social bookmarking tools:

|

|

| Available RSS Feeds |

|---|

- Top Picks - Top Picks |

- Today's Music - Today's Music |

- Editor's Blog - Editor's Blog

|

- Articles - Articles

|

Add Louisville Music News' RSS Feed to Your Yahoo!

|

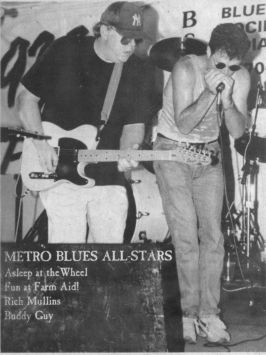

THE METROPOLITAN BLUES ALL-STARS

By Cary Stemle

It's 1983 or'84, no one can remember for sure and the Metropolitan Blues All-Stars are headed west. A couple of years after forming their band in Eastern Kentucky, the longtime friends are ready to take Lake Tahoe by storm.

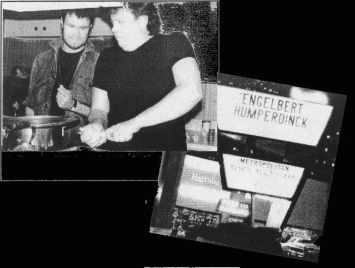

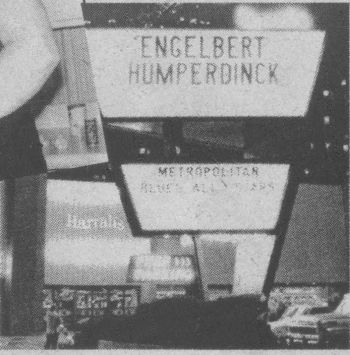

Seems a promoter who claimed ties with Wayne Newton caught their act hereabouts and liked them enough to book them there. The promoter apparently wasn't lying about his connections. There, on the marquee, just below The Smothers Brothers and Engelbert Humperdinck, were the magic words: Metropolitan Blues All-Stars.

"That was one of the first times we thought we were gonna be famous," says the Metros' Nick Stump, ironic emphasis on first. "We thought that was just the tip of the iceberg; we thought we'd be an overnight success. Absolutely nothing came of it."

Well, who's to say? The band may not be a household name but they've carved out a nice little niche for themselves performing their own songs. Critics universally laud them for consummate musical skills. Their records sell well in Germany on the Taxim label, which issues a lot of American blues and blues-rock. They've performed on National Public Radio's "Mountain Stage" a handful of times and been featured on NPR's "All Things Considered."They'll make their fourth or fifth appearance (again, no one quite remembers) at the Kentucky Center for the Arts' Lonesome Pine series on Friday, November 1O, where they'll be joined by David Barrickman on keyboards and Tripp Bratton on percussion. Their previous Lonesome Pine shows have sold out.

In short, they earn their living playing music. Not such a bad gig for some boys from the hills of Eastern Kentucky.

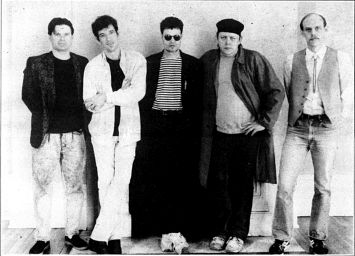

Stump and Rodney Hatfield go back to 1969 and Stump has known guitarist Frank Schaap almost as long, but the band as such began in 1981 when they formed as a trio. They added a rhythm section soon after and the lineup has been intact for more than a decade. David White plays drums and Rick Baldwin is the bassist..

Stump (given name: Michael Stamper) grew up in Hindman in Knott County and Hatfield (yes, he's a descendant) in Blackberry Creek in Pike County. It was the heyday of clear-channel radio and the youngsters were fortunate to cut their teeth on WLAC-AM out of Gallatin, Tennessee, where the nighttime jocks were playing blues by Lightnin' Hopkins, Bobby Blue Bland and Muddy Waters, to name a few.

"It was coming right from the source," Stump says. "It was great. You could mail-order the records direct from Randy's Record Mart, which I think was at the station. My classmates were into the Beatles and I was ordering these records in the mail."

He dug the British Invasion, steeped in blues as it was, but for awhile he thought the native mountain music that was just around the corner was akin to an ice pick through the ear drum. That changed when his dad brought home a Folkways recording of indigenous music of Eastern Kentucky, then carried him to Hazard to hear and meet one of the featured artists one Saturday afternoon on the courthouse steps.

"His name was Roscoe Holcomb and I'll never forget him," Stump says. "He played this odd-tuned banjo and he sounded like Lightnin'. It was the coolest thing. My dad made me do all those old ballads and I hated it. But that made me aware there was more to hillbilly music than nasal singing and banjo pickin'. I realized the Dobro player with Flatt and Scruggs was playing blues and Bill Monroe was doing blues licks on the mandolin."

Hatfield had fewer qualms about the hillbilly music of Hank Williams, Lester Flatt and Earl Scruggs and the Grand Ole Opry. That is, until adolescence set in.

"When I was a kid I dug it, but when you got a little older, there came a time when the last thing you wanted to admit is that you like hillbilly music," he says. "So there was a brief period when I lost appreciation for it."

No more. In fact, eclecticism informs the band's music today. They're a blues band, certainly, but not in a traditional sense. You'll hear Chicago, but also Southern and country blues, rock 'n' roll and strains of that mountain music. All of which, of course, runs the risk of offending traditionalists.

"We sorta sound like blues, but I really think our band stands outside of what you traditionally think a blues band would do," Stump says. "We're basically a bunch of hillbilly musicians who play blues music as it sounds to us. We're not purists. I'm glad there are those people, but when you look at blues, there's a tradition of change. It's evolved, taken in other influences. Look at Muddy after he moved to Chicago. He was playing that big electric guitar and orchestrating his sound. He wasn't some idiot savant, he was looking to entertain. But at the time, the purists were probably alarmed."

In addition to some early cassettes, the band has four albums' out: Life of the Party and Trying Times on June Appal Records, Devil Gets His Due on New Hillbilly and Hillbilly Nation on Loose Canons, the band's own label. Some of their other stuff has been re-issued in Germany. Stump does the basic agenting — "by default" — and their records are distributed by a couple of different companies.

They tour pretty much throughout the year, traveling in a conversion van and going out for 10 or 12 days at a time into Kentucky, Tennessee, Virginia, the Carolinas, Georgia, Alabama and Florida. (Road man Pete Barrows accompanies them on longer trips.) They also do some gigs in Chicago and New York and work individually with other artists. They play occasionally in Louisville, where Stump lives and more often in Lexington, where the other four members reside. (Hatfield also spends a lot of time in Louisville.) They're thankful for local support, but wary of getting comfortable playing here too often.

"If you wanna make a living in this business, you gotta work 'em all," Stump says. "You have to avoid the trap of playing at home all the time. The audience would become contemptuous of the Beatles if they saw them play every night."

Don't take life too serious. It ain't no way permanent.

That's a nice, fuzzy, warm saying, probably profound enough to end up on placards in the kitchens of urbane folks across the land. In fact, one hangs in the kitchen of musician Nick Stump and his wife, Bonnie McCafferty. In the past few years, Stump's walked under it many times. It meant something on some level, but never packed the urgency it did after one of two aneurysms on McCafferty's carotid artery burst. Literally fighting for life, she was in the hospital a month.

Perspective?

Sitting in the kitchen of his home near Louisville's Tyler Park, quaffing coffee, offering a visitor apiece of chess pie from the Hommade Pie and Ice Cream kitchen and managing Kodi, his, um, persistent Akita, Stump addresses the ordeal by pointing to the sign.

"It was up before that happened," he says. "I've looked at it a lot more since."

Of course, Stump was dazed and confused. Angry, actually. One doesn't wait 45 years for a soul mate to watch that person check out. "It was a selfish reaction, really," he says. "It was terrifying. I thought my whole world was gonna be pulled out from under me."

Perspective is a fleeting thing, but the sign helps remind Stump of his healthy dose.

"Something like that gives you some perspective on what's important and what isn't," he says. "At the time, I thought I couldn't bear it. But her recovery at home was probably the sweetest time I'll ever remember."

As for his wife of 3-1/2 years, McCafferty writes for Louisville Magazine and The Chicago Tribune, among others. They say opposites attract and that people shouldn't take up with others like themselves, but Stump says that may not apply to artists.

For one thing, folks doing the 9-to-5 seem to have-a hard time with the concept that being home during the day and playing on nights and weekends- — often away from home — is actually "work." That's not a problem now. The couple share input about each other's projects and they edited one another's books: Stump's The Land of One-Armed Men, a book of about 100 poems and songs and McCafferty's Smiling Through the Apocalypse, a collection of her columns. She designed the cover of the band's latest album, Hillbilly Nation. Other than a difference in sports allegiances (let's just say Stump has spent many months in misery since the Cards nipped the Cats last December), it's a smooth partnership.

"l think it's real good for both of us," he says. "This is an adult relationship and I really like it. I found the one for me. It took me almost 50 years, but that's all tight."

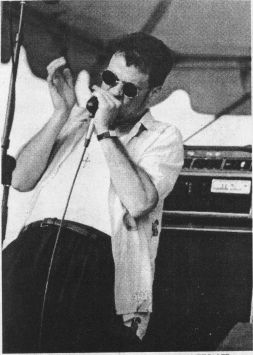

Besides enjoying a stellar reputation as a harmonica player, Hatfield is an accomplished painter. In fact, a lot of people mistakenly think art is an afterthought, but Hatfield says: "I've been painting all my life and I never stopped. My parents never could beat it out of me."

He paints on various media — paper, wood, masonite – and with various paints.

Each opens a different window. "Any time I change media, l think it changes the look and style," he says. "I hope there's a thread that runs through it, but I'm not overly concerned with that. I'm more concerned with the spontaneity of the process."

His work hangs at Swanson Cralle Gallery in Louisville and in galleries in Santa Fe and Cincinnati and he works by appointment at his Lexington studio. A painting of his dog, Buster, is included in Good Dog: A Tribute to Our Canine Companions, which runs through November 30 at Bank One Gallery, 416 W. Jefferson St. in Louisville.

Hatfield's paintings sell well, which tells him he's moving in the right direction, although he professes amazement that some of his talented cohorts have difficulty selling their work.

As an artist, he uses the moniker Art Snake.

"There's about three reasons," he explains. "I tell people there's a little man inside my head named Art Snake. It's also a play on the idiom 'art for art's sake.' Really, I wanted a separate name from the musical identity. It's fun to have separate personalities."

And his harmonica playing? Contrary to one journalist's myth-making instincts, he did not learn to play in the penitentiary.

"We were interviewed by (NPR's) Lynn Neery and I told her, 'Ma'am, I learned to play in prison,'" Hatfield says. "She didn't believe I was just joking."

I walked around all the time playing this harp," he says. "It took over my life, like a drug. It's all I did. I'd go to parties and play the in-out symphony. I thought I was burning it up, but I was emptying out rooms."

Needless to say, he improved. Now he's one of the most highly regarded blowers in the region. He'll join a host of others, including hero Howard Levy and local fave Jim Rosen, for a Harmonic Convergence on Friday, November 3, at the Kentucky Center. The show is also part of the Lonesome Pine series.

Ask the band about its longevity and the answers are almost gushy.

"The most wonderful thing in the world is to play in a band with four of your best friends," Stump says.

"I feel privileged, I really do," Hatfield says. "I used to be in a place in my head where I didn't understand I had a minor gift and people really like what we do. Now I'm at a point where I have a whole lot more appreciation. It's wonderful when you go to a bank to ask for a loan and they ask you what you do for a living and you tell them you play harmonica and paint pictures. I'm very, very fortunate."

They want to be successful — "Most blues bands will be counting heads in the crowd, too," Stump says but they have no inflated ideas about the future. Hatfield is 48 and Stump is 47.

"When you're young, you have stars in your eyes about what might happen," Hatfield says. "After awhile, if you stay in it, you may not make it big but you can become a musician. I've tried to get out of it several times and I can't. It's almost like we don't have any choice. After a while, we realized that's what we do."

Interestingly, they may have something going with music legend Jerry Wexler, who brought the world Aretha Franklin and a host of other great Muscle Shoals artists. Schaap stuck it a copy of HiIlbilly Nation in Wexler' s mailbox on Martha's Vineyard, and Wexler liked it enough to ask for more copies to shop around. It's uncertain how much influence the 83-year–old Wexler commands these days, but his interest is a heck of an affirmation, at the least.

"It's a trip to talk to someone like (Wexler)," Stump says.

"He asked me how we miked the drums. I told him we used three microphones and he said, 'That's the best way.'"

So how long can they last?

"I think we're in it for the duration," Stump says. "At this point, I have no expectations at all. It's like playing the lottery. If you win, great, but if you let it bother you, it will drive you crazy."

Said Hatfield, with an easy laugh: "War made a promise that if we don't hit it big by the time we're 70, we're going to get out of it. You have to draw the line somewhere."