social bookmarking tools:

|

|

| Available RSS Feeds |

|---|

- Top Picks - Top Picks |

- Today's Music - Today's Music |

- Editor's Blog - Editor's Blog

|

- Articles - Articles

|

Add Louisville Music News' RSS Feed to Your Yahoo!

|

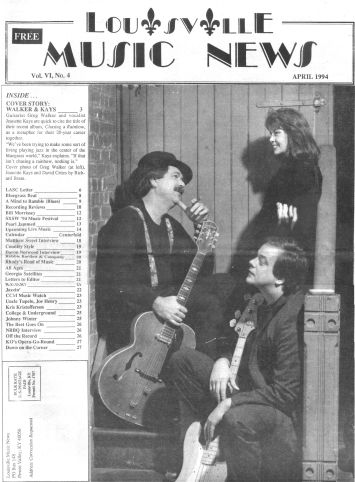

Walker & Kays

Guitarist Greg Walker and vocalist Jeanette Kays are quick to cite the title of their recent album, Chasing a Rainbow, as a metaphor for their 20-year career together.

"We've been trying to make some sort of living playing jazz in the center of the bluegrass world," Kays explains. "If that isn't chasing a rainbow, nothing is."

To which Walker adds, "Of course, the point is you can never catch a rainbow."

"But you keep trying," Kays says.

If life is a journey rather than a destination, then the musical trip Walker & Kays have been on for the past two decades has been a rich one. For whatever frustrations they may have encountered along the way in terms of recognition or financial rewards, they have achieved what many musicians seldom experience: artistic fulfillment and a sense of pride in their work.

"You might not love it every moment of every day," Kays admits. "But if you love it in the long run, you have to stay with it. So many people come up to us and say, 'I used to play music, and I wish I hadn't quit.'"

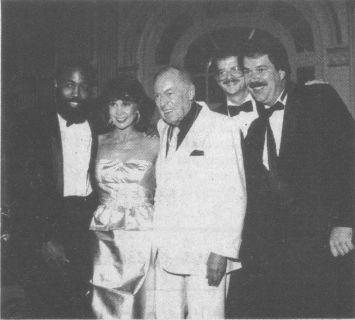

She admits that they have sometimes considered giving up, but there have been too many reasons not to, such as opening shows for artists like Dave Brubeck and Lionel Hampton before thousands of people or the thrill of going to Los Angeles to record Chasing A Rainbow. Mostly it's been the fans who come up and say, "We love what you do."

Indeed, it's hard not to like Walker & Kays, not only because of their talent but because they so obviously enjoy what they are doing and exude an upbeat, positive attitude. They can sound slick and playful simultaneously, lines blurring between what is rehearsed and what is improvised. Their songs speak of love won and love lost, and something in their voices tells you that they know whereof they speak. But even when singing the blues they rise above the sorrow and pain, as if drawing strength from the experience and looking towards a positive tomorrow.

They play off of each other perfectly, Walker's droll pragmatism contrasting with Kays' bubbly optimism. In conversation, Walker will serve as Kays' straight man, setting up her punch lines much the same way his guitar provides a cushion for her voice. But they'll suddenly reverse roles, and either of them at any time can be sentimentally tender, bitingly sarcastic or hilariously funny. Each knows what the other is going to say to the point that they often finish each other's sentences, and yet each is capable of catching the other completely off guard.

Musically they do the same thing, improvising freely and jumping off musical cliffs, secure in the knowledge that the other will follow and they'll both land safely.

Of course, in 20 years, their harmony has had its moments of dissonance.

"We've had some great arguments," Walker boasts.

"Remember the time I almost walked home from Lexington?" Kays chuckles.

"How about the time you wouldn't speak to me for several days?" Walker replies.

"You didn't deserve to be spoken to. You were being a stinker," Kays says, righteously.

"And what about the time I wasn't speaking to you? Get this," Walker says, laughing. "While we were on stage, I was communicating with Jeanette through our bass player, Sonny Stephens, even though I was in the middle and Jeanette could hear me just as well as Sonny could. I'd say, 'Tell the singer that the next song is such-and-such.'"

"And Sonny would do it!" Kays says, laughing to the point of tears.

So what were those arguments about?

"Let's just say that you've got two strong personalities who are both pretty opinionated about creative things," Kays replies. "In 20 years, you're not going to agree all the time."

Lord knows Walker is opinionated especially about himself. A common joke is that sometimes Greg doesn't like the way he plays, and the rest of the time he doesn't like the way his guitar sounds.

"I don't consider myself a great guitarist," he acknowledges. "When I hear someone like Jimmy Raney, it baffles me how well he plays. Around town, some people put me in a category with guys like Jack Brengle and Scott Henderson, but I genuinely don't think I play as well as those guys. I think I'm somewhat unique, though, and I can communicate with an audience pretty well."

Kays says that Walker's strength is his ability to convey emotion through his playing. "He is a very soulful player," she says. "You know how he feels the minute he puts his fingers on those strings. He does not play clinically, which means that he does make some mistakes, but it also means that what he plays is very much him, not just something that is written on a page or that was drilled into his head. It's very raw and very real.

"I listen to a lot of blues guitar players, and some of them are very good technically, but I don't particularly enjoy listening to them because everything is perfect. I want to hear what's coming out of that man's guts. If I can't hear a human being coming through, I may as well listen to a machine. When you hear Greg, you hear Greg whether you want to or not."

Walker admits that people sometimes have to tell him to lighten up. "On our album, I can tell you every mistake and every note that's out of place," he says. "The engineer finally told me, 'Look, this thing feels good and it sounds good. Don't pick it apart.' He wasn't hearing every nit-picky thing that was wrong, but I was, and it bugged me."

But Kays says there's a good side to Walker's perfectionism. "It makes you realistic about what you're doing and you work harder to be better. If you're happy to be mediocre and don't know the difference, that's as good as you're ever going to be."

Walker credits his individuality as a guitarist to his lack of formal instruction. "I had a 'black sheep' uncle who used to show up at our house on occasion, and he played country-western guitar," Walker recalls. "I had an old guitar that someone had given me and he taught me a couple of chords. I bought my first real guitar from Durlauf's when I was about 14. It was a blond Gibson 330 TD thinline, and I still have that guitar today."

Walker took a total of seven guitar lessons from a teacher at Durlauf's, and that was the end of his formal training. "But Ralph Lampton, who worked at Durlauf's, was a big influence on me. Even though he wasn't a guitar player, he would show me chords on the guitar that were more involved than the typical rock 'n' roll chords. Then there was a guitar teacher named Johnny Frisco who taught at Tunesmith in St. Matthews. I never studied with him, but I used to hang out with him and he would show me different fingerings."

Walker's first band was the Villagers, who played standards. He also played in a rehearsal big band that further exposed him to jazz harmony.

"Then I got the rock 'n' roll bug," Walker says. "My first group was called Froggie & the Gremlins. We never played a gig, but there were some pretty good players, most of whom became the Epics. Then I started a group called the Essentials. In those days, every neighborhood had a band, so everybody played and a lot of musicians were created in the '60s. Today, kids don't have that opportunity, and I don't know where they learn."

Other bands followed, including Brutus & the Traitors, who played for fashion shows at Stewart's for which they were paid in Stewart's gift certificates; the Centaurs, who played Whispering Hills 36 weeks in a row by winning the weekly battle of the bands; the Nightcrawlers, a pro group that did some recording; and a four-year stint with Cosmo & the Counts, where Walker replaced Wayne Young. "I learned more from Cosmo about stage presence than from anyone," Walker says. "He was the last of the great frontmen."

Even during his years in rock 'n' roll cover bands, Walker was never one for copying other guitarist's solos note-for-note. "It always felt foreign to me to play that way," he says. "So I always played my own solo. I might play the first bar and sort of allude to the guy's solo, but after that it was all mine.

"I had a number of influences, but I never tried to play like them. The first guitar player I remember hearing was Chet Atkins. Then I was very struck by the way Johnny Smith could play, and I had an album by Tony Motolla that I listened to a lot. I was very much in love with the Jazz Samba album with Stan Getz and Charlie Byrd, and an album by Howard Roberts called H.R. Is a Dirty Guitar Player, which was a funky, bluesy version of jazz. I played with a guy in Indianapolis who told me I sounded like George Benson, so I got one of his albums, which was before he was a big success, and it thrilled me. It was real bluesy jazz."

After playing in a group called Natural Gas for a couple of years, Walker and the group's bass player, Phil Hawkins, started a duo called Hawk & Walk, who landed a gig at Keith's Landing. "After a few weeks the owner suggested that we hire a female singer just for Saturday nights," Walker remembers. "I decided to call Jeanette, who I'd heard on a jingle that I had been called to overdub on."

Jeanette Kays had been singing almost all her life, and she can still tell you the first song she ever performed. "It was 'Dance With a Dolly With a Hole in Her Stocking,'" she says, proudly. "My father taught it to me when I was two years old and I sang it for my mother when she came home from work. He was real excited because he had finally figured out how to control his hyperactive kid through music."

Her father, Russell Burch, was a professional musician who played trumpet and guitar and worked six nights a week while also holding down a day job. "I remember as a very young child going to the places my dad played, and mother and I would watch from the side of the stage. One night I went up to the woman who sang with the band and told her that when I grew up I was going to have her job. They finally let me sing with the band when I was about five. I sang 'Temptation,' which was a ridiculous song for a five-year-old to do," Kays says, cracking up at the memory.

Even before she started school, Kays was entering talent contests, winning the regional contest to appear on the Horace Heidt radio show. It could have been her big break, but wasn't. "The next step was to compete in New York, but my mother was very pregnant with my brother, so I stayed in Louisville forever," Kays recalls.

During her elementary-school years, Jeanette took dance and gymnastics lessons, receiving vocal instruction from her father. "He would play trumpet scales and I would match the notes," she remembers. "If I was off key, it drove him nuts. 'You do it right or you don't do it.'"

Sort of like working with Greg?

"Exactly," Kays laughs. "Greg is my father substitute. But yeah, I remember daddy telling me that you should never copy other people, just do what you do."

Kays now passes that same advice on to others through the performance coaching she does with actress and singer Ann Hodapp. One of their clients was Heather Paige Folsom, who recently won the Miss Louisville title. "We don't teach people to sing," Kays says. "We fine-tune what they do on stage work on their mannerisms and stage presence, and try to find out what is best in a person's performance and make that shine. We tell the girls we work with, 'Take what you do and make it the best it can be.' Because if you copy, you can only be second best. But you can be the best you there is."

Kays finds it difficult to cite specific influences on her style. "There are so many," she says. "As a child I listened to a lot of show music. I love Brazilian music, and when I was a kid we would listen to Cuban music on my dad's short-wave radio. I also remember putting a portable radio under my pillow when I was supposed to be going to sleep and listening to the black stations that played jazz at night.

"I listened to everything. I was never a jazz snob particularly, and I don't know why I ended up doing jazz except that it's challenging and there's so much freedom to do it different ways. I listen to everybody but I try not to copy anybody else. I try to listen to what the guys are playing around me and just go with whatever they're saying to me."

Kays frequently appeared on local radio and TV shows, including "Stairway To the Stars" and "Hi-Varieties," and was a semi-finalist in the WHAS Crusade for Children Queen contest. "Those were wonderful experiences," she says. "I don't know why they don't have those shows or that contest anymore. It was wonderful training for people who wanted to be in the arts. There are very few training grounds available anymore, and that's a shame. Where do kids go to learn now? People in Louisville who want to do something have to leave town."

Besides the TV and radio shows, Jeanette would work with her father, who would play guitar behind her singing, doing variety shows at women's clubs and USO clubs. Kays had every intention of going to New York and being on stage, but got married at age 18 and had children. "I couldn't run off to New York and be a good mommy, and being a good mommy was very important to me. So I opted not to perform at all."

That didn't last.

"After a couple of years I went to my dad and said, 'I'll sing anyplace, anytime, with anybody. Do you know anyone who is looking for a singer?' He told me about a friend of his who had a dance band that worked Saturday nights. I started working with them and got back into the swing of things."

Kays worked with a succession of bands and also did some jingle singing, often working at King Sound Productions with former Oxfords leader Jay Petach, who later moved to Cincinnati. "Jingles are fun," she says. "They are a whole different ballgame. You have to be very disciplined, and discipline isn't high on the list for a lot of performers."

One night in 1974, Jeanette and her husband decided to go to Keith's Landing. "A friend of mine, Quentin Sharpenstein, had invited me out to hear him and another guitarist who were doing a guitar-duo thing. I didn't get out for a few weeks, and when my husband and I finally went there, Quentin was gone, and the other guitar player who was Greg was working with a bass player.

"We sat there and listened for a while, and I was just mesmerized. My husband turned to me and said, 'You'd give your eye teeth to work with that man, wouldn't you?' And I said, 'You know I would.'

"Several weeks later when Greg called and asked me to work, I was trying to act real nonchalant about it, but when he hung up I was dancing around the house, because I really wanted to work with him to hear what he could do. He asked if I would work with him just one Saturday night, not wanting to commit to anything because he didn't know what I could do on stage. So I went out there and sang, and he asked me if I was busy the next Saturday night. And it was, of course, a very good experience. He knew how to accompany a singer, play the right things, and be heard himself without getting in anybody else's way.

"There is a fine art to that, and Greg is a very good accompanist. I've worked with other people who are marvelous players, but don't know the subtleties of backing up someone else. That is very important, because front performers are very dependent on who's behind them. Being out front can be very easy, or it can be a struggle because the people who are supposed to be accompanying you aren't listening to you, or they don't care, or they don't know. It is a wonderful privilege to have someone who supports what you are trying to do. The players all know that it is a group effort, even if the audience doesn't."

One Saturday night, after Kays had worked with Walker and Hawkins a few weeks, Jeanette said that she wanted to try something with the tune "Lover Man," telling Greg, "I'm going to take some liberties. Whatever happens, just keep playing."

Walker was astounded at what he heard. "Up until that point we had been playing pretty wallpaper music," he says. "But when I heard what Jeanette could do with a song like 'Lover Man,' I knew we had been playing the wrong stuff.

"Jeanette has incredible ears," Walker says. "She's even better than most people give her credit for. Until you work with her you don't realize how improvisational she is, because she is so slick that it sounds rehearsed. But I can alter chords or change colors whenever I want and she's on it in a second. That's why it's so much fun for me to play with her.

"Besides being a great musician, Jeanette is genuinely one of the nicest, most thoughtful, most loving people I've ever met. And she's no ding-a-ling singer; she's smart and has a good business head."

While jazz ballads have formed the nucleus of their act ever since that night they first played "Lover Man," both say that it is wrong to think of Walker & Kays as strictly a jazz group. "Jazz is where our uniqueness is," says Walker, "but we can handle a lot of things. We've done country-style jingles together."

"If we are billed as jazz, we try to stay pretty close to that idiom," Kays says. "But otherwise, we try to mix it up. If you hired us for a corporate dance we'd mix in some '60s rock 'n' roll, standards, and heaven knows what else. There are many different sides to our performances these days."

One decidedly non-jazz attitude evident in the group is their willingness to reach out to the audience, a fact reflected by their usually formal stage attire. "The Modern Jazz Quartet always dressed up," Walker points out. "But most of the entertainment value of jazz is gone. The musicians figure that the music will carry it, but the audience isn't schooled, and that's one of the reasons jazz isn't as popular as it used to be. If jazz musicians were not so reluctant to think of themselves as entertainers, it would be more popular. But with some of the young players who sometimes work with us, it's hard to explain to them why they shouldn't wear a T-shirt with an advertisement on the front of it."

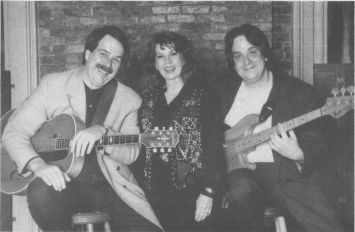

Another misconception about Walker & Kays is that the group only consists of Walker and Kays. They've always worked with a bass player, and for years the band's name reflected that fact. But after evolving from Walker, Hawkins & Kays through Walker, Stephens & Kays, Walker, Pietrus & Kays, and Walker, McCullouch & Kays, they decided to go for a more consistent identity by sticking with Walker & Kays.

But both are quick to credit the importance of David Crites, who has been in the band for the past six years the record for longevity.

"David is a very integral part of the group and a very good musician," Kays says, "and without him we would have a very different sound."

"David can play bass and sight-sing a written vocal part," Walker says with admiration. "Someone like that is very hard to find."

"He's also very tall," Kays adds, deadpan. "That's a big help when it comes to putting the P.A. speakers on the stands."

Kays says that working with Walker and Crites is a pleasure because both are aware of the nuances not just of her notes but of her lyrics as well. "The words are just as important to me," she says. "I don't sing tunes that are obscene. I have a couple that are cutely suggestive, maybe. But you will not find me singing lyrics that are blatantly sexual. I try to sing tunes that I wouldn't be afraid to sing in front of my mother. I also act them out a bit in the way I do them. That's the cabaret style, where you don't just sing the songs, you try to carry people with you."

However hard Walker might be on himself, he's proud of Walker & Kays as an entity. "I think we sound good most of the time, and we both genuinely like the music we play and understand what we're trying to accomplish."

Which is?

"The whole point of Walker & Kays is to take tunes that you would recognize and do something different with them," Walker replies. "I don't learn as much about musicians by hearing them play original tunes as I do from hearing how they change a tune that I know. That's why we like to play standards and alter them."

"I want the tunes to carry some kind of positive message," Kays adds. "I love beautiful ballads like 'You Must Believe in Spring' or 'Angel Eyes.' Anyone can get into those lyrics if they've lived life at all, and I like to carry all those wonderful messages of life."