social bookmarking tools:

|

|

| Available RSS Feeds |

|---|

- Top Picks - Top Picks |

- Today's Music - Today's Music |

- Editor's Blog - Editor's Blog

|

- Articles - Articles

|

Add Louisville Music News' RSS Feed to Your Yahoo!

|

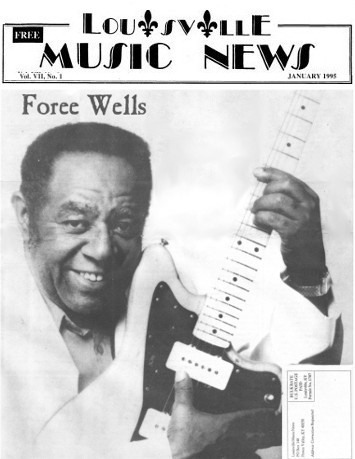

Foree Wells

By Mark Clark

The setting was rural Arkansas, circa 1955. Force Wells Jr. was playing guitar in a hole-in-the-wall blues club alongside bandmates Earl Forrest and Bill Harvey when a fellow walked in carrying a ratty old Gibson hollow-body.

"I think we had played three numbers and this guy walked in. This guy says,. 'Can I sit in?' I says,'Yeah.'... When he got up there and started playing, I couldn't believe it. I tried everything I could on that old man. He made me feel so bad. We did two more numbers with him. He just looked at me and laughed, smiled all the time. Earl Forrest was over there cracking up. That was the first time a guitar player had wiped me. He knocked me out ... I told him, 'I was trying to wipe you out and you kicked my butt like it wasn't nothing.' He just laughed about it."

Wells didn't find out until the set was over that "this guy" was blues legend Albert King. "I didn't know who Albert King was. That old guy could play."

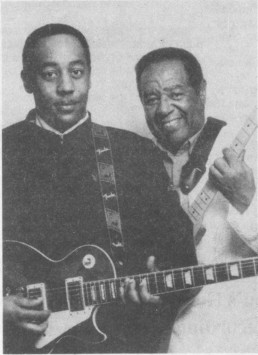

Nobody had blown Wells off the stage before King and few have done so since. In his long career in music, which dates back to the early '50s, Wells has played with some of the best in the business. But nowadays he's playing with a group he enjoys even more — his own children. Wells fronts the Walnut Street Blues Band, which also includes his three sons, Foree III, 36, Gregory, 35 and Michael, 33.

The group recently finished recording its first album, which is slated for early 1995 release by Rooster Records.

"I went to Memphis to play one gig."

Wells, 58, grew up in West Louisville, where at age 9 he took up playing the guitar, picking out the country standards his dad listened to. At age ll, he formed his own band —The Alvin Thomas Band, featuring Wells, Thomas and three elementary school classmates.

He didn't begin pursuing music seriously until 1953 when, at age 17, he joined the Morgan Brothers Band. And even then, he wasn't interested in playing blues, even though he stayed up late to listen to blues on the Midnight Sun program on WGRC Radio (now WAKY) from l0 p.m. to midnight. He was entranced by B. B. King, but couldn't seem to master the blues himself until, through the Morgan Brothers band, he met guitarist Edgar Porter, who went on to join Hank Ballard and the Midnighters.

"I heard blues and tried to play it, but couldn't do anything much with it," Wells said. Then Porter agreed to show him some blues chops. "Edgar Porter was the one who got me involved (in blues). He was my biggest inspiration because he could do everything B. B. could do and I wound up playing more than he did."

Wells' big break came one night when the Morgan Brothers were playing in Nashville. After the show, he was approached by a producer from Memphis, who invited him to sit in with the Bill Harvey Band, who had just been fired by B. B. King and had been hired as the house band at a Beale Street nightclub. The producer was looking for someone who could play B. B.'s parts and Wells, strongly influenced by King, proved to be a perfect fit.

"I went to Memphis to play one gig," Wells said. He wound up staying about three years, working as a session player at every studio in town, including the famous Sun Studio. He played alongside Bobby Bland, Roscoe Gordon and the Kid King Combo and met the likes of Elvis Presley, Carl Perkins and Howlin' Wolf. But his biggest thrill came one night when he was playing with Bill Harvey. In the middle of the set, Wells' biggest inspiration, B.B. King himself, walked in.

Wells was in the middle of a B. B. King song. For a few seconds, Wells stopped playing, dead in his tracks.

"It shook me up," Wells admits.

But after the set was over, B.B. shook Wells' hand and said to Harvey: "He's all right."

Not all Wells' experiences in Memphis were magical. It was there that he first saw how heavy drug use can destroy lives.

"This guy would be playing and all of a sudden he would just stop, " Wells said. "I'd ask, 'What's with him?' They'd say, 'Junior, we'll tell you about it.'" It tums out the saxophone player was addicted to heroin and stopped in mid-song to go shoot up. Later, older musicians warned Wells, "'Don't do what we do. Do what we tell you.' They scared me to death. They put fear in me and it's still in me. I never tried it. You'd see guys going crazy, guys getting letters from their wives, getting divorced, getting sued for non-support and it wasn't because these guys didn't love their families. They didn't have nothing to send back because they used it all on drugs. A wise man looks and listens and I was always watching everything.

"You don't use drugs in my band. If you do, good-bye. No ifs and ands or buts about it."

I've never been so embarrassed in all my life."

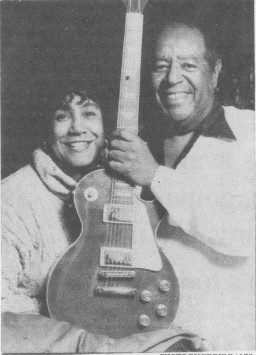

Eventually, Wells tired of the grueling pace of work in Memphis and grew homesick for Louisville. He returned here in 1956 — which proved to be a pivotal year for Wells. He met and married his wife, Lorene; he landed a day job with L & N Railroad, where he was employed until February 1994; and he formed his first band, the Foree Wells Combo.

Later, he disbanded the Combo and formed the Rockin' Red Coats. You guessed it: Everybody wore red coats. In 1960, dissatisfied with the performance of his keyboard player, Wells decided to buy himself a Hammond spinet. He quickly mastered the instrument and kicked out his unruly keyboardist — who refused to play on some numbers. While filling in for his keyboardist, Wells discovered he could make extra money with lucrative solo gigs on the side. Eventually, he gave up playing guitar altogether.

Meanwhile, he was raising his three sons -— and music was a big part of his childrearing strategy. He bought his oldest son, Foree III, a drum kit for his fifth birthday. Force III is now the drummer for the Walnut Street Blues Band. He bought guitars, saxophones and other instruments for his other sons. He figured if he could keep them interested in music, he could keep them out of trouble.

"It kept them home," he said."They didn't run the streets. That made a big difference."

It was a lesson Wells learned from his own childhood. Wells was raised by his grandmother in a household filled with 25 children, brothers, sisters and cousins.

"Only five of us never got in trouble," Wells said. "The five of us, I was playing guitar and the other four were singing. All we did was practice ... That kept us all together and the five of us never got locked up, never got in any trouble. The rest of the guys were always in trouble."

Eventually, Wells decided to break up the Red Coats and concentrate on solo keyboard gigs. For five and a half years. he played two sets per night, one set on Sunday, up to seven days per week at Holiday Inns, playing "cocktail music."

He was still working days at L & N. Finally, he had had enough and dropped out of music altogether for about four years.

In 1984, local bluesman Winston Hardy coaxed Wells into sitting in on his show at Tewligans (now Cherokee Blues Club). Wells was playing keyboards, as usual, when ~— as Wells tells it —Hardy told the crowd: "Everybody knows Foree. But he's not an organ player, he's a guitar player. I want to hear him on guitar. I said 'Man, I can't play no guitar. ' I picked it up and tried to, but my fingers were soft and everything. I've never been so embarrassed in all my life ... When I got home, I stayed up all night practicing. If it wasn't for Winston, I wouldn't be on guitar."

Wells says he feels he is "back at home" on guitar. "Guitar is not like organ. Organ's like taking candy from a baby. On organ, you can close your eyes and play all night. And you're sitting down. The guitar is a challenge."

Returning to his favorite instrument rekindled Wells' interest in music. Hardy "got me back into music. I got burned out when I was playing at Holiday Inn every night."

Wells left Hardy's band in 1988.

'"If I don't make it, I don't make it. At least I tried."

Wells' return to music proved to be well-timed.

He talked his sons, who had been playing together under the name the Jam Conductors (a tribute to their dad's L & N connection), into joining him in forming the Walnut Street Blues Band. The group quickly began getting gigs. Meanwhile, L & N changed his work schedule. Instead of the flexible hours he had been working, Wells was suddenly stuck working second shift, off Wednesday and Thursday nights.

"I hated that," Wells said. "When I turned into the property, I turned hateful right then and there."

So he decided to quit his job at L & N. After working there 381/2 years, he had earned a full pension. Now, for the first time since he was in his teens, he's a full-time musician – and, for the first time ever, he is leading his own band.

"I've been wanting to do this ever since I've been playing," he said."If I don't make it, I just don't make it. At least I tried."

Wells is hoping that the band's as-yet untitled debut album will be the first step toward success. He said he was happy with the recording sessions. "I thought the sessions went pretty good," he said. "You always think it could have been better."

The record will include 12 original compositions, mostly high-energy rocking blues tunes. If Wells' lyrics are sometimes simplistic, they are always heartfelt. Wells keeps his songs-in-progress in a tattered old Trapper Keeper. His favorite place to write music is in his van. "I don't know what it is, but I can write songs all day long when I'm driving. It just comes to me," he said.

The chief delight of the Walnut Street Blues Band's recordings is the interplay between Wells and his son Michael, who alternate on lead guitar. Wells offers oldschool B. B. King-influenced chops, while Michael serves up wild, rock-style licks, inspired by his idol, Jimi Hendrix.

Wells says what makes the Walnut Street Blues Band special is the unique chemistry between himself and his sons. Since the family has been playing together since the kids picked up instruments 30 years ago, they share a sort of musical ESP. Two of the best tracks on the band's forthcoming album – "Hey Little Blue Bird" and "Midnight is Falling" – were ad-libbed in the studio, with lyrics added later.

"The thing about it is, if I fall down somewhere they can pick me up. If they fall down, I can pick them up because we all know what we're doing," Wells said.

He hopes that this new band will be a legacy he can pass on to his children. "I want to make a success out of what we're doing and leave something for the kids," he said.

The question Wells ponders nowadays is, will anyone be listening by the time he turns the Walnut Street Blues Band over to his kids? He said many young blacks reject the blues, dismissing it as "old slave-time mus1c."

"They say,'That ain't nothing but three chords,' that kind of stuff. Blacks don't understand blues. I don't mean the people that made it, I mean the younger generation ... What broke blues open was all these boys from England, Eric Clapton and what's his name, that crazy sumbuck, Mick Jagger, and all that bunch. They broke blues open.

When the English rockers started doing it, well look at all the blues clubs in Louisville now. There weren't any before then. There might have been one."

He foresees more hard times for blues ahead, since the genre gets little radio airplay.

"Look at radio stations here in Louisville. Who plays blues, except for Scott Mullins from 10 o'clock to midnight? Nobody," Wells said. "That's all over the country, unless you go someplace like Chicago or Memphis."

So why does Wells love the blues? He says initially, he was drawn to the genre because it was something different, something he hadn't played. But he has stayed interested in it because of the lyrics.

"You ever sit down and listen to blues?" he said. "I mean, listen to the melody lines and things to it. Most blues tells a story about something happening ... It tells a story, it has a start and an ending every time."

Let' s end this story back where we started. Was Albert King the best player Wells ever performed with? Nope, Wells said, that honor belongs to Clarence "Gatemouth" Brown.

"He's very sincere about the way he plays," Wells said. "There's a lot of good ones out there who can't do what he can. Gatemouth can walk all over any guitar player, as far as speed or anything else. Of course, B. B. King's always been my favorite, but what's B. B. doing now? He's sitting down now. He's paid his dues. Gatemouth doesn't play like he's paid his dues, he's still trying to get his dues. I like to play with a punch and that's the way that guy plays."