social bookmarking tools:

|

|

| Available RSS Feeds |

|---|

- Top Picks - Top Picks |

- Today's Music - Today's Music |

- Editor's Blog - Editor's Blog

|

- Articles - Articles

|

Add Louisville Music News' RSS Feed to Your Yahoo!

|

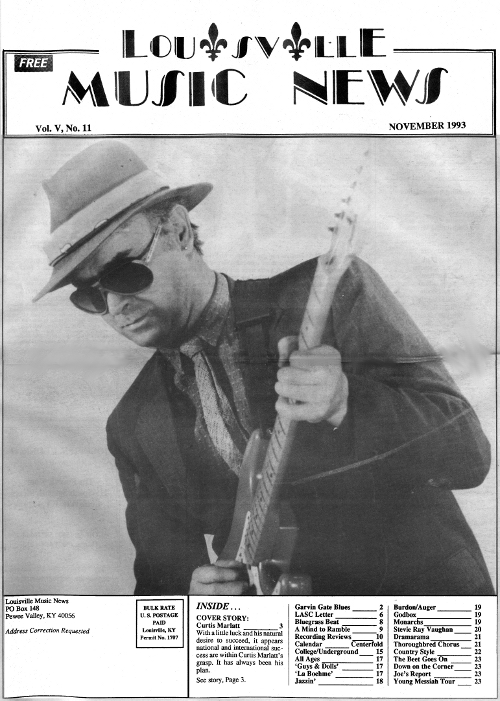

Curtis & The Kicks

By Kevin Gibson

Life is filled with irony and tough breaks and Jonathon Curtis Marlatt has seen more than his share. Much more.

It is this, however, which has formed the native Louisvillian into the spirited, driven perfectionist that he is. It is also this irony and a few particularly tough breaks which make him perhaps the best around at playing the blues.

One thing is certain: when Curtis Marlatt sings the blues, he knows what he is talking about.

Even more ironic is that it was perhaps Marlatt's time of greatest failure which has brought him his most recent success as leader of Curtis and the Kicks. The band formed in 1982 almost by accident and, after one successful local CD and with another on the way, it appears Marlatt's luck has come full circle.

He and his band are currently touring states from Florida to Minnesota and just about all spots in between. With a little luck and Marlatt's natural desire to succeed, it appears national and international success are within his grasp. It has always been his plan.

"My goal is to become a regional band, a national band and then an international band," the 45-year-old said. "All of a sudden my destiny is back in my hands. Nothing will stop me. I'm driven that way."

The story of Curtis and the Kicks could be a blues song in itself. Walking through his Highlands neighborhood one afternoon, a down-and-out Marlatt stumbled upon a group of carpenters busily hammering and sawing away at an old Bardstown Road building. He asked them what they were working on and they told him a blues bar was to be opened there soon.

After having lost nearly everything – his band, his girlfriend, his money — it was as if destiny had led him to the spot.

"I walked in there, found the owner and went up to him and said, 'I've got a blues band and I'd like to play here.' I didn't have a blues band at all," Marlatt said. "He gave me a date, though and that was the birth of Curtis and the Kicks."

That hollow structure later become Fat Cat's blues bar and the imaginary band Marlatt spoke of soon become reality in bassist Butch Ellis, Gary."The Grizz" Grizzle on drums and vocals and Keith Hubbard on keyboards and vocals.

Marlatt's once-depressing existence which had him dropping from a successful guitarist to part-time waiter, painter, etc., suddenly rocketed him back into the world of music, his first love. After 10 years of hard work and dues-paying, the band's first CD, Something's Wrong, got good reviews last year.

Now another CD is in the works, out-of-town gigs are increasing and a European tour is on the horizon. The band has received responses to Something's Wrong from as far away as New Zealand, Poland, Australia, Mexico, Canada, Yugoslavia and more.

But, just like in the blues, it hasn't come easily. Not by a long shot.

As a boy, Marlatt grew up liking the usual boy things, such as sports. And music. It wasn't until 1962 that a 14-year-old Marlatt was seduced by the guitar. A friend of his drum-playing older brother, Michael Rees, who is now a successful artist in California, wowed the younger Marlatt with some licks on a baritone ukulele.

"I was real impressed with this guy," Marlatt said. "He whipped this little four-string out and made it talk."

It was fate and necessity that put him onto the guitar, he quipped: "I don't think my parents could have stood to have another drummer in the family. I know my neighbors couldn't."

Soon afterward, Marlatt's mother bought him a catalog-order acoustic six-string which cost all of $10 and a long, passionate romance began. He began by playing mostly folk tunes, until one day another musical epiphany took place in Marlatt's life.

The young musician-to-be heard a song called "I'm Not Talking" by the Yardbirds, featuring a young Jeff Beck on guitar.

"That was the song that made me want to put down the acoustic guitar and pick up the electric guitar and go out and be a rock star," he said. "I still think, to this day, no other rock band has that kind of energy."

Along with practicing guitar, Marlatt went to St. Xavier High School, where he excelled in baseball, swimming and track, even holding the school high jump record for a while. He did well enough to earn a swimming scholarship to the University of Kentucky and it was on his swimming and schooling which he focused most of his attention.

Still, the lure of playing guitar was in the back of his mind and he began playing publicly with his college friends at parties, just to pass the time. Soon, he and a group of others formed a band called Alphabetical Order in 1967. He was then both musician and athlete, a paradox if ever there was one.

"I was like a walking enigma on campus," the broad-shouldered Marlatt remembers.

"I was starting to get hip, growing my hair long. There were only five hippies on carnpus then and I knew every one of them. I was walking around with my long hair and this great big Kentucky letterman's jacket."

Even as he was lettering in swimming as a freshman at UK — training for the Olympics as well, before just missing the cutoff — it was already apparent to him that his passion was turning toward music.

He returned to Louisville the summer after his freshman year. It was the Summer of Love in America, a summer of music, love and drugs for teenagers everywhere and Marlatt embraced it with affection.

"It was a wonderful period," he said. "It really was the summer of love."

Some musicians from Alphabetical Order contacted him about starting another band and Marlatt was eager. That band was a Louisville mini-legend by the name of Stonehenge. The acid-rock band took off immediately.

"It took us all by surprise how big the band became so suddenly. We were so in awe of everything that was happening to us. Everything was happening so fast and so perfectly. That's when I realized I wanted to be a professional musician. Things like going to school and swimming didn't mean anything anymore," he said.

Marlatt began researching the roots of the rock music he loved so. He began buying albums by blues legends Albert King, Howling Wolf, Muddy Waters, Otis Rush and Buddy Guy. He experienced Chicago blues, then went back to the pre-war Delta blues and Charlie Patton, Son House and Blind Willie McTell.

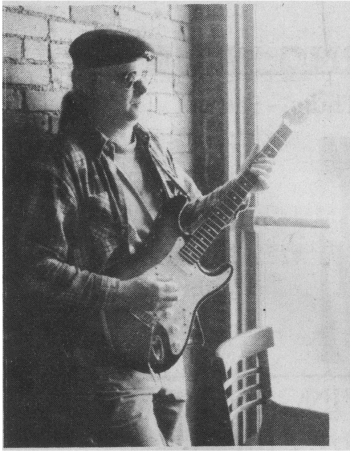

For Marlatt, who still offers reminders of that Summer of Love with his ponytail and black beret, it was one of the greatest times of his life, opening for bands like the Grateful Dead, Steppenwolf, the Doors and Blue Cheer.

Unfortunately, that summer also meant the involvement of U.S. troops in Vietnam. By the spring of 1969, Marlatt had been drafted into the Army. Marlatt, like so many other young men of the period, did not want to go. He tried to create a fake medical history of migraine headaches with the help of a local doctor. It almost worked.

"By then, they were taking more people because they were losing so many more," he said. His story is a chilling one. When he reached the end of his physical, the military doctor was indecisive about Marlatt's eligibility. The doctor sent him to a nearby hospital for tests. Marlatt returned with the results and the doctor made what amounted to little more than a flip-of-the-coin decision.

"It's the doctor at the end of your physical that actually puts you in the army," Marlatt said. "He opens up my results and says, 'Hmmm, well, all right.' He opens the door and there's a bus waiting. The next thing I know, I'm chugging out to Fort Knox."

Marlatt, the epitome of anti-establishment at this point of his life, was disturbed by this turn of events. He went from being a regional rock legend to being just another soldier in the war in just minutes.

"I was sad and angry because so many of my friends were getting out of it," he recalled. "There were so many dark things bubbling up at that time and these forces collided head-on for me."

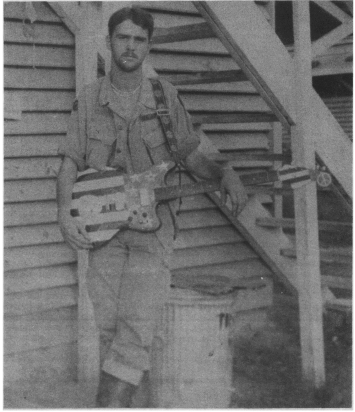

But, he said, "I took my guitar with me. I wasn't going to let anything stop me, after [the success he was enjoying] was snatched totally away. I felt so raped."

As he watched the scenery zoom by on his trip to Fort Knox, he had no idea what his role in the army would eventually lead to, not just emotionally and psychologically, but musically as well.

In basic training, Marlatt met a man named Jim Pokowski, who was the drummer for Detroit's The Amboy Dukes. Pokowski was shipped off to fight and the two kept in touch casually through letters. The chances of the two every meeting again were almost zero.

Soon, however, Marlatt's orders came. His station in the Central Highlands near Qui Nhon, he knew from Pokowski's mailing address, was near his friend's station.

When he arrived in Vietnam and was told of his exact destination, Marlatt realized he and Pokowski would be not only in the same station, but in the same company. And the same platoon. When Marlatt arrived and was shown to his quarters, he looked down at the bunk next to his and saw Pokowski's personals lying there.

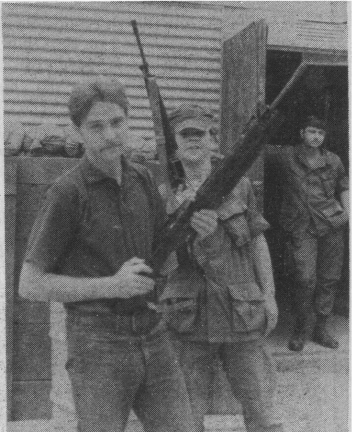

The two began touring with a Special Services band and after eight months of waiting was finally given permission to join Special Services. Luckily, he was placed with some other soldiers who shared his musical interests and they hit the road in Vietnam as Captain Zig Zag's Blues Band.

"All of a sudden my tour of duty in Vietnam was areal adventure," said Marlatt. "We would just go out on the road with our instruments and our weapons. We'd come into an airport where a smoldering C-130 was just being pushed off to the side after being shot down. We'd get ambushed on the way to gigs. I've got stories that are crazier than Apocalypse Now.

Marlatt and his comrades were musical mercenaries: "I had a bandoleer of grenades across my chest and a guitar slung over my back."

Marlatt even won a Silver Commendation for his role in wiping out an enemy machine gun nest. The band was on its way to a gig when it happened.

Eventually, he was reassigned to an infantry unit outside Bien Hoa and in February, 1972, Marlatt used the G.I. Bill to go to Berklee College of Music in Boston to learn all the tricks of the trade. After undergoing a preliminary training session, however, he hooked up with a Lexington band called the Hatfield Clan (whose members later formed the Metropolitan Blues All-Stars).

The band toured the south during the southern rock craze, opening for the Charlie Daniels Band, the Allman Brothers, Elvin Bishop, Lynyrd Skynyrd and Bruce Springsteen.

After about three years of playing everything from Muddy Waters covers to jazz and fusion —but no southern rock, so as to keep a unique sound — Marlatt decided it was time to go to school.

He graduated with degrees in music arrangement and composition, as well as audio engineering. He also studied film scoring. While at Berklee, he met many soon-to-be-famous musicians and watched fledgling bands such as Journey, Boston and the Talking Heads when they were playing the Boston bar scene. Marlatt lived, studied and worked there for eight years before leaving.

While he wanted to go to either Los Angeles of New York, it posed too great a risk at that time. "Those are two tough cities to just move to without knowing someone or having a gig."

So, it was back to Louisville in 1982 to build up contacts and credentials and prepare for the journey to the big city. He joined a band called Crisis, playing jazz, funk and R&B, but the band didn't stay together long. He then went to Crescent work at Crescent Recording Studios in engineering, but he couldn't quite make the same waves he did in Boston.

Before he knew it, he was accepting jobs waiting tables, painting houses or doing carpentry work. He was depressed, taking too much medication and very much alone.

"Everything I tried to do was a dead end," he said. Then came the fateful Fat Cat's incident. While he had been writing more complicated music, he returned to blues almost on a whim.

"No. 1, I just felt I needed to be doing something to help my depression," he said. "I picked the blues because I wanted to go back to my roots. I just wanted to look forward to Friday night where I could play in front of people."

Until that point, he had been known to all as John Marlatt. It was at the forming of Curtis and the Kicks that he switched to using his middle name. "I decided to switch to an alter-ego image. It was therapy. I noticed I was playing with so much more feeling and I think it was because of all the crap I'd been through."

In the mid-'80s, playing at Fat Cat's, Daddy's. the Rudyard Kipling and the like, the Kicks gained momentum, as did blues music in general. This was thanks in part to famed blues guitarist Stevie Ray Vaughan.

"People kept coming up to me and saying I sounded like Stevie Ray Vaughan. I thought, "Who in the heck is this guy?'

Then, while driving along one day in 1985, Marlatt heard David Bowie's "Let's Dance" on the radio. "I heard the solo and thought it was refreshing to hear."

The disc jockey then said the guitar work on the recording was done by Vaughan. "It hit me then," Marlatt said. "I went the next day and bought his album. I kind of had this soulful bond with him and I'd never even heard of him.

The band went through its dues-paying and many personnel changes. Officially, it is now a trio with Marlatt, bassist Mark Richardson and drummer Damell Douglas. He hopes to add horns and keyboards, when the right people come along.

In the meantime, the title track of Something's Wrong won a 1990 Louisville Area Songwriters Cooperative award and the band won an Indiana Blues Society competition, which helped to get the band some popularity in Indianapolis.

Marlatt also writes a regular column for the Louisville Blues News, titled "Hot Licks with Curtis of the Kicks." In addition, he is planning to write a book based on his experiences in Vietnam.

To top off everything, Marlatt recently celebrated his two-year wedding anniversary with wife J. Lynn, who is scheduled to give birth to their son on November 1. The boy will be named Remy Charles.

For a man whose life was ar oller coaster of wild prosperity and heartbreaking tragedy, it appears that the ride has finally steadied. The direction is clear. His new-found prosperity has also invoked one more personal epiphany.

"I realized that if I could go over to a war zone like Vietnam and make it, I could do anything," he said. "I took all that negative experience and channeled it in a positive direction.

"There was one really important lesson I learned in Vietnam and it didn't hit me until I came home, but I noticed that all of the friends I made that had stayed in bands did not change. They stagnated. I was the one that changed and grew and it was all the blood, sweat and tears."

As he likes to say, fate never deals you cards you can't use.

Fate dealt Vietnam and depression and intermittent failures which have affected Curtis Marlatt's soul, but they did so in a much different way than they would most. This is one man who never feels sorry for himself, even when he is singing the blues. His wife is a testimony to that fact.

"He is probably the most dedicated, soulful person I know," J. Lynn said. "He's very intense and it comes out in his nusic. I have a lot of admiration for him.

"This is a tough business to be in and he's at the point now where he's ready to take the step to the next level. It's hard to make that step. There's a lot of frustration at times, but for 25 years he has put his heart and soul into his music. Nothing would make me happier than to see him get the recognition he deserves."

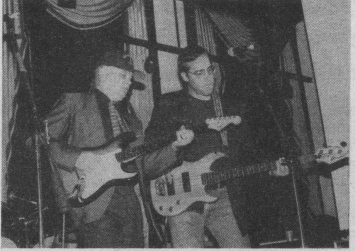

That kind of support has strengthened Curtis' resolve and he continues to play what he calls "Bourbon-Smooth Blues" — that's the blues, Kentucky style -— with triple the incentive.

"I'm making money, I'm playing the blues, I'm supporting a wife and son," he said, "and I'm back in the saddle.

"I've got my goals and I've probably had them in a way ever since the day I heard that Yardbirds song."

•

Curtis Marlatt will be appearing at Shenanigan's November 19-20 and at Da Blues club November 24-27.

Marlatt's album Something 's Wrong is available from ear X-tacy, Hawley-Cooke Booksellers and Electric Ladyland.