor said, 'You've got a serious problem. You're diabetic. You're developing this retinopathy with your eyes.' So that's when diabetes became an issue. He sent me to an endocrinologist for the diabetes. Meanwhile I was still getting laser treatment.

"Then began the whole blood sugar issue. They put me on a diet and put me on medication. I didn't think it was that serious. And they said at my age, if I were to lose some weight, the diabetes would kind of, in a sense, go away. So I immediately went on a regiment to lose weight. At the time, my wife knew a lot about nutrition, she had a restaurant at the time, so she made sure I had the right kind of meals. I lost the weight. I didn't eat pills anymore, 'cause I lost the weight. In essence, the diabetes was kind of like fading. But by this time, the laser treatment was too late. So the blindness came.

"I immediately started making plans to get social security. I knew it was going to be inevitable, so I put all those things in motion and tried to deal with what was practical. I started making plans for the next phase. Some plans. Not as many plans as I should have."

Worse news was to come.

"They also told me to be on the lookout for kidney failure, 'cause that would be next. They said that's what they pretty much expect is for the kidneys to go. I think what happened is a combination of that and high blood pressure. I had, um, in '87, '88, still been doing big drugs. Not as many as I was doing on the road, but still doing them. I got to the point where I said 'to hell with this' and signed myself to JADAC [Jefferson Alcohol and Drug Abuse Center]. I was in there just three days when they rushed me to Humana for blood pressure at stroke levels. Like 210 or something. And for most of the time I was supposed to be at JADAC, the first two weeks that I signed for at JADAC, the first ten days or so I spent in the hospital for blood pressure problems.

"The doctors told me that my renal functions were going. That I was inevitably going to need dialysis. So that really bummed me out, to the point where I decided. . . they said, 'You know, you need to start thinking about where you want the shunt put in for access for dialysis,' my initial decision was, 'F— that.' I had chosen just to die. I said 'to hell with this.' So I asked them what would happen if I didn't take dialysis. I asked about the pathology of dying from uremic poisoning. What would I experience and such, to let myself prepare for that. There was just something about. . . I didn't like having some modification in my damn body to facilitate the machine. That didn't sit well with me. I was like, 'F— that.' That was my original decision, to just croak."

What changed his mind? "I started thinking about how that would affect the other people in my life," Griffith said. "In short, for one time, one of the few times, I thought about somebody else rather than myself. 'Cause I'm a pretty self-centered person. Always have been. It's one of my character defects."

Once an overweight man, Griffith now weighs 157 1/2. He last weighed this much when he was 12.

"The strange part is when I lost weight I did it in a manner. . . I didn't tone up while I was losing it," he said. "So I've got all this loose flab hanging. That's the strange part about it. Another strange part is, I now have sex appeal. I'm more physically attractive to more women. So they tell me. I'll take their word."

More than one fan has found Griffith's story inspirational. Aside from his coping with kidney failure and blindness, Griffith amazes some with his ability to give 100% on a stage much smaller than he was accustomed to. As one fan in the know exclaimed, "If he wasn't disabled, he's still be on top. He's that good."

The 44-year-old Griffith shrugs this kind of talk off with characteristic practicality.

"What they perceive as inspiring is what I call going on with life," he said. "They make more of it than I do. This is reality, this is what it is. I could cry and gnash my teeth and wish it were not so. But it is. To me it's just not a big deal to look at it for what it is, although I have my moments. Go ahead with life. But to a lot of people that I have this conversation with, it's just real inspirational, they are really just touched by what they see as determination. Stick-to-itiveness."

Three years ago, he reunited with Smoketown Red to form Kush and the Sunstroke Blues Band. The group underwent numerous personnel changes before settling into today's lineup. While the group has no definite plans to record material, Kush is excited about the band's prospects.

"The unit I have now is pretty much set," said Griffith. "It will probably be the unit that will go on the road. If I decide to do something monumental, this will probably be the unit. I've got some more shaping to do, because they have not been a recording unit. They've got a long ways to go before they are ready to record. But before that I intend to extend our circuit a little bit. Do some traveling. Take it on the road a little bit. That may be in this next year, the coming year."

A typical Sunstroke set is heavy with blues standards, veering into R&B, rock and funk as the situation — and the clientele — demands it. "The paying customer's always right," explains Griffith. In addition to classics by Muddy Waters, Jimmy Reed, B.B. King and others, the quartet plays medleys of James Brown songs, Sly Stone songs, '50s rock songs and "a Kansas City medley," all arranged by Griffith.

Griffith is clearly the main impetus behind the Sunstroke Blues Band, giving the band structure and guidance, as well as the benefit of his considerable professional experience. But without Zena's Cafe, the band may never have gotten this far.

"Zena's been berry berry good to me," Griffith joked, briefly picking up the accent Saturday Night Live's Garrett Morris used in a skit about a Cuban baseball player. "it's been a place where I can pretty much remain visible and keep my ego stroked, which is important to an egomaniac like myself. The fans have been very supportive and loyal. And the owner, Mary Jean Zena, aside from being a sound business person, she and I have become over the years just really good friends. She's been a real good friend to me. She's made it possible for me to remain visible and employed, even though it's not the level of money that you make in the Big Time — obviously.

"Being at Zena's and working for Mary Jean has made being at home and being in Louisville okay. She's made it real tolerable. She's a real sweetheart. And the club, Zena's, the ambiance, the atmosphere is just so right for what we do.

"Sometime in the not-too-distant future I'll have to leave there. But I'll always look at it as home. I'll probably always consider it our home base. And should this group really make headway, traveling, she will always be in consideration. If we're out there happenin', I'll always be willing to come back and do something with, or for, the club. And if and when I ever write an autobiography, Zena's will get a lot of space. Probably a whole chapter."

Griffith said that while he doesn't dwell on it, he senses the clock ticking. He often misses dialysis treatment and strays from his diet. He smokes cigarettes.

Three times a week, for three hours and 45 minutes a day, Griffith undergoes dialysis at a local hospital. His blindness prevents him from doing much session work, which requires sight-reading music. That hasn't kept colleagues and music business associates from calling him with offers. Possible projects include producing a hip-hop act, producing an R&B chanteuse in L.A., writing a Broadway musical with a local artist and lending his vocals and trumpet work to ex-bandmates' recordings. From December 22 to January l, Griffith will be on tour in Europe with the Bobby Byrd All-Stars, a James Brown band offshoot featuring Louisville saxophonist Willie E. Little and several members of Byrd's family. The tour will climax with a New Year's Eve show in Paris with Brown alums Marva Whitney and Lyn Collins.

So in addition to having an enviable past career in the music business, Griffith seems to have a promising future. Unless he retires.

"I'm committed to Sunstroke," Griffith said. "But I'm being asked to lend my allegiance here and there. 'Let's get together' and 'I need you to do this.' I'll do it. It's just a matter of juggling my time. But I keep thinkin', 'You'd think they'd leave a blind guy alone. Old guy. Just let him fade into the sunset.' But they won't, for whatever reason. I don't know if it's camaraderie over the years, or they think that much of my ability or possible contribution I can make.

"At this point, I'd like to just retire. It's that laziness coming out in me. Every once in a while the lazy part of me flares up and I get that real strong urge to live on that mountaintop that I talked about. Go into a cave and just kiss the world goodbye. Forget about it. Just leave me alone. Let me forget about it," he said.

Would he take his trumpet? "Uh, yeah, 'cause it goes with me, you know. I may not play it, but it's just part of my luggage," Griffith said in typical under-statement.