social bookmarking tools:

|

|

| Available RSS Feeds |

|---|

- Top Picks - Top Picks |

- Today's Music - Today's Music |

- Editor's Blog - Editor's Blog

|

- Articles - Articles

|

Add Louisville Music News' RSS Feed to Your Yahoo!

|

Bill Porter

Legendary recording Engineer ... and Teacher

By Jean Metcalfe

"Who knows I'm on this airplane," Bill Porter wondered when he heard his name paged as the aircraft touched down in Boston.

"Nobody," he said to himself.

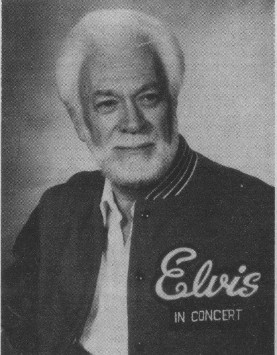

The date was August 16, 1977, and Porter was on his way from Miami to mix the live sound for Elvis Presley's upcoming tour scheduled to begin in Portland, Maine, the next day.

Dialing the first of two Miami phone numbers handed to him at the airline counter, he was greeted with a recorded message: "The number you have reached is no longer in service."

The second number brought the father-in-law of Porter's son on the line.

"They probably wanted to tell you that that singer Elvis Presley died," he said.

It must have been Presley's ailing father who had passed away, Porter thought.

"You sure?" Porter pressed.

"Yep, I'm pretty sure."

The look on the airline employee's face confirmed the gentleman's message. She told Porter she didn't have the heart to tell him herself.

Deciding to continue on to Portland to be with the other tour members, Porter found himself seated alone on the outbound plane during the 90-minute layover. The stewardess' instructions had been to "put this man in first class and give him whatever he wants to drink."

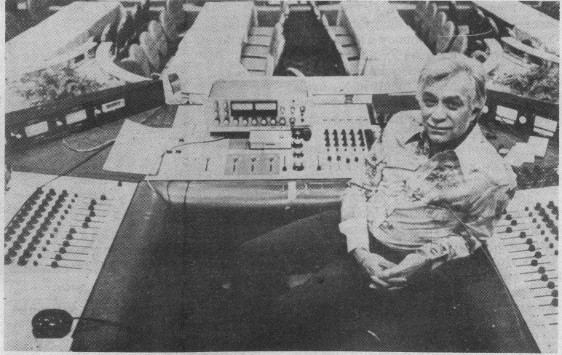

"When you're kinda by yourself it hits you pretty hard," Porter related as we talked in his office at Allen-Martin Productions in Jeffersontown, where he has served as president since 1989.

"There wasn't anybody to talk to, and all of a sudden I'm thinking about what's going on. And you reflect on a lot of things: How your life's going to change and how you're going to miss all the activity and the people ... and it's a big hole."

It was nearly midnight two days later when Porter found himself being escorted by Elvis band member Charlie Hodge to Presley's open casket, which had been placed in the rearranged dining room in front of the archway leading into the music room at Graceland.

"[Hodge] takes me over to the casket ... [Porter paused for one of the many deep breaths he would draw during the recounting of the events] ... just like a proud father ... and tells me ... how nice Elvis looks ... ."

Porter was asked by Elvis' record producer, Felton Jarvis, to record the funeral services, to be held the following day.

"[I]t was kinda hard ... they're crying the whole time [the service] is happening."

As Porter expressed his condolences to the Presley family at the end of the services, Elvis' father, Vernon Presley, said to him something he has never forgotten:

"Bill, you recorded the last concert. Elvis would have wanted it that way."

Porter's quiet voice was heavy with emotion as he assessed the words:

"Pretty heavy statement."

Fearing someone might "rip off" the recording of the funeral service, Porter held onto the reel-to-reel tape. He called every recording studio in Memphis in an attempt to have a copy made for himself, but, Porter said, "they wouldn't touch it with a ten-foot pole. Would not."

That night Porter returned the tape to Graceland at the behest of Hodge who related that Vernon Presley "is paranoid," and that he had said, "That tape gets out to anybody, I'm gonna kill 'em."

Today Porter still wishes he had a copy of the tape. He wouldn't feel guilty "because I'm not the kind of person that would ever do anything with it [capitalize on it]. Just to have it myself."

Are the details of the Elvis years and the funeral still vivid?

"Very. Most people don't know this, but Elvis Presley and I many times had conversations alone. Just he and I. And so it was more than an employer/employee thing, it was a friendship. Not many people can say that."

Porter wishes he had a photograph of himself with Elvis Presley. Three times in Las Vegas they set up photo shoots and three times something happened that forced them to cancel.

Of the gifts given to him by Elvis, Porter is probably proudest of the ID bracelet that has "ace engineer" on the back of it and Porter's name on the front.

Porter also has the last microphone Elvis used: "I know this was the last microphone he used. I know that."

Although Porter worked with some of the most successful singers in the business, he didn't aspire to a performing career himself. He did sing in the boys' chorus in school, but didn't do solos ["I earned a letter singing, not that that's a big deal"], and he said he "tried to play trumpet."

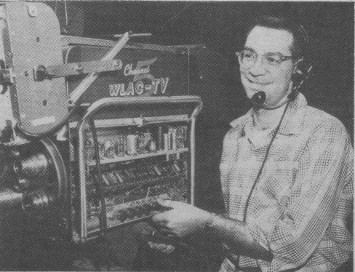

Bill Porter graduated from East High School in Nashville, and studied electrical engineering at the University of Tennessee. After working for several years as a television repairman at Motorola, he moved on to Nashville's WLAC-TV where he worked in audio, video and maintenance. It was while working at the television station that Porter heard that RCA was looking for a new engineer. RCA's "easygoing" Chet Atkins had had a fight with engineer Bob Ferris ["the kind of guy who can make anybody mad"], and Ferris had lost.

Thinking Atkins would select Ferris' replacement, Porter would show up at RCA each day after finishing his 4:30 a.m.-3:00 p.m. shift at WLAC.

After nearly two weeks, "I believe the girls in the office got tired of me coming over there" and apparently persuaded Atkins to step out of his office and speak with Porter. Atkins agreed to put Porter's name on a list of applicants to be interviewed by Bill Miltonberg, RCA's head engineer from New York.

In an amazing string of coincidences, Porter was hired by Miltonberg, but not before he had been warned by an older (and presumably wiser) engineer from New York, who first interviewed him:

"This business is going to kill your marriage. It's gonna wreck your life."

While fulfilling his two-weeks'-notice obligation to WLAC, Porter spent his evenings at RCA "trying to figure what's going on." Ferris was busy engineering the many artists who wanted to get session work done with the experienced engineer. On his last day at RCA he took time to teach Porter how to cut a disc and do all the other things that would be expected of him. The following morning Porter found himself staring at a console with twelve microphones.

"I panicked. I really did. ... See, the most microphones I ever worked with at the TV station was four," he chuckled.

"So Chet stuck his head in the control room a couple of times that first day and said, 'You having problems?'

"I said 'Yeah.'

"He said, 'I kinda thought so. I'll help you work it out. Don't worry about it.' "

Porter soon engineered a session with Don Gibson, recording "Lonesome Old House," a song that landed on the charts the first week, peaking at No. 11 on the country charts and No. 71 on the pop charts.

About two months later Porter engineered "The Three Bells" for The Browns and it subsequently hit No. 1 on both the country and pop charts.

"First million copy seller," Porter said with justifiable pride.

"Chet helped me a lot, though, kinda getting myself organized, you know, and then he kinda backed off and let me alone."

Atkins would later videotape an introduction for a black-tie affair in October of 1992 at which Porter was inducted into the prestigious Mix Magazine Technical Excellence Creativity Award Hall of Fame — one of only fifteen so honored in its ten-year history. (Atkins couldn't be there in person as he was performing at Carnegie Hall.)

At RCA Porter engineered Top 10 records for Bobby Bare, The Browns, Floyd Cramer, Skeeter Davis, The Everly Brothers, Connie Francis, Al Hirt, Hank Locklin, Bob Luman, Bob Moore, Roy Orbison, Elvis Presley, Jim Reeves, Tommy Roe, Ronnie & the Daytonas, Sue Thompson, and Johnny Tillotson.

After leaving RCA in 1963, Porter worked for a short while as a recording engineer at Columbia Recording Studios in Nashville, and co-owned and operated (with Anita Kerr) Poker Music Company, a publishing company in that city.

The years 1964-66 were spent at Monument Recording Studios in Nashville, which Porter co-founded.

From 1966 until 1973 Porter owned and operated United Recording Studios in Las Vegas, and recorded such artists as Louis Armstrong, Glen Campbell, Harry Belafonte, Diana Ross & the Supremes, Sammy Davis Jr., Pat Boone, Barbra Streisand, Paul Anka, Wayne Newton, Frankie Laine, Gladys Knight & the Pips, Buddy Rich and Bill Cosby.

Later, when the studio was not doing well, Porter removed himself from the payroll and took a moonlighting job as sound man at the Dunes Hotel's Casino de Paree. Presley came to the show one night in (probably) 1968 and he and Porter chatted briefly as they were leaving. It was their first meeting since Porter had left RCA.

In late December of 1969 Elvis telephoned Porter, asking for help with the sound system at the Las Vegas hotel where he was appearing. Among other difficulties, the monitors weren't working and Elvis couldn't hear himself.

After several revisions by Porter, Elvis gave the new setup a try:

"My god, I can hear, it's great," Elvis said.

He wanted Porter to mix his shows for him but there was a problem: the Dunes was a union hotel and Porter was not a member of the union. Presley said he'd take care of it — and he did.

"Well, the first night, of course, I knew nothing about live sound. And I learned about feedback in a hurry [we both laughed] as you can imagine."

"In the first few minutes?" I suggested.

"You got that right," Porter laughed heartily.

The success of the evening's sound (Elvis received compliments from several show-business heavyweights backstage after the show) prompted Elvis to tell Porter, "Bill, you've got a steady job."

"They were starting the latter part of January to go through the entire month of February. That's the way they usually worked it. Four weeks, two shows a day, seven days a week, straight through." Porter laughed and shook his head. They did about four tours a year, he said.

Someone once called to Porter's attention the fact that Elvis' "Good Luck Charm," which Porter had engineered, was Presley's last No. 1 record until he took "Suspicious Minds" to the top in 1969. "Suspicious Minds" was the very first record Porter had engineered for Elvis since "Good Luck Charm."

In 1975, Porter accepted a position as an assistant professor at the University of Miami, Coral Gables. While there (he left in '81) he developed an undergraduate recording engineering program, the first four-year program of its kind in the United States.

"When I went back to Miami after the funeral was over with, it really hit me, because my income took a 60% cut just like that. Overnight."

It was a particularly difficult time, Porter said, compounded by the fact that he was also in the process of getting a divorce from his wife of 27 years.

"It was kinda rough. I remember a couple of times at the University [of Miami] some of the faculty members would take me out to eat [Laughs] because I didn't have any money.

The summer after Elvis' death, Anita Kerr's husband hired Porter for a month-long stint as an engineer at Switzerland's 1978 Montreux Jazz Festival. Although the conditions weren't the best (his hotel was about a mile and a half from the festival and he had to walk back and forth), Porter got high marks from the engineers in France for his live mixes to Radio France:

"How do you get a sound like you do? Man I can't believe how good it sounds . . . stereo's fantastic."

After leaving the University of Miami because of the climate and other considerations, Porter worked in marketing and distributor training at Auditronics Corporation in Memphis from 1981-82.

From 1982-84 he was assistant director of television operations for Jimmy Swaggart Ministries in Baton Rouge, Louisiana. While working with the Ministries, Porter assisted in the audio design of their $10 million television production facility.

In 1985 Porter took a position as an assistant professor in the college of music at the University of Colorado in Denver. He accepted his present position as president of Allen-Martin Productions in 1989.

At my request, Porter looked back over his career and recalled some of the good times, bad times, and interesting times.

There was the night when he developed food poisoning in the midst of a recording session, but had to continue.

"Had to. . . . There was nobody to take my place. . . . I got so sick I couldn't see the VU meters from the console. It was like it was all run together."

And he admitted there were times when he felt like quitting the music business:

"Many times. Many times I felt like quitting. Yeah."

Then, taking a deep breath, he spoke in a quiet, rueful voice:

"I guess to reflect back on the past ... this is in the mistake category ... I probably put way too much of my time in the music business initially, because I wanted to accomplish something, I wanted to make a name for myself."

He continued softly, "I grew up on the wrong side of the tracks. My father, even though he was in pro baseball, he drank a lot and basically the family went downhill. So I felt I had to prove something, so I got this opportunity and I went at it."

Mumbling something about the value of hindsight, he added, "My kids say, 'No, Dad. Nonsense,' but I feel to a certain extent that I lost a lot by not being there. And I know it wrecked my first marriage as a result of that."

The RCA engineer had been right.

"Absolutely, I was married to the lady like 27 years. I lived with her 25 of the 27, but the bottom line is she started to resent me.

Porter, a handsome, tanned distinguished-looking gentleman with snowy white hair and a beard to match, is just a tad past 60 and is single.

There are three children from his first marriage. The oldest son is a flight controller at FAA California; his daughter is married to a doctor in Chattanooga (Porter's first wife lives with them); and his youngest son, a lawyer, is in politics in Nevada.

The proud father spoke of the younger son's accomplishments in the just-concluded Nevada state legislature, where he was successful in his attempts to prevent the governor's personal physician, Elias Ghanem, from being appointed to head up the state's health care program.

"Well, Gene remembers me talking about Elias Ghanem, because he [Ghanem] gave Elvis drugs all the time. In fact, numerous times he flew them from Las Vegas to Memphis for him. ... Elvis gave Ghanem a Mercedes — that's the kind of guy he was."

Gene Porter was challenging Ghanem in a hearing, when "all of a sudden the doctor realized: 'Porter.' And he puts it all together and [Gene] said [Ghanem] got as white as a sheet." [Chuckles]

"Gene was able to ... get the thing restructured where there's now five people running the medical system ... and they're calling this thing the Elvis amendment."

We laughed and marveled at the round-about father-son connection to Elvis.

"So you put the blame on Ghanem?" I said.

"I saw it. I saw it," he said emphatically, his voice rising. "And Gene remembered me talking about that. See, he was only a kid at the time, ten, eleven, twelve years old, something like that."

I expressed my understanding that it had been Elvis' "Doctor Nick" [Dr. George C. Nichopoulos], who had kept his famous patient supplied with the unusually large amounts of drugs to which he had become addicted.

Porter agreed that mine was a widespread belief, but insisted it was an erroneous one:

" [I]f that were the case, they would've taken Dr. Nick to court."

While living in Memphis in 1982, Porter recalled, Dr. Nick had asked him if he would testify at his trial if it came up. Porter had replied, "Absolutely."

"Now I know for a fact, see, Dr. Nick tried to straighten Elvis out. Three times Elvis fired him, during the period of time I knew him, because he wouldn't do what he wanted. But each time Elvis had to hire him back because Nick was the only guy who could straighten him out enough to make him function. Now the last couple of years, if Dr. Nick couldn't go on the road with us, his head nurse went, I mean, just like a personal valet — was with Elvis all the time — just to be sure that things would stay halfway together so we could finish the work. It was pretty bad.

"I remember one time asking Dr. Nick — this was in Vegas — I said, 'What could we do to straighten Elvis out?'

"He said, 'Six feet of dirt. That's all that's gonna do it.'

"I said, 'You're kiddin' me.'

"He said, 'No, Bill, I'm sorry, that's the only thing that's gonna do it.'

I told Porter that I wanted to believe it was the extreme pressures brought about by Elvis' fame that caused him to resort to, and abuse, prescription drugs. Was that the reason, I asked.

"I think so," Bill replied. "I heard a rumor that somebody introduced him to drugs when he was in the army (in Germany). I don't know if that's true or not."

"He had a problem, I know that, because he'd ... get so upset about going on stage. He told me one time ... 'I've got butterflies in my stomach until that first song is over.' ... 'As many times as I've done it, I have that anticipation.'

"And we'd do a tour, and he'd have trouble going to bed. He'd get so wired over a show ... and he'd have to get up the next day and go do it again, and they had to give him pills to knock him out. ... Of course, he got immune to it after a while, and [would] take a little bit more, and they'd have to give him stuff to get him up to work the next day, so it became a vicious cycle. It evolved into that."

Porter said that he didn't see Elvis' drug use as a want but rather as a need "but it grew to a different level because be got addicted to it. Now the statement of 'prescription drugs' is accurate, but Dr. Nick controlled that. So at least he had some control over his body, but this Dr. Ghanem, he just, anytime he [Elvis] wanted them ... ."

Elvis Presley was the artist who was the most challenging to work with, Porter said, and the sessions were always tense.

"We'd start at about 8:00 o'clock at night and work till 7:00 in the morning," Porter related.

The artist who was the most fun to work with was Rusty Draper, who had hit songs on Monument in the fifties.

"Rusty Draper was a phenomenal person to work with," he said. "In the studio he was just fun. Always vivacious and happy and just bubbling all the time."

Said Porter, "The Everly Brothers were fun to work with, too." Years later, Porter and his son Gene went to a performance by the brothers at the Hilton Hotel in Las Vegas where they had been provided seats up front.

"So about halfway through the show, [Don Everly] stops the show and introduces me to the audience, and just flat out he said, 'We were a bunch of young punks and this man took the time and trouble to listen to us and help us create what we were.'

"So he had me stand up [Porter said in a self-effacing way] and introduced me to the audience. My son, of course, ate it up."

Bill Porter's career has indeed been an illustrious one. He has engineered more than 7,000 recording sessions, resulting in 579+ Billboard chart records, with 15 on Billboard's Top 100 chart in one week in 1960. Forty-nine were Top 10, eleven went to No. 1, and 37 were certified gold records.

He was the sound engineer on more than 2,700 live concerts, the first engineer to use all condenser microphones on a recording session, and the first inductee in the Audio Hall of Fame.

His resume is, well, stupefying.

In March, Porter put together "a little dog and pony show" (a video presentation) in Nashville, which highlights his 49 Top 10 records. In it he plays parts of the songs and tells stories. He had invited Chet Atkins, and they reminisced and reminded each other of things that happened on sessions they worked on together that each had forgotten. Chet told Porter, "We had a blast doing that."

What, then, is the part of his career that Porter is most proud of?

"Well, it's interesting ... . People ask me that a lot. ... Obviously I'm proud of records I've done, I'm proud of the recognition I've gotten. But I think, 'Well, is that important?' Yeah it is. But what's the most important thing? And I'll tell you, it's because I was a teacher. Now I've affected more people's lives by doing that than by the music business."

Two of his former students at the University of Colorado now work at Allen-Martin. Another, a junior at the time Porter left, once said to him:

Thank you for teaching me a skill, but most of all for teaching me a lifestyle."

"The lifestyle I tried to teach was quality and responsibility."

"[Teaching] is the only thing I can leave behind, I think, that has any kind of credibility."

Was there anything else that he would like to have brought out in the interview?

"I guess when you get right down to it, I felt like I had accomplished a lot and made a name for myself way before I worked with Elvis Presley doing live sound. But it's interesting how smart I got after Elvis hired me. You know what I mean?"

I did. "Do you mean like the child whose parents get a lot smarter as he gets older?"

"You got it," he chuckled.

"So to a certain extent I guess I sorta resented that. But then, by the same token, if I hadn't had the opportunity I wouldn't have had the exposure, and so forth."

I asked Porter a question I had often wondered about: "Do you sometimes get tired of being Engineer to Elvis?"

"Uh huh. Uh huh." I really do. Honest, I do."

I complimented him on his candor.

"I'm my own person and I have a lot to offer. I always have had. The Elvis Presley contact made it easier. But I just get tired of being Elvis' engineer ... I'm me."

In his present position at Allen-Martin, Porter is frequently called upon to straighten things out in recording sessions.

"And the guys are just blown away with what I do with recordings. And I'd like to do more of that. I don't want to get into being an engineer in the studio. But producing some stuff ... I've already proved I can do it. ... every time I do something and send it out, people say 'My god, what kind of sound are you getting back there?' "

Recent examples of Porter's studio work include sessions with local musician-singer-songwriter Turley Richards and working on an album project for the Middletown Christian Church. Porter received high praise for both projects.

"It's very unusual," Porter said of the Middletown Christian Church album. "You'll swear up and down it wasn't done here, because it doesn't sound like anything that ever came out of Louisville. Does not. Production, arrangements, performance — the whole thing."

"And I know, Jean, I've got something still to offer. But since I haven't been doing it for a long time, people don't think you can. But I can guarantee, every time they call me back there to work on a project, the boys [say]: 'I don't know how you do what you do. You hear things different than everybody else.'

"I want to, quote, produce an artist. They give me the product, but I want to be more in control from beginning to end. And they usually give them to me to fix the problems. Why not fix them before you start?"

Expressing my own personal belief that the valuable experience of the older worker should be utilized rather than shoved aside, Porter reacted strongly:

"Amen," he said, "Exactly right."

Porter was running late for an appointment but he took a few minutes to relate a Billy Ray Cyrus story.

"Billy Ray got off the ground because of what we did here (at Allen-Martin). ... We didn't get the recognition for it. ... We did two songs, got 'em on two radio stations, got a whole lot of things happening, then the manager who was supposed to be doing something ... called me, and, boy, he chewed my rear end out: 'Whaddya mean doin' this?' ... And Ron (Cyrus, Billy Ray's father) told me the guy wasn't doing anything. So then he ... got a record deal. They copied our production to a T on two songs that we did here. Right to a T."

He couldn't recall the song titles, but when I suggested "Wher'm I'm Gonna Live?" and "Could've Been Me," Porter said they were the two done in Allen-Martin's studio.

"They copied the arrangements we did exactly. ... They copied them ... the same arrangements, the same kind of sound."

I expressed concern about quoting Porter's allegations.

"[I]t's okay, because [Billy Ray Cyrus] is starting to allude to it a little bit now."

Porter continued, "I took the tapes up to Eastern Kentucky (before Cyrus got a record deal) and got 'em on the air. We stayed for the show that night and ... I videotaped it. He's looking at me in the camera ... [and saying] 'You're gonna make me a star.' ... That backs up what I said about doing it, you know. He's telling me and everybody else ... but that's the way the business is," Porter said with resignation.

"Well, I hope that they don't put you on a shelf," I said to Porter as I prepared to leave.

"I'm not gonna let it happen. I'm gonna wear out. I ain't gonna rust out."