social bookmarking tools:

|

|

| Available RSS Feeds |

|---|

- Top Picks - Top Picks |

- Today's Music - Today's Music |

- Editor's Blog - Editor's Blog

|

- Articles - Articles

|

Add Louisville Music News' RSS Feed to Your Yahoo!

|

Jazz Educators Roundtable

On a day in 1967, Jamey Aebersold took a copy of his very first jazz improvisation play-along record to a branch post office in New Albany, Indiana to mail it to a teacher who had ordered it. He handed it to the woman behind the counter, who looked at the label and then shoved it back at him.

"I can't take this," she said.

"Why not?" Aebersold said, thinking perhaps he had packaged it incorrectly for mailing.

"This is jazz," she replied.

"What do you mean?" Aebersold asked, incredulously.

"This is jazz," she repeated, her tone of voice leaving no doubt that she considered jazz on a level with pornography.

"This is music education material," Aebersold protested, but she would not be swayed. Finally, Aebersold asked to see the manager, who accepted his package without comment.

"It was the mentality of the times," Aebersold says today. "Jazz was evil music."

Indeed, the very name "jazz" was originally a euphemism for sex (as was "rock 'n' roll"). It was the music played in the brothels – "jass houses" – of New Orleans. And even after the genesis of the name had been long forgotten, jazz was the music associated with gangster and porno movies, and the musicians were considered bums and drug addicts.

Jazz had something else in common with sex: you didn't learn about it in school; you got your information on the street. Most college music professors had no respect whatsoever for improvised music, contending that the only valid music was that which had been written down by established composers. The ones who did respect improvisation, or at least recognize that certain situations required one to be able to do it, often felt that improvisation could not be taught. Either you were born with the gift of self-expression or you weren't.

Things have changed dramatically in the succeeding years to the point that jazz courses are offered on many college and university campuses, including the University of Louisville and Bellarmine College, and jazz instruction is also available with private teachers through local music stores.

But while jazz may no longer be equated with sin and crime, the music and the musicians who play and teach it are still viewed with a certain amount of suspicion by some members of the music establishment. To find out the state of jazz education in the Louisville area, Louisville Music News invited several local jazz educators to participate in a roundtable discussion. The participants were:

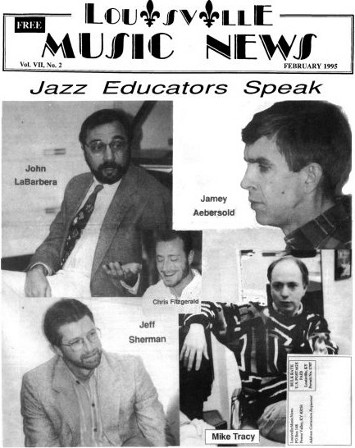

Jamey Aebersold: saxophonist. Teaches improvisation class at U of L. Nationally known jazz educator who has produced 64 play-along book-and-record sets and directs Summer Jazz Workshops. Aebersold was awarded an honorary Doctorate of Music by Indiana University and is a member of the International Association of Jazz Educators Hall of Fame.

Chris Fitzgerald: pianist, guitarist, bassist. Teaches guitar, bass and piano at Gittli Music Studios, and teaches piano, bass and leads the Louisville Jazz Workshop and other combos through the U of L prep department.

John La Barbera: arranger, composer, trumpet player. Teaches arranging and Music Industry courses at U of L. Nationally known composer/arranger whose works have been recorded and performed by Buddy Rich, Woody Herman, Glenn Miller, Count Basie, Doc Severinsen and Phil Woods.

Jeff Sherman: guitarist. Director of Jazz Studies at Bellarmine. Teaches jazz and classical guitar, electric bass and coaches ensembles. Also teaches at his own studio.

Mike Tracy: saxophonist. Director of Jazz Studies at U of L. Teaches saxophone, jazz theory and coaches ensembles. Former jazz teacher at Bellarmine.

RM: Judging by Todd Hildreth's monthly "Jazzin'" column in LMN, trying to be a jazz musician in Louisville would appear to be a pretty frustrating endeavor. So why would you want to teach students to be jazz musicians if all they have to look forward to is people asking them to play stupid pop songs at wedding receptions?

Sherman: It's the best education for anyone who wants to go out and make a living in music. You learn to improvise, to read, to have technical mastery of your instrument, to follow a conductor, to do everything that's required in music.

La Barbera: We are not trying to turn out jazz musicians; we are just one part of the music-education process. We have a jazz program here because it makes a more complete player. The jazz musicians we do turn out will probably not stay in Louisville but will go elsewhere to pursue jazz careers. Those who do stay in Louisville will know that they have to play other kinds of music, and they will be well equipped to do that. You're not going to make a living here playing just jazz, I'm sure, just like in any city this size. In fact, there is more jazz in Louisville than I've found in a lot of cities, and I've been around.

Tracy: I read Todd's articles every month, and he has a right to his opinion. Sometimes I can really relate to what he's talking about because I've been through those situations, but I don't always agree with what he says or how it's said. I play a lot in town, and Chris and I play together frequently. We have to do some of those same jobs that are not enjoyable in the sense that the music is not challenging. But part of the problem with life in general is that sometimes you have to do things you don't want to do. When I'm playing those jobs, I'm thinking about what I can learn that will help me do something else. In addition to that, the money I make on that one evening allows me to stay home the next few days and practice doing what I really want to do. When those jazz jobs come along where no one questions what I'm doing and lets me be myself, then it's like nirvana. And I've played "Giant Steps" at wedding receptions. I'm always careful to gauge the crowd, but I've never had anyone come up and say, "What do you think you're doing?"

Fitzgerald: You realize that they're not listening all at so you can do whatever you want. [laughter] The band has a great time and gets paid and nobody knows the difference.

You don't play this music thinking that you're going to make a lot of money at it or that people are going to love you for playing jazz. All you have to do is look at this industry to realize that jazz is not hugely popular. But if you love being a musician and you're working and eating and paying your bills, you can't really ask for much more than that. I think being a jazz musician in Louisville is pretty great just because of the attitude of the people in town. Yeah, we have to play pop music sometimes and I have to teach everything from Bach to Beck, but that gives me the freedom on my own time to do what I want to do, which is to play this kind of music and learn more about it. If you ask for more than that, you're probably expecting too much.

Sherman: Jimmy Raney told me that when he lived in New York he only played jazz an average of two weeks a year. The rest of the time he was doing other things. So there's one of the world's greatest jazz guitar players, and he didn't play that much jazz in New York. To play as much jazz as we have in Louisville is really a blessing.

RM: To get a perspective on how far things have come in terms of jazz education, I'd be interested in hearing some of the obstacles that you guys encountered when you wanted to study jazz.

Aebersold: When I applied to the Manhattan School of Music in 1957 they answered with a one-sentence letter: We do not offer saxophone. So I went to IU and they said they didn't offer saxophone either. I was already there! They said they'd put me on a woodwind degree where I would learn oboe, bassoon, flute and clarinet, and they'd let me take saxophone lessons from the clarinet teacher.

La Barbera: When I was in college in '63 and '64, we were not allowed to rehearse jazz anywhere on campus. We had to go to the basement of the public library.

Tracy: When I went to UK my first year of college, they had a jazz band, but only juniors and seniors could play in it. So I wanted to come back home and they said Jamey was going to teach saxophone at U of L. But when I played my first convocation–the weekly student recital–at U of L, I came out on stage and several faculty members got up and walked out. When I got done, they came back in. They didn't want saxophone at the school.

Sherman: Jamey, I remember you coming on a gig one night and saying that the U of L faculty said that you could teach saxophone technique but no jazz.

Aebersold: That's when I quit. I remember talking to [former dean] Jerry Ball at the time. I said, "Let me teach the classical literature plus how to make a living playing jazz and pop music." But they only wanted legitimate saxophone taught. So I decided that I had to leave.

Tracy: I'm now doing basically what Jamey offered to do back then. Some of the students really do want to play, for lack of a better term, "legitimate" classical saxophone, and I encourage them to also do other forms of music. There are others who only want to do jazz, and I need to help them do classical music so they can have a little more of a balance in their education. Basically, we just try to get them to be the best saxophone players they can be. I find playing transcriptions by Charlie Parker to be just as valuable as playing a piece by Paul Creston.

I'm giving a classical recital in two weeks. Most of the music I'm doing is new music written in the last three to five years, and most of it uses the same jazz techniques I learned from Jamey. It's not the same as swinging like Charlie Parker, but it's not like playing a Mozart piece either.

Aebersold: There was an article in a recent issue of Band Director's Guide by Don Sinta, who is one of the few recognized classical saxophonists in the world. He spent '94 on a sabbatical, and he spent much of the time learning to play jazz. The thing that stands out in my mind is that he said for all the technical skill he had, he didn't know what to play if there weren't any notes written out that he could read. I was thinking how tragic that is for a 56-year-old professional musician to not be able to create something from within himself, but how can you expect him to if his whole life has been reading notes off a page?

Tracy: Our dean, Herbert Koerselman, wrote in the alumni newsletter that he wished he could improvise in a manner that would be strong musically. He thought everybody should be able to do it and he would encourage that. That created quite a few raised eyebrows.

La Barbera: He sees the future, because students who will not be able to improvise will be unemployed, as professional musicians.

Aebersold: Also, there are teachers who realize they are not getting through to the students because they don't know how to teach improvisation.

RM: Gary Burton once told me that he thinks the reason so many people are afraid to improvise is because of the way music is traditionally taught, where teachers instill a fear of playing a wrong note.

Fitzgerald: Jazz can't be taught in the same way classical music is taught. A teacher can't just sit there and say, "No, E-flat." You have to give people so much space and try to help them get out of it what they want to get out of it. One nice thing about not teaching in a university is that I don't have to grade students or tell them what I think they should do. I can ask what they want to do, and then tell them what to do to achieve that.

Aebersold: There are a lot of people who have tried to improvise, and they can't do it the first time so they quit. But what do you succeed at the first time you try? It's ridiculous to even think that. I think it goes back to that feeling that you either have it or you don't.

I think all humans, inside, want to be part of music. I think they know instinctively that they want to play or sing what's inside their head. But they haven't had the training so they don't know how to get it out. But this fear thing... I read an article that said the reason a lot of people don't sing is that when they were kids, they were singing "Happy Birthday" and somebody, probably jokingly, told them that they couldn't carry a tune in a bucket or gave them a funny look. The person feels traumatized and thinks, "I'm not going to sing in front of anyone again. I'm not good enough."

RM: When Mike and I were in music school together, a common complaint was that the school was too focussed on classical music from the past rather than music of the present, such as jazz. But now, some complain that jazz education is too narrowly focussed on swing and bebop, which was the music of the '40s and '50s, and not enough on what students need in order to go out and work today's gigs.

Tracy: With most of the students we have here, their main need is bebop and swing music. People may think of that as a narrow period of time, but that period gives them the knowledge that lets them evolve into other things.

La Barbera: You can't begin to think of playing fusion unless you have all the fundamentals and background from the '20s to the present.

Sherman: Bellarmine has several fusion ensembles, and one thing that's fun for me to see is people coming to jazz through the back door. Unless you have Jamey Aebersold for your dad, you don't grow up hearing jazz, so most of these people come in with other backgrounds–bluegrass, rock 'n' roll, sometimes classical. They can play in a fusion group, and they realize how much more there is to jazz improvisation, and how much more complex jazz chord progressions, scales and melodic development are. Then they might get more interested in going back to bebop, having come in through the back door in a fusion group.

La Barbera: That's a good point. I meet students who complain because we don't embrace new-age jazz music. Those are the same students who will buy a Bill Evans record, which a lot of new-age stuff is based on, and realize there is a lot more to it and bring themselves back into the history of jazz. Aebersold: The thing I was going to say first was, so what if we have a narrow view in somebody's mind? Bebop is fantastic music and there's nothing to defend. I remember many letters and phone calls I made to WFPL asking what happened to Horace Silver, Cannonball Adderley, Kenny Dorham, Miles Davis, Sonny Rollins? How come you don't play any of their records? After a while I started thinking there was something wrong with me. But I've got a whole houseful of jazz and every book says these are THE people, and what are they playing? Bebop. That's the standard. Sometimes Coltrane will go off and play "Ascension" and Sonny Rollins will venture over here and so forth, but the basis for the whole thing is the knowledge of the scales and chords of this music called bebop. So what's wrong with that? That's your doctor's degree in music as far as I'm concerned. If you can do that, you can learn to play anything else.

La Barbera: Last semester I programmed a lot of contemporary material by a well-known New York City composer/arranger with the big band, and I got a lot of flak from the kids in the band. They want to learn about the music of the past, like Ellington; they didn't want to work on contemporary stuff. Also, I have a big band at Floyd Central High School in Indiana. Those kids want to do old Basie swing stuff, and they're having a ball.

RM: How did the U of L students feel about playing with Randy Brecker last year?

La Barbera: They loved it. See, Randy is known for the Brecker Brothers but he would rather play what he played with our band: straight-ahead bebop jazz. But his record company forces him to put out these funk/fusion albums. His solo album is still sitting in the can. They would not put it out until he put out another Brecker Brothers album.

Fitzgerald: Anybody who complains about the jazz establishment being stuck on any one style has to realize that any teacher is going to have his or her own preferences, and if they're older than you are it's probably going to be something that predates you. Rather than complaining about what they're doing, take it upon yourself to be the one to bring this into jazz education. And when you get to that point, there will be some kid saying, "Why don't you do this?"

That's the way it's always been. I remember going to the Chick Corea Akoustic Band concert and hearing some people in this room say they were less than thrilled, but I thought it was a great concert. Then I heard the Chick Corea Elektric Band concert. People were saying they thought it was great, and I was saying, "Well, that's not really jazz." Then I realized I sounded just like these guys. [laughter] So it's always going to be that way, and there will always be somebody who thinks you're just as stodgy as your teachers were.

RM: Is jazz education still encountering resistance?

Tracy: I don't think there are many, if any, on the faculty now that I have to convince that jazz education is a healthy thing. A couple of years ago, I got to school early one morning and so did [classical pianist and U of L Artist-in-Residence] Lee Luvisi, and we rode the elevator up together. He turned to me and said, "I want to commend you for what's going on here. When I come here in the morning, there is always music coming out of the jazz studios. Somebody is always playing or practicing. You don't hear anything coming out of these other studios. Whatever you're doing, you're doing it right. The students are enjoying what they're learning and they're playing and practicing. That's what we all should be doing."

That the thing about jazz besides the technical aspect: most of us love doing it. You go to hear a jazz band play, the kids are having a good time. Most of them are not required to be there, they get little if no credit towards their degree, but the bands are always filled and they're enjoying it.

Fitzgerald: When I was here, I had some wonderful teachers, but I knew some people who were more afraid to play after their lesson than before their lesson. And after years and years of lessons, it seemed that some people liked to play less than before they took lessons. Whereas with the people in the jazz department here, you'd find groups of four or five people getting together to play for no credit just because that's what we wanted to do. I still come over and play and I graduated years ago. That's one of the most positive things that's come out of this: People who love to play music realize that it's okay to love to play music and we're going to get together and do it. Because that's what jazz is about in the first place. It's not about frightening you into playing a certain way. It's letting you explore things on your own.

pull quotes (could be used beneath individual photos)

Jamey Aebersold: "There are teachers who realize they are not getting through to the students because they don't know how to teach improvisation."

Chris Fitzgerald: "You don't play this music thinking that you're going to make a lot of money_"

John La Barbera: "We are not trying to turn out jazz musicians; we are just one part of the music-education process."

Jeff Sherman: "To play as much jazz as we have in Louisville is really a blessing."

Mike Tracy: "I've played 'Giant Steps' at wedding receptions."

blurb for cover

Jazz Educators Roundtable

After years of struggle to be recognized as a legitimate art form, jazz has now taken its place on many college campuses including U of L and Bellarmine. But what is the true value of improvisation to a complete music education, and can one find happiness playing jazz in Louisville? These questions and more are discussed by local jazz educators Jamey Aebersold, Chris Fitzgerald, John La Barbera, Jeff Sherman and Mike Tracy.