social bookmarking tools:

|

|

| Available RSS Feeds |

|---|

- Top Picks - Top Picks |

- Today's Music - Today's Music |

- Editor's Blog - Editor's Blog

|

- Articles - Articles

|

Add Louisville Music News' RSS Feed to Your Yahoo!

|

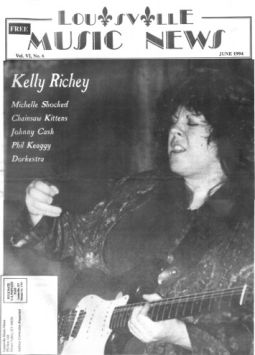

Kelly Richey

Soul-searching with the blues

By Jeff Walters

Kelly Richey remembers a time in the early '80s when she fronted a Christian rock band featuring a Jewish bass player. "It was the worst experience of my life, musically," she said. Contrary to what you might expect, the band's end was hastened not by issues of doctrine within the band but by religious intolerance of another kind: "I couldn't help anyone; I wasn't allowed. You really want to try to do something, and by the time you get through all the rules and regulations and judgments, there's no music."

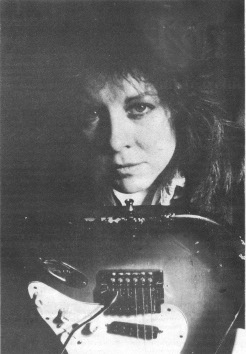

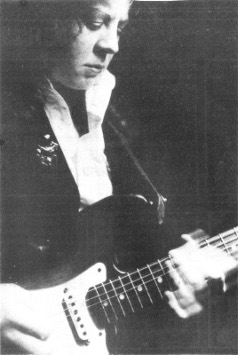

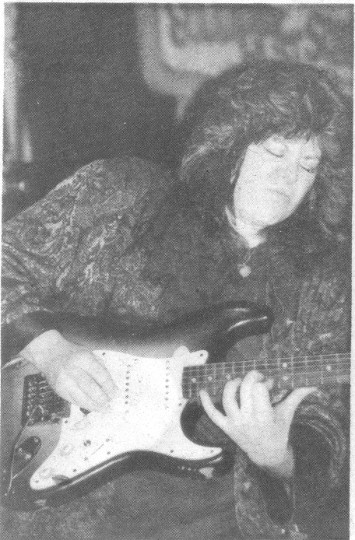

These days the fiery Lexington guitarist and singer, supported by drummer Shawn Wells and bassist Terry Williamson, is making her own rules and still confounding expectations, while playing a style of music that some people repute to be the handiwork of that "other" guy. (That's a charge that Richey will happily lay to rest for you, by the way.)

Richey's self-released new CD, Sister's Got a Problem, is a no-frills and no-nonsense statement of purpose that reflects her hard-earned "live" reputation. The band, which is playing regularly while fielding management offers, had its recent album release party recorded for broadcast later this year on National Public Radio's acclaimed "Bluestage" program. And Richey, who has sampled her share of the perils and pitfalls of the music business — and who has in fact come to terms with the oxymoronic nature of the term "music business" — is no longer intimidated by it.

"Everybody is going to make a fair share of mistakes," she said. "But I think if your head's on straight and your eyes are open, you can make the right decisions. Being sober the last few years has made all the difference in the world. Character judgment — you just don't make the same mistakes. I really have to attribute the roads I have gone down that have not been the right roads to being my own fault."

The roads that Richey has taken have passed over uneven terrain. There have been peaks, like playing at Farm Aid in 1990 with Stealin Horses, like jamming with Albert King and Lonnie Mack. There have been valleys, like being broke on the road with a band she wasn't even a full-fledged member of, like struggling with years of substance abuse.

Sitting in a pleasantly noisy coffee shop on a recent afternoon in Lexington, a clear-eyed Richey discussed her past, present and future. She told why she's happy with her current band. She talked about God and religion, art and commerce, words and music. She spoke softly about loud music. She addressed issues of gender and of color, of whites and blacks and blues.

Kelly Richey, like major influences Janis Joplin and Bonnie Raitt, is a white woman who has been touched by the non-discriminatory hand of the blues. Like Raitt, she plans to live in happy coexistence with them rather than die of them.

"The music that I'm playing is true to form. Even though it's more rock than it is blues, blues is the direction I'm headed in. I think I have a lot of blues in my playing, and it's a genre that I can grow old playing. I don't think I ever have to quit playing."

The blues had a baby . . .

Richey, 31, hasn't thought about quitting since her dad, without recognizing the ultimate significance of his action, bought her a Sears guitar and a three-watt amp when she was in 10th grade. A "long-haired boyfriend" had recently opened her eyes to real rock 'n' roll, a phenomenon previously unknown to her. She immediately started taking guitar lessons from a hard-living instructor whose belittling methods drove her to prove him wrong.

"I used to call him an old bluesman," Richey recalled with a laugh. "He wasn't much older than I am now. He was a real player, and he was a real hard liver. He didn't have much patience or tolerance. I don't know that I would have learned to play if I had taken from anybody else but him. He was mean, and he'd laugh at me and say girls didn't need to play guitar. He kept me so mad that I didn't set it down.

"I took it to school with me every day. I was totally taken with the guitar. And I have never set it down. Most musicians I know have had a few years off here and there; they've gotten in and out of it. I've done it every day of my life. That's all I know."

Her high school years were a period of anger and frustration for Richey, who is dyslexic. "I was an awful student. I made average, above-average grades at best. I had a good IQ, but there were performance problems. I was one of those people who fell through the cracks. I wasn't college material."

Words didn't come easy, but her instrument became a voice through which she could freely communicate. "Everything that I bring in is oral, audible. Music has always been something that I could do. That's probably the reason I express myself so much with music and not in other parts of my life."

In recent years Richey has worked to develop a voice as a songwriter. It hasn't been easy, but she's pleased with the progress. Six of the 11 tracks on Sister's Got a Problem are Richey compositions.

Despite her progress as a songwriter, she remains more comfortable letting her ax do the talking, in a voice that often invites comparisons to Hendrix and Stevie Ray Vaughan while also evoking lesser-known but equally important influences like the late Roy Buchanan.

"You can only talk about so many bad situations in the blues. There's only a few dozen kinds of bad days, bad relationships you can have. It can only get so bad and then get so much worse. It's really all how you feel it, and how you put it out there. The guitar just seems to say so much more to me than just a bunch of words.

"Now, if I could write like somebody like Don Henley, and really talk about life, I probably wouldn't be doing blues. I'd probably be doing pop music. I think that's the difference. I've never heard a blues song that lyrically changed my life and heightened my awareness — but I sure have had it heighten the awareness of my soul."

Down to the Crossroads

Matters of the soul have always held a prominent place in Richey's life. Raised in a Southern Baptist family, she was sheltered from the worldly influence of rock 'n' roll, but she received an early introduction to black culture. At a young age, Richey experienced soul.

"My uncle was a preacher here in town, and we had the first church to integrate," she said. "It was burned to the ground when I was almost 6. A man named Dr. J. Robert Bradley, who was friends with Mahalia Jackson, would come to our church and hold a revival every year. And he'd sing black gospel music.

"He was as wide as he was tall, and he was as black as black can be. I adored him. He and I got to be really close friends, and he gave me my first charm bracelet. To a kid, stuff like that is a big deal.

"When he held revivals, a lot of the black community would come to our church. And I saw: They've got something going on that we don't. It planted a seed, which I was able to reconnect with when I started getting back into blues. I started realizing its roots in black gospel, and I have spent the last five or six years really immersed in black roots music."

Therefore, when Richey speaks of vocal influences, she quickly lists, along with obvious choices like Joplin and Raitt, the gospel great Mahalia Jackson, who was herself heavily influenced by the blues.

"I love her," Richey said, before adding with a sheepish laugh: "I wish I wasn't white! I mean, I do."

Of course, despite the musical relationship between gospel and blues, the two forms are often considered to be polar opposites, spiritually speaking. Richey fully realizes this, and she has confronted the issue head-on.

As a teen-ager in church, "I was dragged to those things where they turn the music around backwards," she said. "I guess what I do would bother a lot of people. But I'm on a first-name basis with God, and I talk to him every day. And I'm alive and healthy because of that relationship."

Her relationship with God has sustained her, she says, through the difficult times and the temptations that so often accompany the musical life. Organized religion, however, is another story.

"I don't think religion has anything to do with God," she said. "It's people's view of God. I'm more interested in God's view of people, and just the basic principles that don't fail if you live by them. It's not rules and laws and that kind of stuff that people have turned it into. It's the principle, and this world lacks principle. . . . The arts, I think, really need to do something. People need to stand for something."

Racial problems are a serious issue for Richey, who wrestles with how to get involved by setting a positive example rather than by starting a fight. "You can't change the world," she said. "You know, me being white, so what? Color is not the issue. Lack of understanding and honesty is the problem. . . . A lot of people talk about wanting to see change, but when it comes down to those people who really want to get out and do the work, the numbers dwindle very quickly."

She acknowledges that, even today, the band plays in places where it could not if it had a black member. "What do I do about that? Do I not play in those places anymore? You don't make change by walking away and being mad. You realize that people don't know any better. People are raised to believe what they believe, and the best we can do is live our lives and hopefully set a new example. And you have to go into those places."

"City Between the Lines," an original song from the new album, tackles the issues of prejudice and inner-city violence. Richey doesn't spare herself in the song, which she began writing in response to the Los Angeles riots that followed the Rodney King trial.

The song opens to the sound of a siren, which yields to a sparse but insistent rhythm over which Richey sings lines such as: "I see your city burning / It's not mine," and "We run from each other / and take sides."

Although the song definitely has a bluesy feel, it's not a traditional blues. Like the best blues, however, it is painfully honest — and it doesn't supply any easy answers, because there aren't any.

'Shut up and write'

"City Between the Lines" was started when the riots broke out, but the song wasn't completed until after Richey had forged a relationship with an old acquaintance she met while performing for a local writers group. The new friendship proved to be an inspiration for her songwriting in general.

"In the last two years I have become friends with a black woman I went to high school with. Her name's Donna Johnson," Richey said. "I played for Working Class Kitchen, and Donna was there. I looked at her, and she looked at me. We knew each other from high school, but we hadn't been good friends at all; we hardly knew each other.

"I went to her and said, 'Look, you're a really good writer. I'm really into black roots, doing a lot of blues. Will you write with me?' She looked at me real long and hard and said . . . 'Yeah.'

"She came over to my house a few times, and she really talked to me. She helped me a lot. Basically she said, 'Kelly, honey, anybody who talks as much as you do needs to shut up and write.' Within three months I had material for the record."

Johnson, a poet, writer and teacher, was also the inspiration for the album's title track, according to Richey. "I wrote "Sister's Got a Problem" because of a phone call I received from her one day. She wasn't having a good day. And I wasn't able to finish 'City Between the Lines' until after I'd been around Donna for a little while."

Richey added: "One of the things that Donna and I have done a lot with is the fact that we are all prejudiced. And what are our prejudices? What did she think about me; what did I think about her in high school? We've been real honest with each other, and it's been a tremendous growing process for me."

You can't judge a book . . .

Throughout the numerous configurations of bands that Richey has played in over the years, there have been a couple of constants. One is a reputation for passionate, incendiary live performances. Another is Richey's ability to take even the most well-worn AOR standards and make them her own.

"Classic rock" staples by the likes of Zeppelin, Bad Company, Hendrix, Clapton and Joplin become fresh and exciting in the hands of Richey and company, while the songs of Robert Johnson, Little Walter Jacobs and more recent counterparts like Albert Collins let the band further explore its blues muse.

On the album, the band gives the Richey treatment to three blues chestnuts: Johnson's "Ramblin' on My Mind"; Jacobs' "Mean Old World," which Clapton covered during his Derek and the Dominos days; and "Serves Me Right to Suffer," which is reworked as "Serves You Right to Suffer." From the rock side, Kelly contributes a stunning version of Neil Young's "Down by the River" and a Hendrix-style cover of Dylan's "All Along the Watchtower," recorded live.

"I tried to pick the songs from our set list that were most well received and that balanced out the record," Richey explained. "A lot of the stuff that I wrote is more of the rock/funky-type blues. There's one real traditional blues song that I wrote on there, "The Blues Don't Lie." But "Sister's Got a Problem" and "City Between the Lines" aren't what you'd call traditional blues songs by any stretch of the imagination. "Travelin'" is a real three-chord blues-rock or rock-blues kind of song. "I Don't Feel So Good" is funk-oriented.

"I tried to pick songs that would balance out the record, because as I grow I want to move more and more into the blues."

Richey's philosophy on performing cover versions is simultaneously modest and confident.

"I think rock 'n' roll, which is very blues in its origin, is a bunch of three-chord songs. There's not a lot to it. I think the essence of what rock 'n' roll means is that it's your own interpretation. A place where you can stand and do what it is that you do. There isn't a single song we do that we haven't made our own."

Because of the obvious influence Stevie Ray Vaughan has had on Richey's guitar style, many people think the band performs Vaughan's material. But that isn't the case, as the guitarist points out with amusement.

"We don't do a single Stevie Ray Vaughan tune, and I don't know that we ever will. I'm totally influenced by him, but there's not a song of his that I've ever tried to play, in the privacy of my own rehearsal, to where I felt like justice was done. And I'm not going to do a song just because people think we should do Stevie Ray.

"People bug me to death about Stevie Ray; why don't I do Stevie Ray; I ought to do Stevie Ray; I'm lying to them, I really do." She laughed at this last comment, before adding, "It just doesn't feel right."

Playing with her friends

One thing that does feel right to Richey is the current lineup of her band. Wells, the drummer, is a 22-year-old who has been playing with her for a year and a half. Williamson, the bassist and the most experienced band member, is in his mid-30s and has been in the band for about a year. Among other contributions, Wells brings a sense of youthful enthusiasm to the proceedings while Williamson provides stability and someone to bounce ideas off of.

"The band has evolved tremendously," Richey said. "For the first time I've experienced having a group that is starting to make its own sound. It's not just my guitar playing and these guys following me. It's really three people."

With all three musicians staying clean and sober, Richey has found a strong support system that she thinks and hopes will remain intact for the long haul. If things go as planned, the band could start making noise outside its regional base. But first things first.

"Before we can go any further, we need management," Richey said. "Right now I'm wearing too many hats. It's a full-time job, booking a band, keeping up with the publicity and all that goes with it. We've got about 500 people on our mailing list. . . .

"It's time for me to go back to playing the guitar and try to find somebody to handle these business aspects. I think I have a decent business head on my shoulders, but I'm a guitar player."

Having witnessed firsthand the sometimes unsavory business side of music, Richey remains determined to succeed in the industry by making wise decisions.

"One of the biggest choices I'm going to have to make," she said, "is finding the right producer. I've become friends in the last eight months with Lonnie Mack. He coached me through this record, gave me a lot of advice, listened to my material. This being a self-produced record that we just put out, I see that it's not that commercial, that marketable and mainstream. . . .

"Hopefully, when your focus is really at its finest, you can find that right producer who can understand and help you interpret your music in a way that can commercially be marketed."

She doesn't worry about falling prey to over-production.

"I have never had anybody try to make me slick," she said. "I'm not sure that you could. If anything, I would love to mature and be able to polish the edges. Not in a slick way, but just kind of polished. It's pretty raw and in-your-face music, and some people like that. If some of the edges were polished and my vocals were developed more, maybe even a keyboard added sometime in the future, I think that would make us a lot more dimensional. And I would enjoy it.

"I look at Clapton when he was with Cream, and I feel like that's kind of the phase we're in, that three-piece rock and blues. I'd really like to see us develop as far as we could."

The band has received invaluable help along the way from Duane Adams, who engineered the CD at his fledgling Legend Sound Studio in Cincinnati, and WUKY's David Farmer, who recorded the release-party concert for "Bluestage."

"They have really helped make all this possible," Richey said. "And I think it will be a good springboard to take us places.

"Everything feels right. It feels like it's right where it needs to be. And it's right at a pace that keeps us honest, which I think is real important."

Yes, Kelly Richey's got the blues. And it feels righteous.